Since the beginning of the Russian invasion, the Ukrainian president has been looking for allies around the world. In addition to the arguments expected of a leader defending his country, Zelenskyy is trying to coerce countries into joining his cause – which could backfire.

571 days ago, or a year and a half, Russia began its general invasion of Ukraine. The invasion comes eight years after the first seizure of Ukrainian territory, in February 2014, when Moscow annexed the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea on the Black Sea – as a result of a dubious referendum. It is a fact that, according to census data from the early 2000s, more than 80% of the inhabitants of southern and eastern Ukraine speak Russian as their mother tongue or in everyday life. It is even more a fact that in 1991, at the time of Ukraine’s declaration of independence from the former Soviet Union, the then Russian president Boris Yeltsin recognised the country’s independence – which would keep the territory belonging to the then Ukrainian Soviet republic within the USSR.

Russian recognition of Ukrainian borders continued in the following years. In 1997, Kyiv and Moscow signed the “Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership between Ukraine and the Russian Federation”, in which both recognised the inviolability of the existing borders, affirmed respect for territorial integrity and reinforced their mutual commitment not to affect each other’s security. It also stipulated that the invasion of each other’s territory and the declaration of war between the two sides were forbidden. In 2003, as president of Russia, Vladimir Putin signed another document with the Ukrainian president of the time: the “Treaty between the Russian Federation and Ukraine on the Russian-Ukrainian State Border”. It reaffirmed the mutual recognition of the sovereignty of the two countries.

In 2014, Russia unilaterally decided to change this understanding. Crimea was annexed and has belonged de facto to Moscow ever since – even though there is no broad international recognition of the issue. In 2022, Putin went further and questioned the very existence of Ukraine as a state and quixotically declared a “denazification” of the neighbouring state, starting a war of aggression that in Putin’s new language is called “Special Operation”. The War in (and not “of”) Ukraine has been going on ever since.

The victim of a classic war of aggression, the Kyiv government has been trying (legitimately) not only to hold on to its territory in order to safeguard the very existence of the Ukrainian state through the military mobilisation of the entire country, but also by seeking support from allies around the world – a position that is not only normal, but expected and has been seen by many countries throughout history. President Volodimir Zelenskyy’s strategy for achieving this support, however, does not seem so conventional.

Weeks before the official declaration of the invasion (Putin has not officially declared “war” on Ukraine), Zelenskyy criticised allies. In January 2022, a month before Russian soldiers crossed the (still) Ukrainian borders, the Ukrainian president accused Washington of hurting his country’s economy by “creating panic about a war”, when the US was warning about the concentration of Russian troops on the border. Zelenskyy claimed that he, as Ukrainian president, had access to “more and deeper information than any other president” and that “destabilisation of the country’s internal situation” was the biggest threat to Ukraine. The statements turned sour faster than many perishable foods.

Kyiv’s criticism of its allies, however, did not stop there. The West – meaning the US, Europe and a handful of rich countries in the global north – responded promptly to the Russian invasion, creating a physical and economic iron curtain against Russia. Physical, because the airspace of several countries has been closed to aircraft leaving Russia (meaning that any Russian plane flying west has to make a huge loop around the world) and because Russian nationals have been prevented from entering several countries (such as the states of the European Union, for example). Economic, because the sanctions launched by these countries were unprecedented, causing several companies to stop doing business with Russia (such as McDonald’s, Coca-Cola and Google) and products could no longer be sold there. The confiscation of Russian assets in Western banks and countries also briefly curbed Moscow’s financing. It is also worth mentioning that the rapid Western mobilisation against Moscow went further, leading to a (also temporary) mass movement in which many people were seen to “cancel” Russia and anything related to it – its nationals, its language, its literature, the scientific contributions of its nationals and its products – something that only bears a resemblance to the denial of Nazism in many countries.

