After the recent coup attempt, the Lula government, elected to defend Brazilian democracy, prefers a cowardly silence.

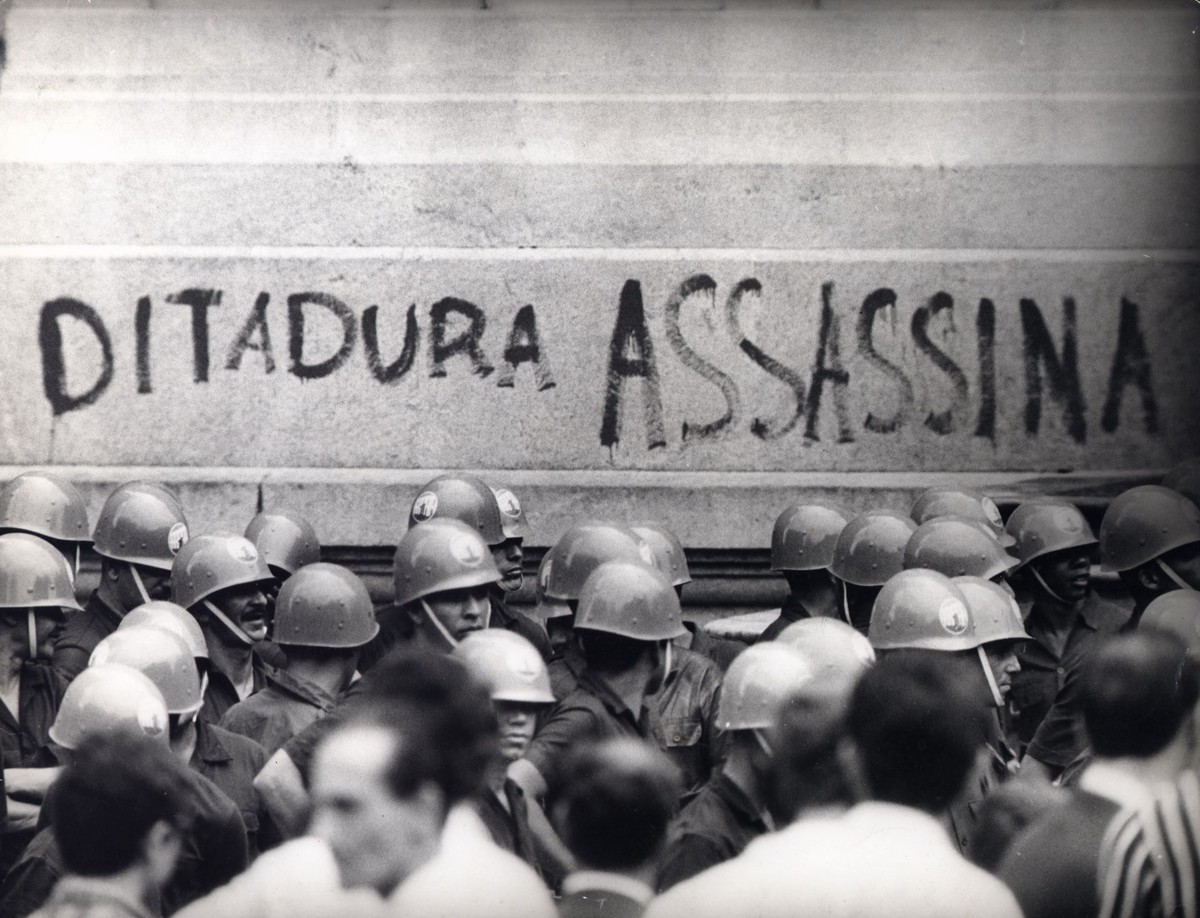

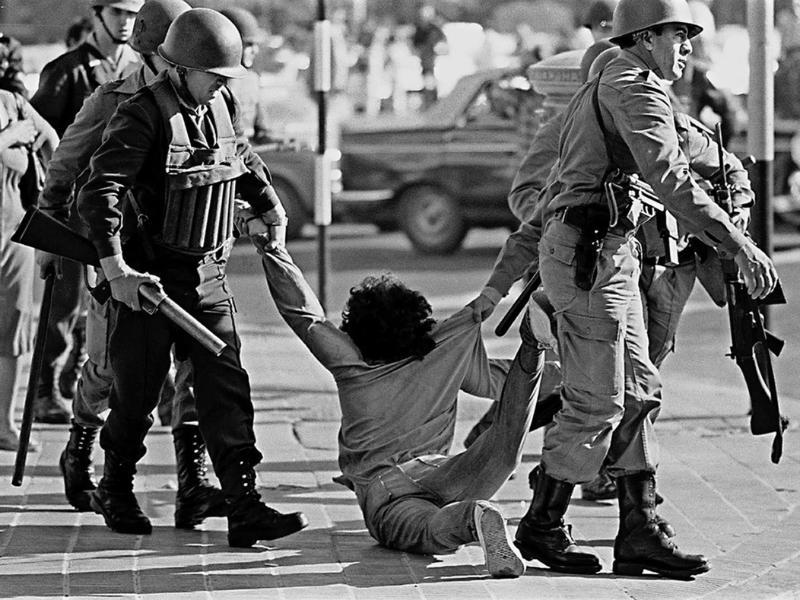

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the 1964 coup that brought an end to the democracy of Brazil’s New Republic, which began with the end of the Getúlio dictatorship in the 1940s. The coup, still celebrated today by parts of society (especially in the barracks) as a “democratic revolution”, led the country into a state of repression of social movements that lasted 21 years. This should not be a date to be forgotten. On the contrary, it needs to be used as a historical reference so that our country remembers that democracy is not a given, nor is it natural.

Unfortunately, the 60th anniversary of the coup has not become any less important in recent years. After a term in office of a president who disdained the liberal-democratic state achieved just over 40 years ago, but who, more importantly, became involved in a plot with part of the armed forces and civil society to carry out another coup so close to this 60th anniversary, it is even more essential that the memory of the 1964 coup be kept alive for what it is: the reversal of the liberal democratic order by replacing it with military authoritarianism.

Among those who defend democracy, a similar stance would not be surprising. What is surprising, however, is the position taken by the current government, which, having been elected under the banner of defending democracy and having experienced an attempted coup d’état, prefers cowardly silence. Just over a year ago, when democratic institutions united after the attacks on the headquarters of the three branches of government in Brasília, there was a perfect moment of national unity that should have been used to make it clear to authoritarian forces, especially in the army, that there is no place for such anti-democratic thinking in the Brazil of the 2020s.

Using a dangerous conciliation, not to use the word coward, President Lula is repeating the policy of appeasement that he had already adopted in his first terms. For Lula, and allies who defend this approach, there is no reason to create “friction” with the military, since this could “stir up” tempers in the country and what we need at the moment is “peace”.

Not recognising and condemning the obvious for fear of angering the military, however, is, on the one hand, a report that something is not right in Brazilian democracy and, on the other, a clear limit to how far we can go in defending the Brazilian democratic state. Of course, the country is polarised in a way it has never been for decades, but the solution to this situation is not non-confrontation with agendas that are essential for common life. After all, the country’s political system is the cornerstone on which Brazilian society must be built (or restored).

