The trial of the attempted coup in Brazil by forces loyal to Jair Bolsonaro’s government in the Supreme Court represents a unique moment in Brazilian history and carries a weight similar to that which exposed Nazi barbarism 80 years ago.

Since 2 September, Brazil has been following the long-awaited final chapter in the coup saga led by Brazilian far-right leader Jair Bolsonaro. This is the culmination of two years of investigations that revealed a complex and well-orchestrated plan to abolish Brazil’s democratic rule of law, replacing it with a regime of exception led by then-President Jair Messias Bolsonaro.

Without revealing anything new about Bolsonaro’s coup attempts, who has a history of defending the military dictatorship, torture methods, the execution of thousands of people and contempt for liberal democracy, evidence from investigations conducted by the Brazilian Federal Police revealed that all the coup rhetoric went far beyond simple ‘political rhetoric’ (as many Bolsonaro supporters and defenders have tried to sell for years)1.

After losing the 2022 presidential election, Bolsonaro spent the three months following the release of the results conspiring with his closest allies and high-ranking military officials to subvert public order, assassinate the president-elect, his vice-president, and Supreme Court ministers, and remain in power. Similar to the lie told at the time of the 1964 coup, some evidence shows that there were plans to hold ‘new elections in the future’ (last time, the hiatus was 21 years).

The facts revealed by the Federal Police are shocking. Contrary to what the word might suggest, the attempt did not remain in the preliminary stages of ‘discussing ideas.’ The bloodiest part, the assassination of authorities, was almost carried out, with Bolsonaro’s agents positioned in strategic locations to commit the murders2. Due to a combination of variables beyond the political (and factual) scope, the authorities were not executed on the night of 15 December 2022, after the ‘mission’ was cancelled at the last minute3.

A week earlier, Bolsonaro had attempted to co-opt the heads of the military forces for his coup. Two refused, even under pressure from colleagues4. However, these two generals did not ‘save’ Brazilian democracy. In fact, they failed in their duty, first and foremost as citizens, to immediately report that there was a concrete plan to disrupt the Brazilian democratic regime.

Without sufficient support from the military, a plan B was put into action. This part was seen around the world on 8 January 2023, after the inauguration of President-elect Luís Inácio Lula da Silva. Bolsonaro had fled to the United States (at the time under the Biden administration, which was openly opposed to the coup in Brazil5). Thousands of Bolsonaro supporters, under the protection of military forces, attacked the headquarters of the three branches of government in the federal capital. The destruction of the headquarters of the executive, judiciary and (to a lesser extent) the legislature, however, was not the coup itself.

With chaos reigning in Brasilia, it was suggested that a so-called ‘GLO’ (Guarantee of Law and Order) decree be issued. This measure gives the military, for a limited time and scope, police powers in order to restore order. At that moment, the First Lady advised Lula not to enact this mechanism6. Even though it would not put the military in power, granting such authority to the military within the federal capital in the first eight days of government (a military that a month earlier had been meeting with the former president to enact a coup d’état and assassinate, among others, Lula himself) did not seem a desirable option. That night, after being expelled from public buildings (very late, it should be said), the coup supporters could not be arrested by the police because the Army prevented the police from arresting the Bolsonaro supporters (who were camped in front of barracks in Brasilia)7.

As a result, the coup was ultimately prevented. The following day, Lula met with the leaders of the other two branches of government and marched in Praça dos Três Poderes (Three Powers Square) as a sign of support for democracy. This was despite the fact that leaders of the legislature (both at the time and today) were closer to the coup plotters than to the effective defence of democracy.

It took months of investigation before the public finally learned the details of what had been orchestrated (and executed) in the months before the current president took office. In the meantime, some conspirators have already been arrested, while others have begun to try to absolve themselves of guilt.

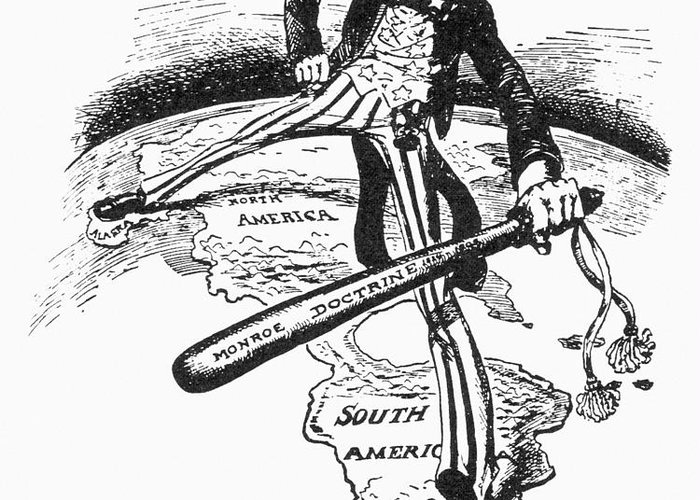

The centre of the coup, however, remained strong. Bolsonaro, who later returned to Brazil, as evidence shows, allegedly planned to flee twice by requesting political asylum in Hungary (also ruled by an autocrat) and Argentina (which has a leader of similar bias)8, 9. One of Bolsonaro’s sons went into self-imposed exile in the United States (now under the nascent Trump regime), from where he conspires with senior US government officials to put pressure on Brazil. The result of this operation is not only the obscene imposition of 50% tariffs on Brazilian products, but also sanctions against ministers of the Brazilian Supreme Court10. On Tuesday (9), the government spokesperson in Washington went so far as to threaten Brazil, stating that Trump ‘is not afraid to use economic or military means to protect freedom of expression around the world’ in the context of Bolsonaro’s trial11.