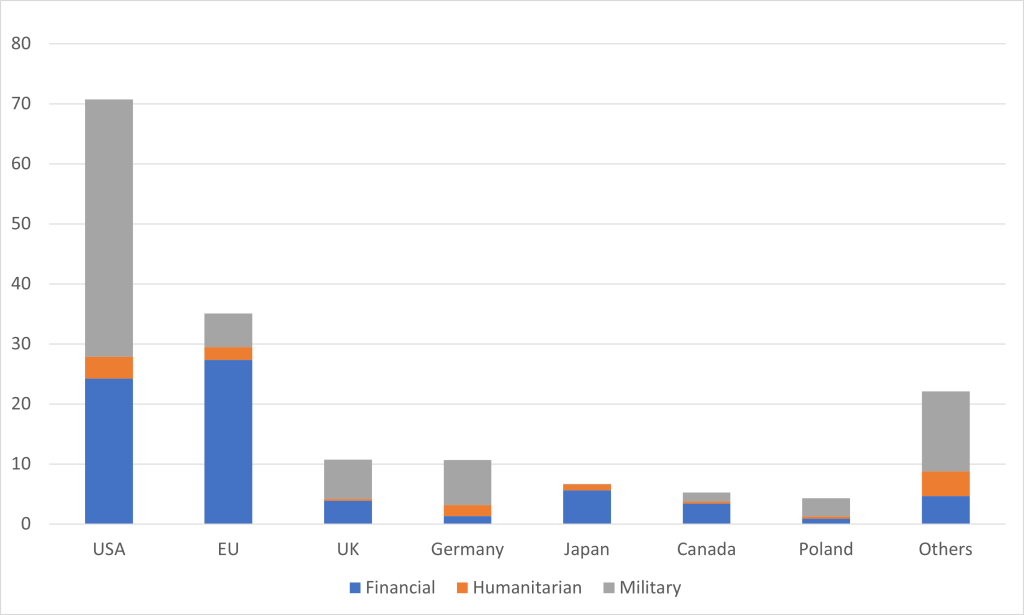

These measures were directly aimed at hurting the Russian economy and creating disincentives for Moscow to continue with the invasion. In order to help Kyiv, the Western allies mobilised military equipment so that Ukraine could defend itself against aggression. The level of ammunition sent almost a year into the war was such that US stocks(!) reached such low levels as to cause alarm in the Pentagon and the country’s Defence Department. All this, however, was not seen as enough by Zelenskyy. The Ukrainian president reiterated several times that the West was “not doing enough” to help Ukraine. Below, the graph shows how much the seven largest donor countries (and the European Union) have sent (in billions of euros) to Ukraine since the beginning of the invasion, divided into financial, humanitarian and military aid. The “other” group includes 31 countries, including from Europe itself (such as Sweden, Spain, Portugal and even Iceland), but also from outside, such as Australia, New Zealand and South Korea. In total, in a year and a half Ukraine has received around 71.3 billion euros in financial resources, 13.7 billion euros in humanitarian resources and 80.3 billion euros in military resources.

Bilateral aid to Ukraine (2022 – present)

in billion euros

Source: Statista

By comparison, in 12 years of civil war in Syria, the country has received around a billion pounds from the UK (or just over 10% of what was sent to Ukraine in one year) and 16 billion dollars from the US (or 21% of the total sent to Ukraine). These figures help to show just how unprecedented the aid sent to Ukraine is.

Diplomacy is a complex art. Saying something while meaning something else. Seemingly “simple” measures, but with important messages. Above all, acting diplomatically involves the careful selection of words when making speeches or negotiating publicly or privately. Zelenskyy did not seem to have a tendency to mince his words before the invasion, and the context of the war seems to have worsened this “quality” of his.

In his criticisms, Zelenskyy is very democratic: he does not moderate his speech with smaller nor larger partners. In April last year, with all the moves made by Western countries and also the European Union, the idea of creating a “jet membership” for Ukraine to become a member of the EU was mooted – a complex process that usually takes years. At the head of the rotating presidency of the European Council – where the Union’s heads of state and government meet – it was Portugal’s turn to receive the Ukrainian’s uncomplimentary words. Even though it had rebuked the Russian invasion, closed its airspace to Russia and sent military equipment to Kyiv, the Ukrainian presidency wanted to embarrass Lisbon, saying that the country expected a more “active” position, given that Portugal was reluctant to accept the unprecedented process of Ukraine’s accelerated entry into the EU.

With Germany, the fourth-largest donor of resources to Ukraine, Zelenskyy alternated between praising and criticising whenever one of his requests was met with some reticence. Berlin (and before reunification, Bonn), which took a long time to re-militarise after the Second World War (and with much reluctance from its European neighbours), took a strong stance right from the start of the invasion in February 2022. Chancellor Olaf Scholz addressed the German parliament, saying that the country was facing a “Turning Point” in its history. The country, heavily dependent on Russia after years of an Eastern European policy developed by then Chancellor Angela Merkel, vehemently condemned the invasion and imposed sanctions on Moscow, even though it severely hurt the German economy. In fact, Germany was one of the countries that suffered most from the blockade of Russia, especially in the run-up to the winter of 2023/24, since most of the gas used by industry and to heat people’s homes came from Russia. The Scholz government, however, did not refuse to support Kyiv both financially and militarily.

