The Authoritarian League

It may be difficult to imagine now, but in the 1950s, the Republic of Venezuela had the fourth largest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the world—a way of measuring the quality of a country’s economy. Between the 1950s and 1980s, Caracas, its capital, was known as the Paris of the Americas. With such wealth, the country also held an enviable political position, as evidenced by joining the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in the 1960s. This is not to say the Republic was perfect. The wealth was substantial but poorly distributed. Those with money and connections rarely faced the law. The country struggled with systemic corruption, nepotism, and the traditional arrangements of a neopatrimonialist society—one that blurs the lines between public and private property and spheres. Still, in general, life was good.

In the 1990s, the price of oil dropped—non-OPEC countries began expanding their extraction and supply, the 1997 Asian financial crisis reduced demand, technological developments around the world increased extraction and processing capabilities in other regions, among other factors. The fall in oil prices was deeply felt in Venezuela, and a Lieutenant Colonel in the military knew how to exploit this sentiment and amplify it by also proposing a fight against corruption and social inequality. In 1998, Hugo Chávez, that Lieutenant Colonel, came to power, and with him, the Republic of Venezuela died, giving way to the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

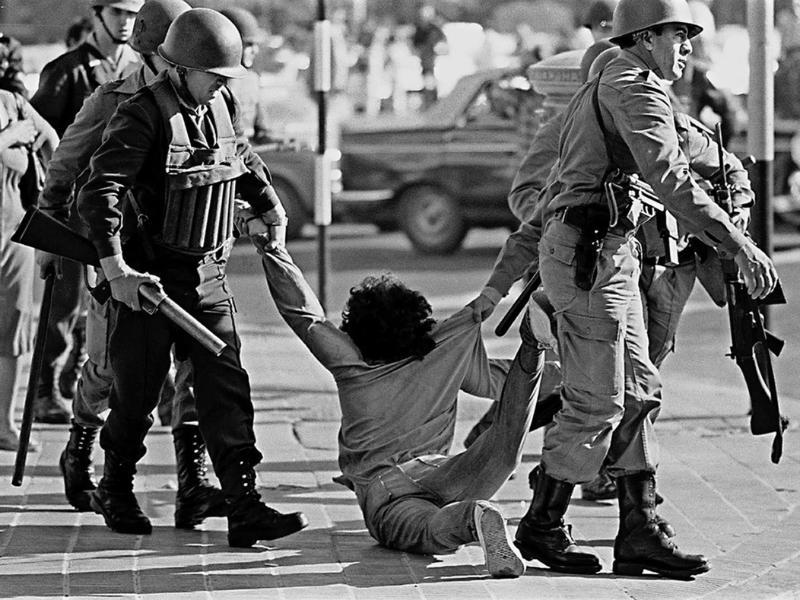

In the years that followed, Chávez worked relentlessly to suppress and eliminate all forms of accountability and transparency, dismantling the democratic institutions of his country until the Bolivarian State itself began to operate like a criminal organization. This was the era of the policy of omertà—say nothing about anything, silence being the least dangerous form of civil action. The years 2017 and 2021 saw corruption scandals amounting to billions of dollars. Manipulation of exchange rates created a parallel dollar market in the country, popularizing fraud and kleptocracy. The illegal dollars were used to buy real estate, but since the population could barely afford food, places like downtown Caracas came to resemble ghost towns. Hyperinflation followed the disappearance of the country’s foreign currency reserves, and Chávez’s supposed neo-Marxism was unmasked numerous times—such as in 2002, when 19,000 workers from the state oil company PDVSA were fired and replaced by loyal followers with no technical education. The country’s situation worsened even further when Chávez was succeeded by Nicolás Maduro, and massive protests erupted.

It seemed as though the Chavist regime would collapse on its own, but that did not happen. Rosneft, Gazprom, Lukoil, TNK-BP, and other Russian companies began investing heavily in the country. Russia’s sale of subsidized grain to Bolivarian Venezuela increased, replacing American and Canadian grain. Four billion dollars in Russian weaponry were sent to Caracas, joining the water cannons, gas, and other surveillance and protest suppression technologies sent by China. China also invested—and continues to invest—heavily in the country. When the United States imposed economic sanctions on the Bolivarian State, Turkey agreed to receive its gold exports, paying with food.

