Scientific and biotechnological advances have transformed our capacity to intervene in human life and, with this, the promise of eradicating diseases and eliminating suffering becomes undeniably seductive. Yet, behind this promise lies a problematic terrain in which the encounter between science and dangerous ideological discourses can revive a dark past which is, surprisingly, not so distant. Eugenics, once expressed through laws of forced sterilisation and ideals of “racial purity” sustained by scientific racism, has not disappeared. It has instead been reshaped, finding new spaces in laboratories, consulting rooms, and political rhetoric disguised as patriotism.

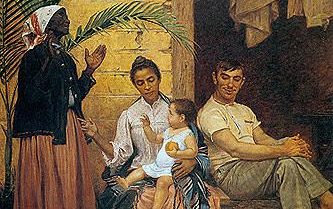

In the early 20th century, forced sterilisation programmes in the United States targeted thousands of people considered “undesirable”: the poor, immigrants, people with disabilities, and Black women. Brazil too had its echoes of “racial purification”, where intellectuals and social hygiene policies, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s, endorsed population “whitening” and reproductive control as solutions to the country’s supposed backwardness.

The Science of “Perfection” and the Ethical Challenge

Medicine offers us the possibility of correcting genetic faults, but the line between cure and elimination becomes tenuous when dealing with conditions that are not diseases, but variations of human existence. The argument of avoiding suffering is powerful and carries immense responsibility, but it forces us to ask: is the “problem” located in disabled people themselves, or in society’s lack of accessibility and inclusion?

At the core of this debate lies the social model of disability. This sociological approach, pioneered by Michael Oliver, argues that disability is a social construction, not a biological flaw of the individual. Why not invest in technologies and infrastructures that would allow people with such conditions to live full lives, instead of focusing on the eradication of their very genes? The technology exists. We do, indeed, have the capacity to mitigate many adversities – but the decision not to do so is, in many cases, political and social, rather than scientific. Parallel to this, we witness the advancement of productive and frontier technologies, while the working hours of the non-dominant classes remain exhausting. The central issue here lies within capitalist forces and their relentless pursuit of profit and domination.

The danger deepens with CRISPR technology, which enables the editing of DNA with surgical precision and opens the door to infinite possibilities, but also to unprecedented dilemmas. Who decides what counts as a “bad gene” or a genetic fault? Science, without proper ethical oversight, risks falling into the abyss of a modern eugenics tied to political discourses.

The Aesthetics of “Purity” and the Dog Whistle in Political Discourse

Alongside medical advances, the rhetoric of “genetic superiority” resurfaces, though now in new guises. Neo-Nazism and racial supremacy discourses, which should have been buried with the end of the Second World War, have gained traction amidst the rise of the far-right. Instead of flags bearing swastikas, the message today is subtler, conveyed through what we call a “dog whistle”.

A dog whistle is an encoded message which seems innocuous to the general public but carries a specific political meaning for a targeted group. The recent American Eagle campaign featuring actress Sydney Sweeney provides a striking example of this type of message. The campaign generated controversy, with specialists labelling it “embedded with eugenics” due to the choice of actress – a white, blonde, blue-eyed woman. The Republican reaction of “can’t you be blonde and beautiful anymore?” is precisely what dog-whistle rhetoric aims at: diverting criticism into a superficial debate about beauty, while the ideological message strengthens its foothold within the base and spreads throughout society.

For the white supremacist, the actress’s image represents beauty tied to the validation of a “good” and “pure” genetic ideal. Moreover, Sydney Sweeney’s affiliation with Donald Trump’s Republican Party provides context about her political positioning on certain issues, drawing the attention of far-right leaders in the United States. Prior to this advertisement, Donald Trump himself had declared in an interview that immigrants commit crimes because “it’s in their genes” – a direct statement evoking the logic of scientific racism in its purest form. In this context, the American Eagle controversy, despite its negative tone, boosted the company’s stock by 10%, adding around US$200 million to its value – a figure that starkly reveals how eugenic discourse can be profitable when linked to extremist groups.

