The extraction of lithium to produce rechargeable batteries for cars, smartphones, computers, etc. has become much more important due to the need for an energy transition to reduce the use of fossil fuels. For example, global lithium production has increased approximately 20% per year since 20001, with the Atacama Desert between Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia (Lithium Triangle) representing the largest lithium deposit in the world. However, lithium mining in these areas generate social, economic, environmental, and cultural impacts that cannot be ignored.

The Chilean State in the past years, has been using the control of natural resources (or resource nationalism), in this case lithium, to promote an unfair economic development model, which gave more importance to the extraction and profits of the lithium industry than to the well-being of the communities and indigenous peoples in the region. In this sense, the importance given to lithium extraction in Chile helps to increase injustices in relation to local communities that fight against the expansion of this mining industry.

Resource Nationalism

Resource nationalism is a term used to describe a government’s actions to assert control over its natural resources, particularly those that are considered to be of strategic importance. This can include measures such as increasing state ownership of natural resources, implementing regulations to ensure that resources are used for the benefit of the country, and limiting foreign investment in the resources sector. In Chile, the government has implemented laws and regulations to increase its control over the lithium industry, such as the imposition of taxes and tariffs on lithium exports. These policies are intended to maximize the economic benefits of lithium extraction for Chile, but they can also have negative impacts on local communities and the environment.

John Childs, in his article Geography and resource nationalism: A critical review and reframing, defines resource nationalism as a “tendency for (nation) states to assert economic and political control over natural resources found within its sovereign territory”2. However, this analytical perspective, often, has been influenced by a market-oriented lens3, reducing resource nationalism to just an economic perspective. In this way, resource nationalism cannot be treated from a reductionist or simplified view, this is a complex phenomenon, with social and political implications and the impact of framing resource nationalism as a choice between state or private ownership reduces the scope of the phenomenon to only economic terms and ignores the political aspects of identity and justice4.

Resource nationalism is often seen as an opposition or an “antithesis of economic liberalization”5, which limits the initiative of the international market due to greater control over the exploitation of national natural resources. Using this pro-market perspective and, consequently, of the mining companies, it can be interpreted that this was the case of Chile since as lithium was considered a strategic metal, the Chilean State has controlled it since the 1970s when the dictator Augusto Pinochet was still in power. Thus, the State limited the action of mining companies through bidding processes and extraction quota contracts. However, this does not mean that the State harmed the mining companies’ business, as they continued to profit from the extraction of lithium. This is the danger of using a reductive, pro-market analytical lens. Even with this ‘protectionism’ of natural resources, Chile is the second largest lithium producer in the world6, right after Australia.

Albemarle, the world’s largest lithium producer, has been in the Chilean lithium industry since 1980 when it was granted a concession to mine up to 180,000 tons of lithium per year. Since 2016, with a new agreement to triple its mining quota, its annual lithium production has increased from 22,000 tons to 84,000 tons7. SQM (Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile), the second company allowed to extract lithium in Chile, was founded in 1968 by private investors and the Chilean state. In the 1980s, SQM was privatised and Julio Ponce, Pinochet’s son-in-law, became president of the company. In 1993, the company was granted a license to mine 180,000 tons of lithium per year until 2030. As the second largest lithium producer in the world, SQM produced 120,000 tons of lithium in 20218. Thus, changing the perspective to that of the Chilean State, in addition to guaranteeing the interests of the state, they are achieving a strong participation in the world lithium market. But these strong holdings come at a cost.

Although nationalist demands for resources may seem to arise from national governments, they mask competing claims and identities of a subnational level that does not – or cannot – define itself in terms of resources9. Resource nationalism policies can lead to increased competition and tension between different actors in the lithium industry, including foreign companies, national companies, and local communities. This can result in conflicts over land and resources, which may further marginalize local communities and their rights to participate in decision-making. By allowing ever-increasing mining since the 1980s, the Chilean State is putting at risk the communities that live in the Atacama Desert, which are suffering from water insecurity, mass migration, destruction of local ecosystems, loss of their traditional way of life and violation of their rights. Thus, it is pertinent to understand the context of lithium extraction in Chile to better analyze its impacts.

“We are giving ourselves the luxury of evaporating water in the middle of a desert” 10

Lithium extraction in Chile

Since Chile annexed the Antofagasta region, located in the Atacama Desert, the economy in the region has been geared towards the exploitation of natural resources, such as nitrate in the 19th century, copper in the 20th and 21st centuries, and lithium since the 1980s11. As the production of technologies that support the energy transition increases, global demand for lithium is growing and could exceed one million tons by 2025 and more than 2.5 million tons by 203012. Also known as ‘white gold’, lithium has been mined in Chile since the 1980s after the Pinochet dictatorship classified the metal as state property, and it can only be developed by the state, its own companies, or private companies that work together with the Chilean Production Development Corporation (CORFO)13. The Chilean government has given two companies, SQM and Albemarle, permission to mine lithium in the Atacama Desert and they are allowed to extract almost 2,000 litres of brine per second.