Cuban officials trained Venezuelan officers to use food rationing to their advantage—distributing food to the loyal and punishing dissidents with hunger. The Islamic Republic of Iran bought Venezuelan gold and paid with food and gasoline. Iranians allegedly also trained Venezuelans in repressive tactics and supposedly aided with training and technology in the construction of a drone factory—which failed. Iranians were sent to help repair oil refineries in Venezuela, and Venezuelans allegedly helped with money laundering and even falsified passports for Hezbollah members.

In the sphere of information, the media company Telesur, operating in Venezuela, is a Nicaraguan-Cuban enterprise, and its wave of pro-government information is amplified by Iran’s HispanTV, both using clips and footage mass-produced by RT (Russia Today)—a Russian outlet. Curiously, this network of autocratic narratives played a fundamental role in Mexico’s 2018 elections, spreading violent imagery of Mexico accompanied by messages calling not for better institutions or systematic poverty reduction, but for a populist-leaning autocrat. In the end, the network successfully promoted López Obrador.

Were it not for the help of this network of global autocracies, perhaps the Bolivarian State would have fallen. It certainly would not be as strong as it is today. Russian support might be explained by historical ties between the two countries. Chinese, Nicaraguan, and Cuban support might stem from ideological proximity. But what about Turkey? And Iran? Iran has no apparent historical ties with Venezuela. Ideologically, Bolivarian Venezuela is a left-wing internationalist state, while Iran is a conservative theocracy—almost antithetical to Bolivarianism. This autocratic mutual aid group includes anarchists, communists, theocrats, monarchists, and nationalists. It comprises distinct aesthetics, objectives, and values. It becomes clear that the arrangements among global autocracies have little to do with ideology, aesthetics, or history. If not explained by these elements, then what explains this strange union of autocrats?

At the end of World War II, the newly created United Nations, with the support of its members, proposed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—originally drafted by a Canadian scholar, a Chinese philosopher, a Lebanese theologian, and a French jurist. The Charter of the Organization of American States and the Helsinki Final Acts followed. The Geneva Conventions on the laws of war were later added. This group of treaties and the ideals that underpin them came to be known as the current global order. It is the fight against this order that unites autocrats so different from one another.

Make no mistake—the struggle is not ideological in nature, as once existed in the dichotomies of the Cold War. In the post-ideological era—a term used by Geddes, Wright, Kendall-Taylor, and Frantz, dictatorship specialists—conservatives, fascists, communists, and anarchists who once fought each other now unite against the current global order, seeking not a fairer or more equal system, but the survival of their regimes and political interests. An excellent example can be seen in a recent column by Vitória S. Fernandes for DPolitik, titled “The institutionalisation of anti-LGBT discrimination in Hungary: a global warning to democracy.”

Anne Applebaum, author of a seminal book on the topic, argues that the autocratic support network fosters the replacement of Human Rights with the Right to Development. Sovereignty instead of Political Rights, win-win cooperation and mutual respect instead of the Rule of Law and a democratic international system. The problem is that this harmless and generic language carries devastating potential.

The Right to Development is a domestic measure, making the international community unable to respond to abuses by any state against its citizens—unlike Human Rights. Sovereignty is a similar way of shielding governments from criticism over abuses. Win-win cooperation is the idea that the international system should be based on pragmatism and trade, not on values. Mutual respect is simply a softer version of Sovereignty.

The Russians, in particular, make use of the concept of multipolarity, which means a world that is not centered around the United States, but more equal and just, with greater distribution of power among countries. In recent years, this concept has gained a Neo-Marxist gloss, also meaning a kind of anti-colonial movement where the oppressed seize power from the oppressors. The obvious irony, as pointed out by Inna Bondarenko—a specialist educated at MGIMO, Russia’s elite diplomatic academy—is that Russia is not only a country with an imperial history—thus, one of the oppressors—but also one with current imperial attitudes. According to her, Russian diplomats are trained to view the world through the lens that might makes right, promoting territorial expansion and influence as a means of survival. Russia invaded a sovereign state—Ukraine. Its mercenary group—the Wagner Group—influences the politics of various African states directly, even through the use of force.

