It was an early Friday in Vienna. The autumn chill was slowly making its presence felt, and with a hot coffee in hand, I waited for the train that would take me to Budapest, crossing the border between Austria and Hungary. I would have loved to be going for leisure—Budapest is beautiful—but this trip would perhaps be even more interesting: I would have the chance to attend a lecture by Professor Milan Svolik, possibly one of the greatest names in the study of dictatorships and autocratization in the world.

After two and a half hours of travel to Budapest, and another half hour to the city center, I finally arrived at the former campus of my university, the Central European University, forced into exile in Vienna by Viktor Orban’s authoritarian regime. It’s strange to see such architectural beauty while simultaneously feeling such melancholy for the strong symbols on that campus of a more democratic time. I climbed the beautiful stairs to the Institute for Democracy and finally came upon a small group of people laughing and discussing the day’s news. Among them was another major figure in the field, Professor Andreas Schedler.

Soon Svolik arrived, and the lecture began. And it was in this unassuming, calm way that many of my beliefs about education, democratic competence, the role of institutions, and the democratic history of Latin America were irreversibly shattered. In the interactions between Milan and Andreas, I could glimpse—with some terror—that reality was even more absurd than I had imagined. This column is about the reflections that so astonished me, about the role of the electorate in the democratic crisis, but also about what can be done. It is about terror, but also, I hope, about hope.

Let’s start with the terror. The hope, I hope, comes later.

The Terror

Professor Svolik’s work expanded on many of his previous studies on voter behavior regarding democracy. It was a robust research, spanning decades of collecting and interpreting data from the United States, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Israel, Brazil, Mexico, and many, many other countries. The study had an apparently simple question: what is the price of democracy?

More specifically, Svolik and his many co-authors over the years sought to understand the extent to which voters are willing to trade democracy for policies they prefer. In other words: how many and which appealing policies does a politician need to offer for people to tolerate the weakening of democracy.

Svolik told us he expected to find a large difference between countries, but to his surprise, the difference within each country was much greater than the difference between countries. More specifically, Svolik discovered something shocking.

First, he found that voters who identified as “more right-wing” had a strong tendency to value democracy little, and therefore the minimum required to trade it for preferred policies was much lower than that of “more left-wing” voters. The difference between the two groups was not marginal or negligible, but an abyssal, substantial difference.

This is not to say that left-wing voters would never give up democracy for their preferred policies, but that they would need the promise of several preferred policies before doing so. The difference lies in degree. Right-wing voters seem comfortable giving up democracy for very little.

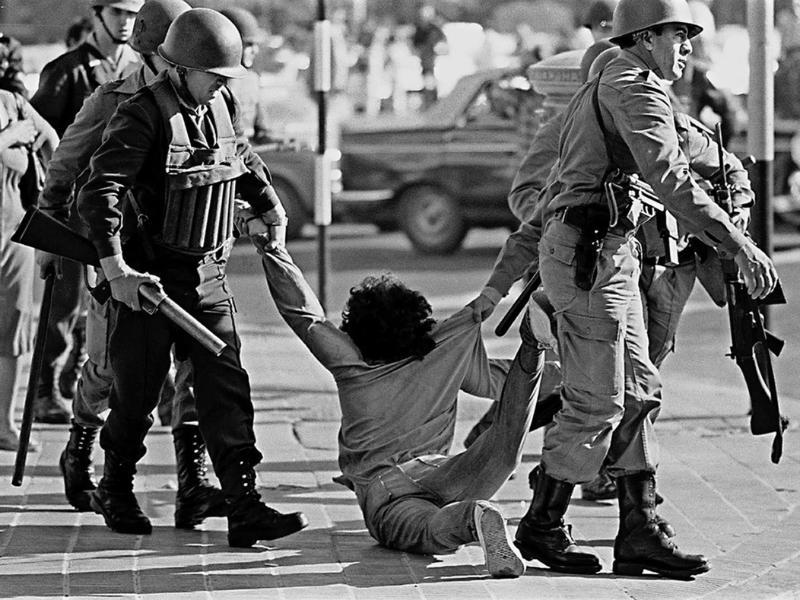

For example, a candidate who targets judges in their country and international NGOs could be elected by right-wing voters as long as she privatizes a few unprofitable companies. Or a candidate advocating the return of a historical dictatorship could be elected by right-wing voters if she also promised to properly pave the country’s streets.

This may seem surprising in the Latin American context, which has historically seen the rise of several left-wing dictatorships. One might expect, following historical trends, that Latin America’s left-wing voters would be just as easily “purchasable” as right-wing voters, if not more so. However, the data points to another reality.

It is likely that the little affection right-wing voters have for democracy in Latin America is actually a reflection of a global phenomenon, not an isolated regional event, as the trend appears everywhere Professor Svolik analyzed. Autocrats learn from one another, and it is likely that this diffusion of narratives and strategies among right-wing leaders worldwide explains this global phenomenon.

Second, Svolik found that this choice of preferred policies over democracy is a conscious choice. About 60% of respondents understood the meaning of democracy, how it works, and its importance. This means that right-wing voters know what democracy is—they just prefer something else.

