The escalation of tensions with the United States reignites the debate over Brazilian foreign policy and its actual autonomy in the face of pressure from a global power.

Brazil has, over the past few weeks, become a constant target of criticism from the United States, whose national policy is currently led by Republican Donald J. Trump. Recent events – such as the 50% tariff imposed on Brazilian exports to the U.S., along with biased criticism of PIX, the instant money transfer system developed by the Central Bank of Brazil – have placed Brazil–U.S. relations and the debate over Brazilian sovereignty in the spotlight of international politics. However, what can the history of diplomatic relations between the two countries teach us about the present situation?

The study of international relations is both multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary by nature, due to its broad scope. Within this field, diplomacy – the practice of interaction between states – is fundamental to understanding the course of international politics. Naturally, each country has its own history of relations, ranging across a broad spectrum that includes positions from neutrality (such as Switzerland) to more hostile or imperialist stances (such as Russia). Nevertheless, brief observations of Brazil’s diplomatic history with the U.S. are crucial to understanding what is currently happening between the two actors.

The classic literature on Brazilian Foreign Policy (PEB, in its Portuguese acronym), which includes major scholars such as Ricupero, Amado Cervo, Gerson Moura, and Mônica Hirst, among others, helps clarify the historical and structural nature of the relationship between the two countries. In discussing Brazil’s contemporary history, Gerson Moura analyzed the country’s foreign policy during President Dutra’s administration (1946–1951) in one of his key texts, where he coined an important term: “alignment without reward.” At that time, Dutra’s government inherited a Brazil positioned in the post–World War II context, marked by the geopolitics of the Cold War – an ideological dispute between the United States and the Soviet Union— and that was seeking a stronger presence in international affairs.

In this context, based on the bipolar logic of the period, Dutra’s foreign policy – which came to be understood as a tool for national development – aligned itself with the United States, becoming an important actor in disseminating northern values throughout South America.

The key point is that, based on the geopolitical alignment between Brazil and the U.S., there was an internal belief that Brazil would be granted certain advantages through a “special position” in its relationship with Washington. Following Brazil’s contribution in World War II as part of the Allied forces, it was interpreted domestically that the U.S. had acquired “moral obligations” toward Brazil.

However, reality turned out quite differently. Brazil, which had high expectations, did not achieve what it had hoped for. For instance, a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council – considered a strategic geopolitical goal for Brazil – did not come to be a reality.

Moreover, it was expected that Brazil would be recognized by its northern neighbor as a “special ally” and receive economic assistance, which also failed to happen. In short, Dutra’s foreign policy was characterized by ambitious expectations that never came to fruition, revealing the pragmatic nature of the United States – a country that will always prioritize its national interests, even if its allies do not benefit.

This behavior exemplifies realist theories in International Relations, as formulated by scholars such as E. H. Carr and Hans Morgenthau, which argue that states act to maximize their interests at the lowest possible cost. This logic is clearly echoed in a speech made by the current president of Brazil, Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, during his imprisonment in 2019:

“Americans think about Americans first, think about Americans second, think about Americans third, think about Americans fifth, and if there’s any time left, they still think about Americans. And yet, some Brazilian lackeys believe the Americans will do something for us. We are the ones who have to do something for ourselves. We must get rid of the inferiority complex, raise our heads. The solution to Brazil’s problems lies within Brazil.”

Indeed, the facts show that the Americans gave little thought to Brazilians and their political aspirations during what came to be known as the “alignment without reward” period.