Of course, this does not mean that democratic states have not violated the very values they claim to uphold. On the contrary, examples could easily fill pages—a good one was given in a recent DPolitik column by Dimitri Cavalcanti, titled “The United States and the relativization of rights – The case of Mahmoud Khalil.” However, a system exists to judge them and seek reparations, and that system must be preserved. There is a difference between committing a crime and not being caught, and committing a crime and abolishing the legal system to commit others. It is therefore this system that autocrats are fighting against.

Interdependence and How It Fails in Its Promises

For a long time, it was theorized that trade would be the fundamental instrument for the democratization of authoritarian countries. Bill Clinton, former president of the United States, famously declared that increasing interdependence between the U.S. and China—where both economies are intertwined and depend on one another to survive—would be the driving force for China’s democratization, forcing a free market that would necessarily require a free flow of information to exist—elements of a democracy. Clinton, in a lecture at Harvard, stated: “Now there is no doubt that China has tried to repress the internet (laughter). Good luck! That is about like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall (laughter).” Some time earlier, his predecessor, Ronald Reagan—from a party and ideology quite distinct from Clinton’s—visited China and enthusiastically concluded upon return that “The first injection of free-market spirit has already invigorated the Chinese economy. I believe it has also contributed to human happiness in China and opened the path to a fairer society.” The American belief in interdependence was clear, regardless of party or ideology.

It goes without saying: China succeeded in nailing Jell-O to the wall. Interdependence driven by trade enabled China to compete with the U.S. for global hegemony and to put the entire current global order and its values at risk. The Chinese built a highly regulated and state-controlled internet, and instead of fostering a free flow of information, it operates as an amplifier of pro-government and pro-authoritarian narratives.Chinese development meant using interdependence to instrumentalize institutions such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—now with more members), transforming them into parallel forums that do not necessarily follow the rules of the global order. Not only that, but given its financial advantage, China turns these institutions into socialization structures—vehicles for spreading and internalizing authoritarian behaviors and ideologies. Not only did interdependence fail to produce democratization, but it actually produced the opposite effect.

The example of Venezuela, given at the beginning, illustrates a common outcome of interdependence—how autocracies use it to maintain authoritarian regimes that would otherwise not succeed or even remain in power. However, there is no more striking example than Russia itself in its war of aggression against Ukraine. The costs of the Western embargo are largely offset by the autocratic support network. Iran exports thousands of drones, North Korea sends munitions and missiles, Eritrea, Zimbabwe, Mali, and the Central African Republic offer support in United Nations votes, Belarus provides logistical support, Turkey, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan engage in triangular trade (allowing Russia to circumvent sanctions), India buys Russian oil, and China provides the main backing: security guarantees.

The Russian example is curious for revealing yet another effect of interdependence. During the Cold War, the West German Minister of Foreign Affairs—and later Chancellor—Willy Brandt proposed a doctrine known as Wandel durch Annäherung (“change through rapprochement”). Under this logic, West Germany would, through trade, change the USSR, making it more democratic and friendly toward Europe. In practical terms, the doctrine built pipelines connecting Bonn to Moscow not only for energy transfer, but also as physical symbols of the interconnectedness between the two nations. It is precisely these pipelines that are now used by Russia to apply pressure on governments, create energy insecurity within the European Union, and serve as instruments of autocratization through fear.

It is therefore clear that interdependence not only creates ideal conditions for strengthening existing autocracies but can also serve as a tool to autocratize democracies—or even as a weapon against them. Let us examine another example offered by Anne Applebaum. In her book, Applebaum recounts an explosion at a large factory in Warren, Ohio. Dozens of safety code violations were later found, and workers supporting their families were rushed to nearby hospitals. A detailed investigation revealed that the anonymous owner of the factory in the U.S. was a Ukrainian oligarch—who had made his fortune during the period when Ukraine was aligned with Russia—who was using the factory for money laundering. Ihor Kolomoisky and his factory in Ohio are just one of thousands of examples of how autocracies can use economic networks to operate within democracies.