Lithium extraction in Chile, since its beginning, has become an important source of income, investment, and development for the country. The lithium market is worth USD 3.6 billion, and Chile currently has a 19% share, holds 57% of the world’s lithium reserves, and is the second largest lithium producer in the world14.

Lithium can be found in brines, oceans, and rock deposits, and, in Chile, the white gold is extracted by the evaporation of brine from under the salt flats and this is the most water-intensive method of lithium extraction. This is because the miners pump the lithium-containing salt water, called brine, from underground reservoirs into huge ponds for evaporation. Even though it takes months to separate the lithium through the evaporation process, this is still the cheapest method of extracting the metal.

Lithium evaporation pond. Source: Science Photo Library.

However, this technique depletes the Atacama Desert’s already scarce water resources, making the desert even hotter and drier and affecting the marshes, wildlife, and local communities’ access to water. To produce a ton of lithium, it is necessary to evaporate 2 million liters of water from wells and it has been found that excessive extraction of water from the brines can lead to fresh water entering the system to replace the water that was extracted. This affects water sources for human or agricultural use, contributing to water insecurity in Atacama15.

Water is vital for the local communities living in the Atacama Desert, as they depend on it for farming and livestock. Moreover, for the Atacameños, water is not only a means of subsistence, it has is a cultural aspect as well, because the Atacama Desert has been their home for generations. Elena Rivera Cardozo, president of the Comunidad Indígena Colla Comuna de Copiapó, states in the book Salares Andinos that in their culture, the “Pachamama and water are elements of vital importance since they are located in the center of our worldview. We see and feel each other based on a relational bond of permanent contact, they provide us with everything to live (food, medicine, etc.)”16. Due to the uncertain water supply in the Atacama Desert, indigenous communities are forced to migrate in order to survive and sustain their livelihoods. As a result, the 18 indigenous communities in the Atacama Desert have fought against lithium mining in their territories. In this way, the ‘Consejo de Pueblos Atacameños ‘ was formed by local communities to participate in lithium governance in Chile and defend community and environmental rights17. However, this is not the only way that local communities are opposed to lithium mining.

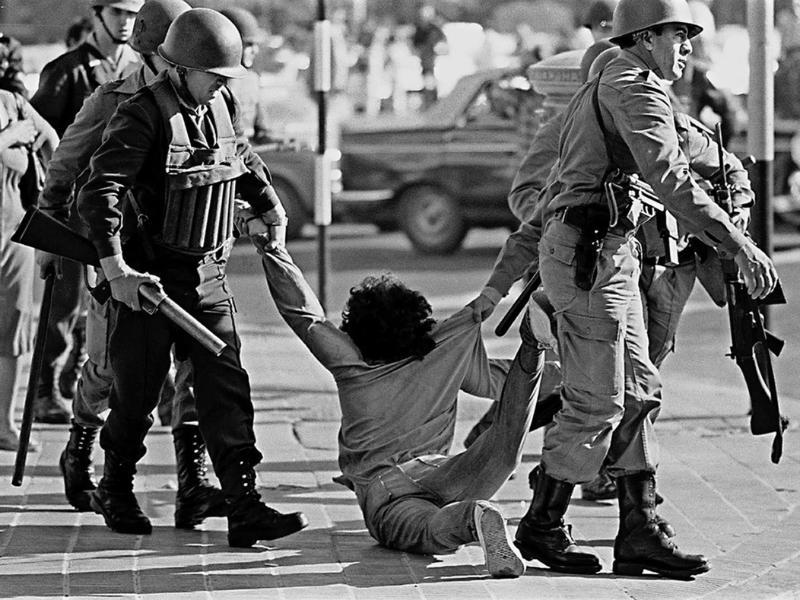

In 2019, synchronized with the biggest anti-neoliberal protests taking place in Chile, the indigenous peoples of the Atacama Desert protested against the intensive use of water for lithium extraction.

Source: NS Energy.

These protests were triggered by secret negotiations between the Chilean State and SQM, in which, the contract that CORFO (the agency for economic development in Chile), signed with SQM gave them permission to increase their lithium extraction by three times in the near future and let them mine in the Atacama until 203018. However, according to the Institute of Latin American Studies19, these protests were repressed by the Chilean State, which declared a state of emergency and quickly arrested the protesters. The State even accused some communities of “water theft”, since, in Chile, almost all water resources are privatized20. This episode can be interpreted as an example of delegitimizing the struggle of indigenous communities. By repressing the protests and accusing the Atacameños of stealing water, the Government puts itself in a position of not validating the indigenous people’s discourse, giving priority to the lithium market and giving less importance to the negative impacts suffered by local communities due to lithium mining.