Of course, there has already been a “victory”, if we can call it that, for the democratic camp. Since last year, there have been no more commemorations of the coup in barracks1. This year, a similar policy is being repeated, with threats from the current army commander, Ga. Tomás Ribeiro Paiva, to punish anyone who goes against the directive2. In addition, Lula’s order that the celebration of the anniversary of the coup, where what the coup meant would be brought up, also in the context of the attempt at a new coup in 2023, seems to find support among a large section of the population. A recent DataFolha poll showed that 59 per cent of Brazilians would consider the government’s position on banning ministers from holding events on the 60th anniversary of the coup to be correct3. Thus, only a “bubble” of 33 per cent would view the ban critically.

The problem with this, and the data corroborates this assertion, is that the seriousness of a coup d’état is not well established in the minds of Brazilian citizens. This is the logical explanation why many don’t see a problem with not problematising the 1964 coup, nor with punishing those involved in the attempted coup on 6 January 20234.

As much as schools now teach the correct term for the coup and dictatorship, there are many in society who continue to falsely name this period of Brazilian political history “revolution” or “military regime” in order to treat a crime against the country as something heroic. In their quixotic fight against the communist mill, the Brazilian military are still treated by many people, both ordinary and influential, as those who can be trusted and who have an endorsement to “moderate” the Brazilian political system, just like the extinct function of the Emperor of Brazil.

In the Brazilian Republic, the political system must regulate itself through its democratic institutions. These are represented by the three constitutional powers, the Legislative, the Judiciary and the Executive. Neither the army nor any other institution or movement is constitutionally authorised to interfere in the functioning of the Brazilian democratic state.

We cannot allow intruders. The price to pay for ignoring the danger of authoritarianism is the possibility that the past silence imposed by the dictatorship may become today’s “shut up”, gradually corrupting the current democratic system and, with it, the freedom of the Brazilian people.

Sources

1 https://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2023/03/31/forcas-armadas-nao-comemoram-golpe-militar-no-31-de-marco-pela-1a-vez-em-cinco-anos.ghtml

2 https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/colunas/painel/2024/02/comandante-do-exercito-diz-que-nao-havera-ordem-do-dia-nos-quarteis-no-aniversario-do-golpe.shtml

3 https://www.poder360.com.br/brasil/datafolha-59-acham-que-lula-agiu-bem-ao-vetar-atos-sobre-golpe-de-64/

4 https://valor.globo.com/politica/noticia/2024/01/08/para-42percent-punicoes-contra-golpistas-sao-exageradas-diz-pesquisa.ghtml