Unlike the democratic stance adopted by the Biden administration in the past, reaffirming that the United States would support Brazilian democracy, the Trump administration sees, in the words of its own spokesperson, intervention in Brazilian politics as a priority in order to safeguard US interests.

Finally, we have arrived at the title of this column. Exactly eighty years ago, in 1945, World War II ended after six years of conflict. In Europe, the Nazis’ surrender to the Allied forces did not mean the end of hostilities on the continent. Nazism left a scar in every corner it touched, through its horrendous crimes against humanity. Until recently, there was a global consensus that its deeds and ideology were abominable. Unfortunately, global politics in the 2020s no longer reflects this humanistic thinking.

With so many horrors perpetrated by the Nazis, it was decided at the end of 1945 that a tribunal would be set up to try those who were at the head of the regime. Thus, it was formed in the German city of Nuremberg. Ten years earlier, the city had been the scene of the annual Nazi party rally, where the so-called ‘Nuremberg Laws’ were introduced. These were a set of anti-Semitic laws that imposed, in practice, the dehumanisation of people of Jewish faith and different ethnicities in Nazi society. In this same place, several Nazi leaders (who were still alive and had not fled) were placed in the dock to answer for their crimes, in what became known to many as the birth of International Criminal Law.

In addition to punishing the Nazis in a civilised manner, through a court of law, the purpose of the Nuremberg Trials was also to present to the world the horrors perpetrated by Nazism. That moment should serve as an example to anyone, anywhere in the world, that those atrocities were inhumane and should never be repeated. Nuremberg thus has a much greater historical and symbolic weight than the specific events that took place during those days of trial.

It is interesting to note one aspect of the collection and presentation of evidence by the complainants. The focus of the evidence was placed almost entirely on documents that survived the Nazis’ attempt to conceal their actions (maps, documents, photos, etc.). Victims’ accounts, however appealing they might have been to public opinion, were avoided, as it was believed that such evidence could be considered ‘subjective’ and thus weaken the prosecution’s case. There were 111,000 documents, 4,600 pieces of evidence, 30 km of film and 25,000 photographs. Even though they all pleaded not guilty, the Nazi leaders were found guilty amid the irrefutable evidence presented by the US, French, British and Soviet prosecutors.

The history of Brazil as an independent country is a history of a succession of coups.

After declaring independence on 7 September 1822, Brazil, unlike its Latin American neighbours, became a constitutional monarchy. The idea was that Brazil would not be governed by the interests of one person, but by the ‘people of Brazil.’ The following year, Emperor Dom Pedro I convened a Constituent Assembly that, according to him, should write a constitution that was ‘worthy of him’ (the emperor, not the people). When the constituents attempted to diminish the emperor’s power, the first coup took place. The army was called in to arrest the constituents in the early hours of 12 November 1823. The following year, the emperor himself created a constitution and imposed it.

Far from being a democracy in the modern sense, the monarchical regime allowed the elite to participate by voting for the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies (for those who had the equivalent of approximately £25,000 in assets today). At the end of that century, another coup would take place.

The declaration of the Brazilian Republic came about through a military coup, supported by the elites, which deposed Emperor Dom Pedro II and imposed a republican regime on the country. The people, as mentioned by several historical sources, were stunned by the change of regime (largely because they were sympathetic to the emperor). From that moment on, the relationship between the economic elites and the military forces would be the driving force behind the next coups in the country.

The Old Republic (1889-1930) was democratic in theory, but in practice it was completely controlled by the economic elites. This was the era of coronelismo (from the word “Colonel”) and the so-called ‘café com leite’ (coffee with milk) policy, whereby the elites of São Paulo (coffee producers) and Minas Gerais (milk producers) took turns in power. The end of this republic came with another civil-military coup. With the end of the café com leite consensus, Getúlio Vargas, with the support of the army, staged a coup d’état and took over the government. Four years later, Vargas was indirectly elected under a new constitution (which was democratic in theory, even allowing women to vote for the first time). In 1937, at the end of his term, Vargas staged another coup and perpetuated himself in power, initiating the dictatorship of the ‘New State’. At the time, his excuse was that the communists were trying to stage a coup in Brazil. With the end of World War II in 1945, Getúlio suffered a coup by the military and was removed from power for the first time.

This was followed by a period of almost 20 years of real democracy, with parties on the left and right. It was so open that even former dictator Getúlio participated (and was elected!). However, ‘the spectre of communism’ once again haunted the minds of Brazil’s economic elites, who once again supported the military in staging a coup. This was the beginning of the 21-year military dictatorship in 1964.