However, it is still possible to reflect through a historical-analytical lens when examining periods of Brazilian foreign policy in which the country diverged from the position established during the Dutra administration. In other words, when Brazil began to act pragmatically and used foreign policy as a tool to achieve national development goals that could enhance its social and economic cohesion—such as the extensive and long-awaited process of industrialization. In this sense, what became known as the Independent Foreign Policy (PEI)—a paradigm explored in the work of Vizentini—can aid in understanding a more autonomous Brazil on the international stage. The author introduces the idea that PEI was a moment in which foreign policy (as understood during the governments of Jânio Quadros and João Goulart) was instrumentalized to achieve economic development objectives. Inspired by the national-developmentalist ideas of Getúlio Vargas—who sought to leverage opportunities within the international context to achieve industrialization—PEI developed around five fundamental principles: the expansion of external markets for Brazilian primary and manufactured products through tariff reduction within Latin America and the intensification of trade relations with all nations, including socialist ones; the autonomous formulation of economic development plans and the provision and acceptance of international aid within the framework of these plans; peaceful coexistence, maintenance of peace among states governed by antagonistic ideologies, and general and progressive disarmament; non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries, self-determination of peoples, and the primacy of international law; and the complete emancipation of non-autonomous territories.

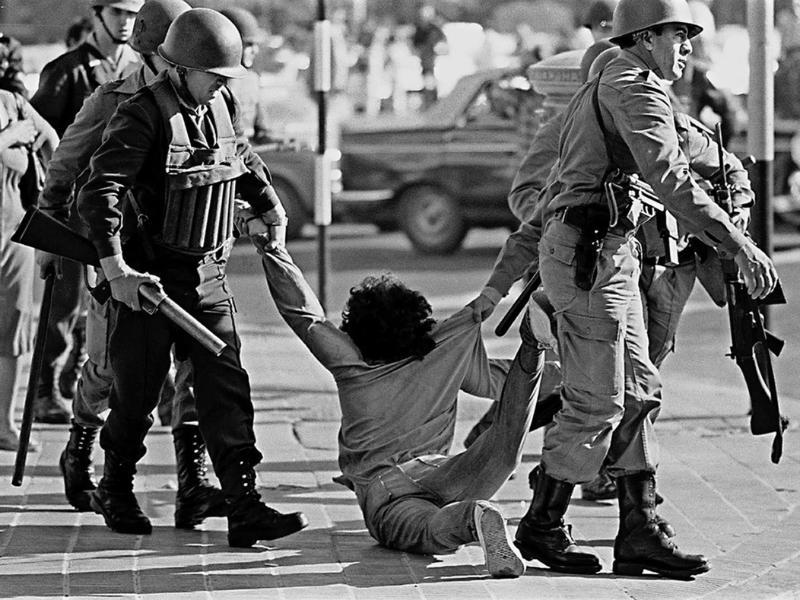

Nevertheless, it is evident that PEI proposed a set of principles affirming the sovereignty of Brazil and other territories—as highlighted in the fourth point—a topic that has dominated public and political discourse in recent weeks with the letter written by Trump to Brazil, announcing a 50% tariff on Brazilian exports. Furthermore, the first point reflects an attempt at international trade integration based on pragmatic and global guidelines. Indeed, the formation of the BRICS (a group of countries working toward political and diplomatic coordination in the Global South) undeniably echoes this PEI directive, as it promotes international cooperation that offers an alternative to the mainstream—that is, to international institutions of the Global North, such as the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. However, despite the existence of an autonomous development plan, the barriers imposed by reality prevented the continuation of the paradigm. Internal economic crises, increasing social contradictions, the advance of coup movements (1964), and, specifically regarding PEI, the lack of internal consensus were all factors that foreshadowed the end of an autonomy-centered foreign policy paradigm.

Nonetheless, with the military coup established, the paradigm guiding Brazilian foreign policy shifted once again, this time shaped by the bureaucratic apparatus of the authoritarian regime. Based on the contributions of Miyamoto and Gonçalves, it is possible to identify three different phases of Brazilian foreign policy with regard to the country’s international action guidelines. In the first phase, specifically during the government of Castello Branco, the literature recognizes the emergence of so-called “concentric circles,” characterized by alignment with the United States and the Western bloc (which interfered with pragmatic policy), as well as a geopolitical vision based on collective security and anti-communism. In this context, based on such characteristics, expectations were centered on economic cooperation, military security, and international prestige. However, the practical returns of this paradigm were limited and generated frustration among foreign policy formulators. The Alliance for Progress (a cooperation project between the U.S. and Latin American countries), for example, aimed to increase per capita income in Latin America, but failed to achieve even a 2.5% rise. Alienation within the defense system, furthermore, stemmed from Brazil’s distance from international decision-making centers, conditioned by the logic of collective security that subordinated the country to the U.S. nuclear umbrella. One can also observe the U.S. refusal of a Brazilian proposal to create a permanent multilateral force through the OAS, since the United States held unilateral power of intervention and preferred to retain it. It is worth noting that Brazilian foreign policy under Castello Branco acted similarly to earlier periods, such as the “alignment without reward,” as it sought benefits for the country through alignment with the United States.