Germany’s restraint in sending heavy armaments, tanks and fighter jets was criticised by Zelenskyy. While Berlin was proposing that armaments be sent jointly (with other countries, especially the US) and on the condition that they only be used for defence and not to invade Russian territory, in order to avoid further escalation of the conflict, the Ukrainian president was implying that the deaths of Ukrainians were due to the delay in sending weapons and equipment, blaming Germany – and other countries that were slow to respond to his requests. Zelenskyy went so far as to critically state that Germany only helped “sometimes” and that the German government was “trying to adapt to the situation” (rather than acting in a more “energetic” way), waiting to see “how the situation would develop” internally in the country – in other words, how German citizens would react to the aid being sent. Looking at the situation “from an economic perspective”, according to Zelenskyy, was one of the “many mistakes” Germany made.

Paris was also criticised. Shortly after the invasion began, the Ukrainian president called it “very painful” that Macron had not recognised it as “genocide”. Furthermore, Zelenskyy criticised the fact that Paris was trying to maintain contact with Moscow, saying that Macron was “wasting his time”. The French president, on the other hand, said that he sees no benefit in using a vocabulary of escalation and, as much as he said that Moscow could not win, he refused to defend the idea that Russia “should be crushed”. “That would never be France’s position”, said Macron.

The only restraint shown by Zelenskyy seems to be with his two biggest creditors: the United States and the United Kingdom (responsible for almost 50 per cent of all the money and materials donated to Kyiv). That does not mean, however, that there have not been raids. A month after the invasion began, Biden said that Putin “could not stay in power”, to which Zelenskyy responded with calls for more arms and sanctions from the US, claiming that other world leaders were “timid” about Russia. At the time, he went further, saying that the Ukrainians were not “guinea pigs to be used as experiments” – referring to the “incomplete sanctions” to cripple Moscow financially.

In his crusade to get Ukraine to become a NATO member (in the midst of the war), Zelenskyy has been calling on Alliance leaders to give the country a place, something that is constantly observed with great caution throughout the Alliance. After strong demands at the beginning of the invasion, Zelenskyy said he would tone down his demands as he understood that NATO was “not ready to accept Ukraine”. In fact, according to its treaties, the Alliance cannot accept countries at war. In Zelenskyy’s view, however, the Alliance countries do not want to accept Ukraine because they are “afraid of controversial things and confrontation with Russia”. What’s more, he said that he would not ask to join the Alliance again, because he did not want to be president of “a country asking for something on its knees”.

Two months later, Zelenskyy, virtually invited to attend the NATO summit in June 2022, would demand security guarantees for the country, as it was being done for Finland and Sweden (which eventually began the procedure to join the Alliance in 2022), trying to put pressure on the leaders by questioning whether Ukraine “had not already paid enough”. A year later, when the Alliance reaffirmed that Kyiv could officially apply for membership as soon as it met the prerequisites, Zelenskyy again criticised NATO, claiming it was “absurd” that the Alliance did not provide a “timetable” for when Ukraine could join.

This time, Zelenskyy’s criticism, although directed at the 31 leaders of the Alliance, seems to have struck a chord with Washington and London. Reports in the Washington Post show that the American delegation was “furious” with Zelenskyy’s position. What’s more, sources said that the Americans even considered changing the final declaration of the July 2023 summit, making it “less accommodating to the possibility of speeding up Ukraine’s accession process”. The British reaction came from Ben Wallace, the Defence Minister, who, together with the American National Security Advisor, said that Ukraine should “show more gratitude for the help it has received from the West”. Wallace, for his part, also criticised Zelenskyy, saying that the president habitually treats allies as if they were “Amazon warehouses”, always making request after request for arms without considering the internal politics of his allies. Zelenskyy tried not to put himself down, saying that he did not understand what the minister meant and reiterated his gratitude to his allies.

What you take away from a year and a half of war is that the Ukrainian president does not seem to have much appreciation for classic diplomacy and relies on emotional blackmail and repeated criticism whenever any of his allies – even the most generous ones – do not agree 100 per cent with his requests or rhetoric.

Outside the global north, the war in Ukraine has clear effects that go beyond headlines. Zelenskyy’s reach, however, is not as great as it is in the West. On the one hand, countries outside the global north have not automatically bought into Russia’s “cancellation” policy, no matter how much they have rebuked the invasion in the appropriate forums – such as the United Nations General Assembly.

The Ukrainian president’s harsh attitude towards his allies also appeared with the group of African leaders who sought to organise peace talks between Ukraine and Russia. The delegation of seven African countries, including South Africa, Egypt and Senegal, met with both Zelenskyy and Putin to present a 10-point proposal, which included recognising the sovereignty of both Russia and Ukraine. Zelenskyy’s response to the African peace mission (in particular to a meeting with Putin) was: “it’s their decision, how logical it is, I cannot understand”. The group reaffirmed the position of neutrality of African countries in the conflict, but emphasised that it has negative effects on the continent.