If you, the reader, are as shocked as I was, allow me to share a bit more about the role of education in the autocratization of countries, and how we tend to overestimate its influence for the better. Mass education (education for large segments of the population) occurred under non-democratic governments. It began with absolutist Prussia and was developed under oligarchic regimes. When democracy arrived in Europe or Latin America, most children were already enrolled in primary education.

But what does a dictator gain from an educated population? Isn’t it harder to control better-educated people? The short answer is no. As Paglayan and Cantoni show (both studies referenced below), the right curriculum and the proper teaching method can be vital in indoctrinating children. There is no reason for a dictator to worry about a population that believes in the dictatorship, prefers it, and even loves it, or about a population that believes nothing can be done, that politics is, in fact, a cultural, insurmountable problem. Indoctrinated people do not revolt.

There is a second reason, as perverse as the first. According to Bueno de Mesquita, the more educated a population is, the higher its productivity, which means, in authoritarian contexts, more resources for the ruler to maintain power. It is harder to democratize China, which is doing well economically, than Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, for example, because China has sufficient resources to ensure the elite do not revolt against the leader.

Right-wing voters know what democracy is, yet still vote against it. But why? One might think voters would tolerate politicians eroding democracy because of economic crises or external threats. However, Svolik found that for right-wing voters, what really matters is the social agenda. Issues like limiting immigration or reducing minority rights are the ones for which they are most willing to give up democracy. A clear example was Poland: Despite economic growth, the population of Poland still voted for the autocratizing PiS party.

As we discussed in the previous column, “May Resistance Bring You Freedom, Even if It Does Not Bring You Peace,” any institutional solution to autocratization fundamentally depends on the support of the electorate. With a voter base increasingly right-wing, and therefore more anti-democratic, what remains for our already battered democracy?

The Hope

The first form of hope is somewhat controversial, and I understand why. It involves the reformulation of the left, so that it learns from authoritarian victories around the world. It means adopting some of the right’s agendas, such as nationalism, digital populism, and us against them mentality. Opponents would rightly argue that this would merely turn the left into the new right, dilute left-wing values, and make the political game officially lowbrow. They would point to post-PiS Poland, showing how the strategy of “being more right-wing than the right” now prevents the democratic coalition from governing without self-sabotage with each new policy.

A fair response, I believe. A real fear, justified by modern examples.

Still, would Poland’s democratic coalition have beaten PiS in the first place if it had not used the same rhetoric and adopted the same strategies? Better difficulty governing democratically than living under an autocratizing government. The electorate seems to be shifting increasingly to the right, and maintaining the same old strategies and rhetoric will be the left’s defeat, and with it, democracy’s.

After Trump’s tariffs, Lula managed to reclaim Brazilian nationalism under the banner of left-wing anti-Americanism and right-wing national sovereignty. Kallas did something similar in Estonia, adopting an anti-Russian and cosmopolitan nationalism. Nationalism does not need to be ethno-nationalist; it does not need to focus on a people, race, or religion. Democratic nationalism can focus on national symbols, like music, flags, etc. It can focus on pride in institutions, in democracy.

The second hope lies in belief—though now shaken—in the role of education. Not education as it is, but as it could be. In particular, I think of figures we have pushed out of Latin America, like Paulo Freire, and his proposal for critical education that promotes the liberation of the educated both in teaching methods and content.

I also think of the role of civil society, mobilizations, and even public intellectuals. For a while, the left relied on the idea that engaging and debating with extremists gave them legitimacy, and that as a society, we should move past these “basic” debates and “evolve” to debates on how to make democracy even more functional, even better for everyone. This was the period right after the fall of the USSR, and optimism about the democratic victory prevailed. Authors like Fukuyama even proclaimed the end of history, with the irreversible and sovereign victory of democracy.

We did not debate with fascists or populists, and as a consequence, they took over the stages we abandoned, spreading without counterarguments. They began to influence millions while we refused to engage. But this can change. We can reclaim the stages we abandoned and, with patience, refute arguments that seem to us a political and social regression.

In this way, we also partially prevent the social erosion caused by polarization. It is necessary to know when to use tact or argumentative force, and this is learned through practice.

References

Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R. M., & Morrow, J. D. (2003). The logic of political survival. MIT Press.

Cantoni, D., Chen, Y., Yang, D. Y., Yuchtman, N., & Zhang, Y. J. (2017). Curriculum and ideology. Journal of Political Economy, 125(2), 338–392.

Fish, M. Steven (2024) The Power of Liberal Nationalism, Journal of Democracy, Volume 35, Number 4, 20-34.

Molinero Jr., G. R. (2025, 28 de novembro). Que a resistência lhe traga liberdade, ainda que não lhe traga paz. DPolitik.

Paglayan, A. S. (2022). Education or indoctrination? The violent origins of public‑school systems in an era of state‑building. American Political Science Review.

Svolik, M. W. (2020). When polarization trumps civic virtue: Partisan conflict and the subversion of democracy by incumbents. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 15(3), 261–287.

Svolik, M. W., Avramovska, E., Lutz, J., & Milačić, F. (2023). In Europe, democracy erodes from the right. Journal of Democracy, 34(1), 5–20.

Svolik, M. W. (2023). Voting against autocracy. American Political Science Review.