In this context, the succeeding government, led by Costa e Silva, dealt with a growing frustration regarding foreign policy, giving rise to the so-called “diplomacy of prosperity.” Thus, a clear disillusionment with the United States and the outcomes of the Alliance for Progress became evident, leading to a shift in focus toward national economic development. Furthermore, an emphasis on sovereignty, the pursuit of technology, and South-South cooperation emerged. It is also important to highlight a contradiction within the U.S. political core: while, as a hegemonic power in the international system, it insisted that its allies remain aligned and refrain from establishing ties—whether economic or ideological—with the opposing bloc led by the USSR, the United States itself was simultaneously deepening its own dialogue and trade with its ideological adversaries.

In this way, the expansion of external markets, along with attracting capital and transferring technology, became priorities in overcoming the structural conditions that prevented Brazil from escaping underdevelopment. Development, therefore, became a prerequisite for national security, and critiques of the international order emerged, as the global system and its structures were perceived as obstacles to the progress of developing countries. Brazil began to question the concentration of power and technology in the hands of wealthy nations. Unsurprisingly, the ideas guiding this foreign policy paradigm created friction with the United States, which viewed Brazil’s diplomatic autonomy with suspicion. Consequently, the U.S. restricted economic and technological cooperation with Brazil, especially in the nuclear sector.

Finally, with the evolution of the international system, a weakening of the East-West conflict became apparent, accompanied by an intensification of the North-South narrative. In this context, the Médici administration abandoned integrative multilateralism and began to prioritize bilateral relations with states that served Brazil’s immediate national interests. This signaled a deepening of diplomatic autonomy, as the country became increasingly independent from ideological blocs, focusing solely on the defense of national development and sovereignty. Brazil also began to reject the principles of power balance and the maintenance of the international status quo. Projects such as the Itaipu Treaty (1973) further underscored the country’s ambition for regional hegemony, revealing expansionist tones in foreign policy that generated suspicion among other South American countries. In addition, Brazil sought new markets and allies beyond the U.S.–Europe axis, as illustrated by the opening of embassies in Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Libya.

In this sense, based on what has been presented regarding Brazilian foreign policy (PEB) during different periods of the country’s history, we observe attempts to gain advantages through alignment with the United States, as well as frustrations imposed by reality. For these reasons, Brazil sought its own paths to development, independent of the powerful neighbor to the north. Foreign policy, therefore, could be used as a tool to advance national interests, which can be seen in Brazil’s coordination with countries outside the North American axis. Based on this logic, the current Brazilian government’s engagement with BRICS countries (China, Russia, India, South Africa, etc.) is not surprising, considering that past moments of alignment with the U.S. brought frustrations and obstacles to development. The current Brazilian government thus sees multilateralism as a means to achieve national goals and is willing to align with Global South countries to pursue more favorable outcomes for Brazil.

In this broader context, the current president of the United States, Donald J. Trump, has adopted a series of measures that obstruct multilateralism and cause diplomatic rifts between countries. This reveals a protectionist and anti-globalist stance on the part of the Republican. One of the most recent examples was the withdrawal of the U.S. from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), a UN agency whose goal is to promote cooperation through education, science, and culture to foster peace on a global scale. The justification for this decision was ideological, as the American president claimed the agency was “ideological” and not aligned with the national interest, according to the U.S. State Department. Furthermore, the U.S. trade war against China—announced in the first half of this year—illustrates the previously mentioned point: Donald Trump uses his institutional powers to deepen a protectionist and anti-globalist agenda, causing disruption in the current international system.

