It is quite common that when thinking about lobbying, the mind inevitably conjures fantasies of a villain with a monocle and tuxedo, smoking a cigar and making shady deals in dark rooms with corrupt political figures. In neopatrimonialist countries like Brazil – a concept that denotes a political and economic organization that blurs the lines between public and private goods and spheres – lobbying has a deeply tarnished history with enough scandals to justify such an image. Even so, lobbying is much more than its scandals, and when used correctly, it can be an extremely important democratic tool.

In essence, interest groups – the professionals responsible for lobbying, also known as advocacy – are organized groups that seek to influence government decisions. By definition, there is no corruption or malevolent intent behind these groups. For example, if the goal is to influence the government to create more social policies, perhaps improve education, boost environmental protection, or increase the number of jobs in the country, the responsible groups would still be lobbying, and it would be lobbying with seemingly noble objectives.

It’s not only by definition that interest groups act against this harmful stereotype. Take, for instance, groups like FERN, Transparency International France, trade unions, corporate policy observatories, human rights advocacy groups, and many others with noble missions that operate in Brazil and abroad. But of course, not everything is rosy. Just as there are interest groups with noble objectives, there are also those that are not as well-intentioned. Examples include the Heritage Foundation, the Heartland Institute, and the MCC.

The Heritage Foundation is the U.S.-based interest group behind Project 2025, a 922-page proposal detailing an ultra-conservative, far-right vision for the U.S., with an executive branch wielding near-absolute powers, replacing career civil servants with loyalist appointees, implementing measures against reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ rights, immigration, and environmental policies. The Heartland Institute operates in the U.S. and the U.K., and is a think tank dedicated to producing and amplifying content that denies anthropogenic global warming – human-made global warming – and positions on public health. Such content is produced and amplified even when it is clearly fake news. Finally, the MCC is a Hungarian think tank that has received over $1.3 billion in state funds from the Hungarian government, led by Viktor Orbán’s political director, Balázs Orbán. In addition to advocating for far-right views and policies in Europe, the think tank also focuses its activities on denying the climate crisis as a whole.

Interest groups operate in various ways, depending on the country’s institutional arrangements. For example, in Finland, interest groups are an official part of the country’s lawmaking process, with official consultations from the government, whereas in the U.K., their status is less formal, without official spaces in the legislative process. Their agendas or even topics of interest vary – the climate agenda and the telecommunications agenda, for example, operate in different ways due to distinct pressures and goals. Their resources also vary: groups with large numbers of employees and financial resources might act from multiple angles at once, for instance – and there are many other factors involved.

Some groups are so influential that their preferences are considered even before they lobby. For example, large companies responsible for a substantial number of jobs in the country, or even career NGOs, respected for their history of social struggles, have such weight. Other groups influence what topics will or won’t be debated by legislators – for instance, through the selection of which information will be presented to them, what information will be given to the public, journalists, which studies and analyses will receive funding and investment, and so on. Some exert influence during the implementation of legislation, helping to shape metrics to measure the success of implementation, influencing the practical approach taken by legislative guidelines, etc.

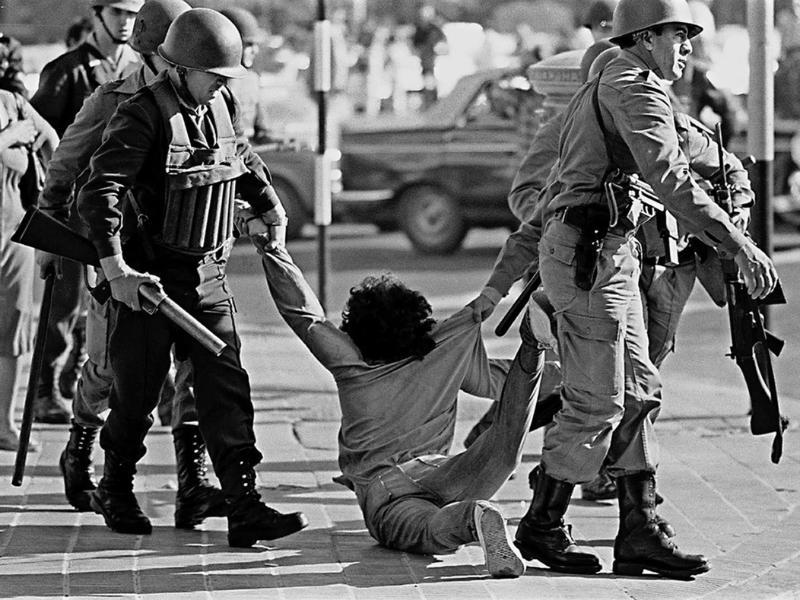

Interest groups do not only operate in democratic contexts but also in dictatorships – though in far fewer numbers and with limited capacities. They do not operate only in national contexts but also in subnational contexts – states, provinces, cities, municipalities, etc. They also operate in supranational contexts – here, the best example is the European Union.