Another example of the delegitimization of the Atacama indigenous opposition is that according to the Chilean Senate 21, copper and lithium are the reasons why the government can help solve one of the most dramatic problems facing mankind, which is global warming (…)”. Due to this reason, Chile defends the perspective that the extraction of lithium is ‘green mining’. This, however, clashes with the discourse of the Atacama communities, who struggle to protect their lands from the negative impacts caused by mining. Thus, this discourse by the Chilean government in favor of `green mining` can be considered as a form of delegitimizing the struggle of indigenous peoples in the region, since their demands and statements end up being overshadowed by the discourse of energy transition and global warming.

In addition to having their claims delegitimized, it can also be seen that local communities were marginalized. This is because the exploitation of lithium was carried out without the consent of local communities22, this represented a violation of their rights, since, according to ILO 19623, decisions affecting the territory of indigenous peoples require their prior and informed consent. This violation of the rights of indigenous peoples can be considered as a form of marginalization not only because of the violation of rights in itself but also because the local peoples of the Atacama Desert have an ancestral connection with the land they live in, it is part of their culture revere and take care of the ‘Pachamama’. Mining projects cause tensions and can severely affect the relationship of communities to their territory24. According to Elena Rivera Cardozo25, their community continues to practice their ancestral rituals in order to protect the culture that is currently endangered by lithium mining. Thus, by having their consent rights violated, local communities are losing their cultural ties to make room for economic development.

Furthermore, the indigenous peoples are marginalized when the Chilean Government, in its quest for economic development, allows Andean communities to be heavily and negatively impacted for lithium extraction to take place. The main impact of lithium mining in the Atacama Desert is the water crisis, as mentioned above. This water insecurity impacts not only the well-being of communities, but also their economic activity. A study by Sara Larrain26 points out that, in the coming years, there will be a significant increase in mining in the Antofagasta region, causing an increase of 15.6% in water consumption by the mining industry and a predicted decrease of 34.78% in water consumption by the agricultural sector. Thus, the excessive use of water for lithium impacts the water supplies of local communities. This is generating a mass migration from this region, as it is difficult to live in a desert that is becoming increasingly dry27.

Since 2022, with the entry of Gabriel Boric into the presidency of Chile, there has been an effort by the Chilean government to minimize the many impacts caused by mining. Boric intends, for the first time in Chile, to establish royalties on the profits of mining companies. The President intends to continue with the mining industry in the country, being a supplier of renewable energies, but he intends to use the profits of this export model to finance public pension, health, and education programs, with the aim of reducing Chile’s inequalities without aggravating the budget deficit of the country28. In addition, Boric proposes the creation of a state-owned company for the exploitation of lithium “that acts with communities in mind, in the care of the salt flats and in national productive development”29.

Source: Chilean presidency/Ximena Navarro/Handout via Reuters.

This initiative can be considered as a manifestation of resource nationalism since the state is trying to assert control over a natural resource to promote national interests. Since Boric’s government is entering its third year, it remains too early to conclusively assess the impact of these transformative policies.

References

Balcázar, R.M., 2021. Salares Andinos. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Fundación Tanti. p. 22.

Barlow, A., 2022. Piping Away Development: The Material Evolution of Resource Nationalism in Mtwara, Tanzania. Journal of Southern African Studies, pp.1–24. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2022.2028486 [Accessed 05 January. 2023].

Bnamericas, 2022. Spotlight: Chile’s lithium landscape. [online] Bnamericas. Available from: https://www.bnamericas.com/en/features/spotlight-chiles-lithium-landscape [Accessed 3 Dec. 2022].

Boddenberg, S., 2019. Chileans take a stand against lithium mining – DW – 12/04/2019. [online] DW. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/world-in-progress-chileans-take-a-stand-against-lithium-mining/audio-51530175 [Accessed 6 Dec. 2022].

Childs, J., 2016. Geography and resource nationalism: A critical review and reframing. The Extractive Industries and Society [Online], 3(2), pp.539–546. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.02.006. [Accessed 07 January 2023].

Deniau, Y., Herrera, V., Walter, M., 2021. Mapping community resistance to the impacts and discourses of mining for the energy transition in the Americas. (2nd ed.) EJAtlas/MiningWatch Canada. Available from: https://miningwatch.ca/sites/default/files/2022-03-04_report_in_english_ejatlas-mwc.pdf [Accessed 02 December 2022].