After arresting, torturing, killing and ‘disappearing’ several people who opposed the dictatorial regime, including children, economic difficulties caused the “popularity” of the military dictators to decline among the elites, which pressured them to ‘give back’ democracy to the people. Naturally, at this point, Brazilian civil society was no longer the same as it had been during the years of the Old Republic and was exerting pressure through large popular protests (such as ‘Diretas Já’, in favour of the return of democracy and the “direct vote”). The international scenario also contributed, especially with the change of government in the United States, which was no longer as sympathetic to the dictatorships that it had helped to establish in South America.

Since 1988, then, we have had a new republic in Brazil. One that is, in fact, democratic and liberal. It took thirty years for the military to return, once again with the help of economic elites, to try to destroy Brazilian democracy.

At no point in Brazil’s more than 200 years of independence has a coup leader ever been tried in court. Dom Pedro I returned to Portugal to become king there. Marechal Deodoro da Fonseca, the general who led the coup that established the republic, became the first president of the Old Republic. Getúlio remained in power, was deposed, returned to office, and only left again (as he had promised) when he died. The military officers who deposed Getúlio were never arrested. Not only that, but the Army attempted another coup in 1955, preventing President-elect Juscelino Kubitschek from taking office. With the coup having failed, Kubitschek granted amnesty to the coup plotters in order to ‘pacify the country’12. Nine years later, they returned and seized power for 21 years, claiming the lives of hundreds and destroying the peace of thousands. None of these men were tried for their inhumane tactics of torture. On the contrary, they were granted amnesty and continued to worship their ‘heroic democratic tale’ in the barracks, brewing coup sentiment for three decades until they attempted to seize power again with Bolsonaro.

For the first time in 200 years of coups, coup plotters are facing justice in Brazil. However, consensus on the fairness of this trial is far from assured. Less than 50% of the Brazilian population believes that a conviction of Bolsonaro would be fair. Almost 40% say it would be unfair for him to be convicted13. A recent survey found that around 21% of Brazilians do not believe in democracy. And even among the vast majority who do believe in it, 71% say they are dissatisfied with the way it has been exercised14. It is worth remembering that even after years of coup rhetoric and disregard for human life during the pandemic, Bolsonaro still received more than 58 million votes in the second round.

Last Sunday, Brazil’s Independence Day, for the first time, people were seen marching with the United States flag in São Paulo, in a protest in defence of Bolsonaro. People who, according to themselves, are patriots and ‘defend Brazil’.

There are those who believe that the trial of Bolsonaro and the other coup plotters is just a façade. That the outcome is already a foregone conclusion, because the ministers are conspiring against Bolsonaro personally. However, just as the horrors of 1945 were clear to both those who lived through them and those who were presented with the evidence, the guilt of the crimes attributed to the new coup plotters is crystal clear. The evidence is overwhelming and shows not only the intention but also the beginning of the execution of the coup.

The trial, which began on 2 September, is expected to run until the end of this week (12), but for over a month there has been talk in the National Congress of approving an amnesty for the coup plotters. As in the past, there are forces (many of them also from the far right) in Congress that do not want to see the people who set out to steal Brazilian democracy once again facing justice for the crimes they committed. The relativism of the coup plotters’ actions ranges from total denial to acceptance that everything did in fact happen, but that it would be necessary to ‘forget everything’ and move on.

The symbolic significance of Nuremberg for the end of Nazi Germany is, proportionally speaking, the same as the trial of the coup in the Brazilian Supreme Court represents for the Brazilian democratic regime. And that does not mean that they represent a happy ending to the story. Quite the contrary. As stated, Nazi barbarism did not dissipate with Hitler’s suicide, nor even with the trial of the other Nazis. However, it was forcibly curbed to the point that it only re-emerged with force 80 years later. In Brazil, where it is customary to ‘forget and look ahead,’ we do not have so many decades between one coup and another. This time, however, some truly republican institutions seem strong enough to put an end to it and set an example. It is in this light that this week’s independence trial should be considered.

Above all, this trial, like that of Nuremberg, is a public exposé of the coup plotters’ intentions, explored in detail. It is an example for Brazilian history, which can only strengthen it, empowering future Brazilian democrats to fight for the country’s democratic regime and, at the same time, thwarting new attempts to rob the Brazilian people of their freedom.

Bolsonarism will not disappear with a possible conviction of Bolsonaro and his allies next Friday. Far from it. But this is an essential step for Brazilian democracy to show itself to be strong and resilient, setting a unique example in our country’s two-century history.

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=21lQ84pnuwo

7 https://veja.abril.com.br/brasil/coronel-da-pm-diz-que-exercito-dificultou-prisao-de-golpistas

9 https://noticias.uol.com.br/politica/ultimas-noticias/2025/08/21/bolsonaro-asilo-milei-hungria.htm

10 https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/articles/c8rymrp7817o

14 https://www.uff.br/29-04-2025/pesquisa-da-uff-revela-que-79-dos-brasileiros-acreditam-na-democracia