The European Union is not a country but a set of institutions, international bodies, guidelines agreed upon by member-countries, and various agreements. For example, in the EU, some countries are part of the Eurozone, where the official currency is the Euro, while others are not – such as Sweden, Poland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary. Some are part of the Schengen Area, a space of free movement for goods, services, and people, while others are not – like Cyprus and Ireland. The economic bloc is thus a series of interconnections that apply fully or partially to its member-states, producing varying degrees of integration.

Lobbying in the EU offers unique opportunities, such as lobbying at multiple levels. The various redundancies in different agreements create opportunities to lobby the same issue in different instances – both in supranational spaces and in the national spaces where supranational decisions are discussed and implemented. Of course, strategies must be adapted. As Dür’s studies suggest, advocating in multiple instances can be counterproductive if the topic is not framed in such a way that its European character stands out, potentially harming interest groups’ pursuit of influence rather than helping them.

In such a prolific context for lobbying efforts, it is at least curious that in the last 20 years, two environmental regulations have been among the top 10 most targeted by lobbying. Politico, a newspaper focused on EU politics, reviewed over 5,000 pieces of legislation produced in the last 20 years and concluded that the due diligence regulation and the regulation on packaging and packaging waste were intensely targeted by lobbying efforts.

Due diligence is the legislation that requires companies to identify, prevent, and correct human rights violations and environmental damage throughout their supply chains, from raw materials to final products, including suppliers, transporters, and other partners. According to Politico, this legislation was the second most amended, with nearly 13,000 proposed amendments. And the efforts to weaken the regulation are quite creative. Some groups successfully advocated for delaying its implementation, while others were effective in excluding from deliberation, either partially or fully, groups directly affected. Obligations were reduced, the scope of affected companies was also narrowed, fiscalization mechanisms were weakened, and the legislation is now at its weakest moment due to the measures known as Omnibus Simplification.

The Omnibus Simplification is a sort of “mega package of deregulation,” promoted by some interest groups related to industrial sectors under the argument of reducing bureaucracy and improving European competitiveness, especially in a period of greater energy and geopolitical insecurity, like the current one. With apologies to the Latin – Omnibus means “for all” – it is difficult to conjure a more elitist action than justifying individual gains as an existential collective necessity.

As Martin Sandbu from the Financial Times argues, Trump and Vance’s efforts to convince the EU that its regulations were slowing development were almost in vain, given the substantial efforts of internal interest groups within the bloc to destroy environmental legislation. The curious thing is that the OECD itself describes European regulations as more streamlined than those in the U.S. – reiterating that having less regulation doesn’t mean having a more open market, vis a vis current U.S. protectionist measures.

Sandbu also questions the new “one in, two out” rule – where no new regulation should be introduced unless two old ones are scrapped at the same time – explaining that simply counting the number of regulations does not reflect whether they are beneficial or harmful. He explains that more EU-level regulations and fewer directives that need to be adapted separately by each member-state could help reduce the regulatory burden for businesses, giving them greater freedom in national contexts. Revoking already adopted rules – such as delaying the deadline for the end of gasoline-powered car sales – would give an unexpected advantage to companies that failed to adapt and harm the competitiveness of those that had already invested real resources to do so. Changing the rules in the middle of the game makes the market uncertain.

The other regulation, the one on packaging and packaging waste, was approved only at the end of last year – and already suffers from significant opposition. Aimed at reducing pollution caused by disposable packaging, the regulation sparked such intense disputes that the European Parliament had to launch an internal investigation to address accusations of abusive behavior and security breaches related to the discussion process.

Although these two pieces of legislation are among the 10 most targeted by lobbying, it is clear that they are not the only ones being targeted to be weakened. Another Politico article discusses the constant attacks on the ban on the sale of combustion vehicles by 2035, for example, showing just how willing the EU is to give in to attacks on the Green Deal. Essentially, the Green Deal is a set of policies from the European Commission aimed at making the EU carbon-neutral by 2050 – such as the two regulations discussed. In practice, the Green Deal revises every existing law based on climate criteria and introduces additional legislation related to circular economy, re- or deforestation, agriculture, green building renovation, biodiversity, and innovation.

When interest groups operate so intensely against a set of regulations, it is worth considering why. Who is interested in the deregulation of Europe? Who fears the Green Deal? And perhaps the most important question to ask: do you, yourself, fear the Green Deal?

References:

https://www.aclu.org/project-2025-explained?

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/17/trump-administration-project-2025?

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/psj.70010?af=R

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01402380802372662

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1070496514536396

https://www.ft.com/content/1d059c5a-56ab-4dc2-a022-03c63708322e