Against this backdrop, it’s no surprise that Zelenskyy’s relations with the new Brazilian president, Lula, have been the way they have been during his first year in office. In fact, the Ukrainian president has not been successful in mobilising his image in Latin America. As recently as June 2022, while he was accustomed to being invited or having his proposals to appear at international events – whether governmental or private – accepted, Zelenskyy had his proposal to speak at the Mercosur summit in Paraguay denied. The justification was that “there was no consensus” on the Ukrainian’s participation. At the time, with Bolsonaro still in power, Brazil claimed to be “neutral” in the conflict.

The Lula government did not claim to remain neutral, as Bolsonaro did. Quite on the contrary, Lula initially wanted to position himself as a possible mediator in the conflict. Several improvised and disastrous speeches, however, put him closer to Moscow’s positions than to those of someone who should be impartial. The Brazilian president is partly to blame for this. However, Zelenskyy would try to repeat with Lula the same “against the wall” policy that he has carried out with European leaders, hoping to achieve good results – which proved to be far from successful. The exchange of barbs via headlines between the two presidents became stronger, with Zelenskyy claiming that he would like to meet with Lula, but doing so by ignoring him whenever possible. The most iconic case was the G7 summit in May this year in Hiroshima, Japan.

Appearing meteorically in Hiroshima, Zelenskyy met with some leaders, but after a confusion of versions – with the Ukrainian delegation claiming that the Brazilian delegation did not have time for them and the Brazilian claiming that it was the Ukrainians who did not want to meet with them – what happened was that Zelenskyy did not show up for a scheduled meeting with Lula, leaving the Brazilian president waiting. Later, when questioned by journalists, Zelenskyy claimed that the Brazilian president was “upset” about the situation – implying that he was not upset about it. After this episode, Zelenskyy continued to criticise the Brazilian president both in newspapers and on social media, hoping that by embarrassing the Brazilian nationally and internationally, he would change his position and start helping Kyiv. In the best example of the Brazilian saying “bite and blow”, Zelenskyy quickly changed tack in July of this year, stating in an interview with Brazilian TV channel GloboNews that Lula would be important for the peace process, helping Ukraine to make its case to the other Latin American countries.

Last week, a few days before Lula’s first speech of his third term at the UN General Assembly in New York, the Brazilian government received a request from Ukraine for a meeting between the two leaders – just as more than 50 other leaders have done. The Ukrainian delegation was promptly offered three times between Monday 18th and Wednesday 20th. After being told that the meeting would depend on “the agenda”, the Brazilian president’s interlocutors told the press that Zelenskyy had agreed to meet Lula in New York next Wednesday afternoon, after Lula’s meeting with Biden.

The war in Ukraine does not seem to give any indication of when it will come to an end. In the meantime, billions of euros in materials and valuables have been sent to Kyiv by allies, despite frequent criticism and disdain on many occasions. Accusations and the use of emotional blackmail have also been rife, which is partly understandable given the injustice of a war of aggression and the brutality of Russia’s policy of denying Ukraine’s very right to exist. However, the prolongation of the conflict with Kyiv’s lack of progress and Moscow’s reluctance has meant that Western allies have grown weary of their patience with the Ukrainian president. What’s more, Kyiv’s often petulant stance with non-aligned countries has also (not surprisingly) not shown positive results in garnering support beyond the West. The world is waiting for new (pseudo-)diplomatic developments with the arrival of winter and the impossibility of mass mobilisations due to the weather in Eastern Europe.

http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/

https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=08000002803fe18a

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60174684

https://www.ft.com/content/a3c943e9-9071-49b8-9f6d-2b82e1f8167b

https://www.ft.com/content/a3c943e9-9071-49b8-9f6d-2b82e1f8167b

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-to-ukraine/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/03/27/ukraine-russia-zelensky-biden-nato/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/07/11/zelensky-nato-ukraine-membership-timeline/

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-65951350

https://www.reuters.com/world/south-african-president-arrives-ukraine-peace-mission-2023-06-16/

https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/06/21/a-failed-african-peace-mission-to-ukraine-and-russia/

https://www.kyivpost.com/post/2193

https://brazilreports.com/lula-at-the-g7-a-failed-visit-with-ukraines-volodymyr-zelensky/4829/

https://g1.globo.com/politica/blog/julia-duailibi/post/2023/09/18/zelensky-reuniao-lula.ghtml