Brandt’s confusion is the same one that affects the European Union when it recalls its own history of integration. Europeans tend to believe that interdependence among their economies is what created peace among them, when in fact interdependence was only possible because peace already existed—in the form of security guarantees provided by the Americans. In neither case—the pipelines nor the EU—did interdependence produce peace. At best, interdependence is a consequence of peace, not its cause.

Is This an Argument in Favor of Protectionism?

No. To critically reflect on the limitations and illusions of interdependence should not logically lead to protectionism, especially since protectionism carries other harms and limitations that fall outside the scope of this text. Instead, the logical response lies closer to critical regulation. In other words, the benefits of globalization should not be denied, but the free market must indeed be regulated in order to safeguard democracy.

Many of the challenges in today’s world are transnational by nature, and therefore require cooperation and collective action between countries and companies from various regions—for example, global warming, migration, terrorism, and so on. To advocate protectionism in this context would be to ignore the complex character of these challenges. Likewise, specialization is what elevated trade to its current level. Without a buying and selling network, specialization would mean a lack of essential goods in specialized societies, and an excess of their own products.

If today’s struggle has no direct historical parallel with the Cold War, then clearly there are no blocs to align with. The struggle is not necessarily against authoritarian countries, but against authoritarian actions—because these can emerge even within democratic states, given authoritarian influence, as has already been discussed. Furthermore, unthoughtful and unnecessary actions against these states in the name of fighting authoritarianism may have severe consequences. As argued by Brooks and Vagle in a recent article for Foreign Affairs, for example, separating the Chinese and American economies during peacetime could be disastrous.

According to them, such decoupling would affect China in the medium and long term by several orders of magnitude more than the United States, if carried out in partnership with its European allies—an interesting argument against the current American policy of stepping back from security guarantees in Europe. However, if this were to happen during peacetime, it is likely that allies would not have sufficient reason to go along—since their economies would also suffer considerably, unlike the American one. Not only that, but the United States would lose an excellent deterrent against a possible Chinese invasion of Taiwan (as the Chinese would likely not risk their economy that deeply).

It is therefore necessary, as Applebaum argues, to build and strengthen a network of lawyers, civil servants, and activists with practical experience dealing with autocrats. Military alliances and a shared intelligence network must be established to anticipate and halt violent state actions against civilians. Monitoring systems must ensure that sanctions against autocrats are effective, and a task force should be actively involved in combating fake news.

Economic transactions need to become more transparent—owners of financial enterprises and their stakeholders must be named in publicly accessible contracts. The transfer of dividends to tax havens could be banned, and practicing attorneys could be legally prohibited from working with such jurisdictions and governments. Finally, just as there exists an “authoritarian league,” a transnational anti-authoritarian effort is urgently needed.

Authoritarianism can be fought, stopped, and reversed—but action is necessary, while there is still time.

References

Applebaum, Anne. (2024). Autocracy, Inc.: The Dictators Who Want To Run The World. Random House: USA.

Bondarenko, I. (2025, April 14). I trained with Russian diplomats. I can tell you how they work. The Moscow Times.

Brooks, S. G., & Vagle, B. A. (2025, February 20). The Real China Trump Card: The Hawk’s Case Against Decoupling. Foreign Affairs.

Cavalcanti, D. (2025, April 2). The United States and the Relativization of Rights: The Case of Mahmoud Khalil. DPolitik.

Davies, M. (2017). Regional organisations and enduring defective democratic members. Review of International Studies, 43(2).

Fernandes, V. S. (2025, April 19). The Institutionalization of LGBTphobia in Hungary: A Global Warning for Democracy. DPolitik.

Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspectives on Politics, 12(2), 313–331.

Vox. (2025, April 4). How China is creating a new kind of internet [Video]. YouTube.