Greenfield, N., 2022. Lithium mining is leaving Chile’s indigenous communities high and dry (literally). [online] NRDC. Available from: https://www.nrdc.org/stories/lithium-mining-leaving-chiles-indigenous-communities-high-and-dry-literally [Accessed 10 Dec. 2022].

IELA, 2020. As Devastações da Extração de Lítio no Chile. [online] Instituto de Estudos Latino Americanos. Available from: https://iela.ufsc.br/as-devastacoes-da-extracao-de-litio-no-chile/#:~:text=Os%20povos%20ind%C3%ADgenas%20chilenos%20n%C3%A3o,extrac%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20de%20salmoura%20de%20l%C3%ADtio [Accessed 8 Jan. 2023].

Larrain, Sara. 2012. ‘Conflicts over water in Chile: Between human rights and market rule’, Environmental Justice, 5(2): 82-88.

Lewkowicz, J., 2022. ¿Puede el litio ser producido con un menor impacto ambiental en América Latina?

[online] Dialogo Chino. Available from: https://dialogochino.net/es/actividades-extractivas-es/58865-

puede-el-litio-ser-producido-con-un-menor-impacto-ambiental-en-america-latina/ [Accessed 15 Dec. 2022].

Martin, G., Rentsch, L., Höck, M., & Bertau, M. (2017). Lithium market research–global supply, future demand and price development. Energy Storage Materials, 6, 171-179.

McFarlane, C., and Deneulin, S., 2016. Can our demand for lithium be satisfied without causing environmental and social harm? An inter-disciplinary case study. University of Bath. Unpublished.

Ortiz, J., n.d. Declaración Abierta por los minerales de transición para la COP27. [online] Salares Andinos. Available from: https://salares.org/2022/11/02/declaracion-abierta-por-los-minerales-de-transicion-para-la-cop27/ [Accessed 15 Nov. 2022].

Otis, J., 2022. In Chile’s desert lie vast reserves of lithium – key for electric car batteries. [online] NPR. Available from: https://www.npr.org/2022/09/24/1123564599/chile-lithium-mining-atacama-desert [Accessed 15 Nov. 2022].

Poveda Bonilla, R., 2020. Estudio de caso sobre la gobernanza del litio en Chile [Online]. CEPAL. Available from: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/45683-estudio-caso-la-gobernanza-litio-chile [Accessed 26 November 2022].

Pryke, S., 2017. Explaining Resource Nationalism. Global Policy [Online], 8(4), pp.474–482. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12503 [Accessed 07 Jan. 2023].

Robinson, A., 2022. El Dilema de Boric en Atacama. [online] La Vanguardia. Available from: https://www.lavanguardia.com/internacional/20220206/8037423/dilema-boric-atacama-litio-chile.html [Accessed 15 Jan. 2023].

Selman, C., 2022. Latin American lithium promotion. [online] S&P Global. Available from: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/latin-american-lithium-promotion.html [Accessed 18 Jan. 2023].

Yushuo, Z.H.A.N.G., 2022. Chile to rein in Lithium Mine Exploitation. [online] Yicai Global. Available from: https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/chile-to-rein-in-lithium-mine-exploitation [Accessed 26 Dec. 2022].

- Martin, 2017. ↩︎

- Childs, 2016. ↩︎

- Barlow, 2022, p. 3. ↩︎

- Childs, 2016, p. 540. ↩︎

- Childs, 2016 ↩︎

- Poveda Bonilla, 2020. ↩︎

- Otis, 2022. ↩︎

- Bnamericas, 2022. ↩︎

- Childs, 2016. ↩︎

- Lewkowicz, J., 2022. ↩︎

- McFarlane and Deneulin, 2016. ↩︎

- Yushuo, 2022. ↩︎

- Selman, 2018. ↩︎

- Poveda Bonilla, 2020. ↩︎

- Ortiz, 2022. ↩︎

- Bálcazar, 2021, p. 22. ↩︎

- Poveda Bonilla, 2020. ↩︎

- IELA, 2020. ↩︎

- IELA, 2020. ↩︎

- IELA, 2020. ↩︎

- Deniau and Herrera, 2021, p. 47. ↩︎

- McFarlane and Deneulin, 2016 ↩︎

- Boddenberg, 2019. ↩︎

- Deniau and Herrera, 2021, p. 36. ↩︎

- Bálcazar, 2021, p. 22. ↩︎

- Larrain, 2012. ↩︎

- Larrain, 2012. ↩︎

- Robinson, 2022. ↩︎

- Robinson, 2022, para. 11. ↩︎