Class Eugenics and the Environmental Discourse

Além da ciência e da estética, a eugenia encontra um terreno fértil na própria estrutura de classes. A pressão econômica sobre a classe trabalhadora, com jornadas exaustivas e salários que não refletem sua produtividade, torna a maternidade e a paternidade uma decisão extremamente custosa. Essa realidade força muitos casais a optar por não ter filhos, submetendo-os a procedimentos e medicamentos anticoncepcionais. É uma “escolha” induzida pela lógica do capital, que dificulta a reprodução da classe trabalhadora, negando a possibilidade destas pessoas deixarem descendentes.

A lógica neoliberal de individualização da culpa (a responsabilidade individual pela fertilidade) desvia a atenção das falhas sistêmicas do capitalismo, como a exploração da mão de obra e a desigualdade de renda. Ao mesmo tempo, essa mesma sociedade é condicionada a endeusar bilionários como Elon Musk, que ostenta mais de dez herdeiros. O contraste expõe uma forma silenciosa de eugenia, em uma seleção baseada em renda, onde a reprodução é incentivada para os mais ricos, enquanto é desestimulada para os mais pobres.

O discurso eugenista se manifesta aqui também através da ideia de que o “mal do planeta são os homens” e “só o fim da humanidade melhorará a natureza”. Esse argumento, que se utiliza de uma leitura rasa da realidade, desresponsabiliza o sistema capitalista e os bilionários, que emitem a maior fração dos poluentes para o lucro. A culpa, convenientemente, é atribuída a indivíduos comuns, e não aos verdadeiros culpados, que são os detentores dos meios de produção nas grandes indústrias e big-techs.

Os discursos aqui apresentados compartilham uma lógica de seleção, eliminação e busca por um ideal. Em vez de apenas perseguir um ideal próprio, a ciência acaba muitas vezes convertida em instrumento, servindo à política na construção de identidades e à economia na imposição de ideais de produtividade. A linha que divide esses mundos é tênue e cada vez mais difícil de ser vista, e é dentro desses espectros que a tecnologia que pode ser usada para reforçar preconceitos raciais, estéticos e de classe, se não houver forças que se entrem em contraposição às ideias que ressurgem.

Where Do We Draw the Line?

We are at a crucial moment in history where genetic technology offers immense potential for exponential progress, while simultaneously opening space for extremism and violations of human rights. The central issue is not whether or not science should be used, but rather how we ensure it remains accessible to all, and not merely in service of an illogical ideal imposed by dangerous ideologies.

Therefore, vigilance against the resurgence of eugenics cannot be confined to a single field: it requires questioning medical discourses that render disability invisible, political rhetoric that employs subtle symbols to propagate supremacy, and economic logics that transform reproduction into a privilege.

It is worth asking: to what extent will we allow such ideologies to become normalised within society, and how long will individuals who reinforce eugenic ideals continue to be elected to high office or platformed in the media? Confronting this reality demands challenging the structures of power that naturalise social and biological hierarchies, and advocating for policies that translate bioethical commitment into concrete practice. Facing eugenics requires more than scientific regulation – it also necessitates questioning the political and economic foundations that sustain it.

References

OLIVER, Michael. The Politics of Disablement: A Sociological Approach. 1st ed. London: Macmillan Education, 1990. 152 p. (Critical Texts in Social Work and the Welfare State). DOI: 10.1007/978-1-349-20895-1. ISBN 978-1-349-20895-1.

https://www.politico.com/news/2024/10/07/trump-immigrants-crime-00182702

https://g1.globo.com/saude/noticia/2025/08/19/edicao-genetica-da-sindrome-de-down-levanta-questoes-controversas-sobre-eugenia-e-etica.ghtml

https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/entretenimento/filiacao-politica-de-sydney-sweeney-e-revelada-apos-polemica-em-anuncio/

https://g1.globo.com/ciencia/noticia/2022/03/20/entenda-o-que-e-o-crispr-ferramenta-que-consegue-editar-o-dna.ghtml