The fact is that the actions of certain countries have effects that extend beyond their own borders—a phenomenon known in the international relations literature as the spillover effect, which refers to when decisions made by one actor produce unintended consequences for other actors in the system. A clear example of this is the issue of the trade war: in a globalized and interdependent world, tariff hikes cause economic damage that affects different local realities. Evidently, given the hostile stance of the U.S. toward countries that do not yield to its international interests—such as China and Brazil—these countries seek alternative paths for development through other platforms and with diverse partners. It is precisely in this context that the latest BRICS summit, held in Rio de Janeiro on July 6 and 7, 2025, gains relevance. The final declaration of the summit, specifically point 5, emphasized:

“[…] commitment to the reform and improvement of global governance, through the promotion of a fairer, more equitable, agile, effective, efficient, responsive, representative, legitimate, democratic, and accountable international and multilateral system, in the spirit of extensive consultation, joint contribution, and shared benefits.”

The values upheld by the current U.S. administration, therefore, run counter to the commitments of one of the world’s largest economic blocs. Moreover, with the absence of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping, social media users did not expect the event to have significant impact. However, the BRICS summit held in Rio de Janeiro proved otherwise. In addition, there is a clear connection between the speeches made by the Brazilian president at the event and the offensive measures adopted by the U.S. president in the days that followed. While delivering his speech, Lula spoke of the need for “a new financial system in the world,” according to a report by CNN Brasil. The president’s main argument was that international trade becomes less dynamic and more unequal as long as the U.S. dollar maintains its “sovereignty.” In fact, the international financial system is based on the structures of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank—institutions that use the dollar as their primary currency. Beyond that, according to the same CNN Brasil report, Lula argued that the current financial system does not adapt to the realities of emerging economies and poorer countries.

Historically, it is worth noting that core institutions of contemporary capitalism have been used to impose agendas aligned with the interests of wealthy nations on developing countries. A stark example of this is the adoption of the Washington Consensus (1989) by peripheral countries. The policy, developed in the U.S., aimed to regulate international trade by promoting the liberalization of peripheral economies seeking development through industrialization. In this sense, the path to development would be financed by institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, on the condition that countries open their markets—which significantly reduces the competitiveness of domestic producers—and implement other neoliberal measures, such as the privatization of state-owned companies. The experience of countries, including Brazil, with the Washington Consensus translated into increased external vulnerability, as their development became dependent on investments from those institutions. Furthermore, there was an increase in economic deficits during the 1980s, caused by various factors, including external debt, which resulted from liberal macroeconomic policies.

Consequently, it is no coincidence that President Lula delivered a speech with critical undertones regarding the hegemony of the dollar in the international system. Nor is it a coincidence that the Republican president responded by retaliating against Brazil. By criticizing democratic institutions, the U.S. president crafted a narrative suggesting that Brazil is a dictatorship. Trump used the term “witch hunt” to describe the legal proceedings involving former president Jair Bolsonaro, who is under investigation for conspiring against democracy, attempting a coup d’état, among other crimes. Based on this, the U.S. imposed a 50% tariff on Brazilian exports. This constitutes both a threat and an attack on our country’s sovereignty, carried out with the intention of undermining Brazilian foreign policy, which dares to stand up to Washington. In truth, Brazil is showing that northern winds do not turn its mills—and it resists, which is essential to preserve a margin of independence in the face of the uncertain paths unfolding today.

References:

BRASIL. Ministério das Relações Exteriores. Declaração de Líderes do BRICS — Rio de Janeiro, 06 de julho de 2025. Nota à imprensa n.º 298. Brasília: MRE, jul. 2025. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/canais_atendimento/imprensa/notas-a-imprensa/declaracao-de-lideres-do-brics-2014-rio-de-janeiro-06-de-julho-de-2025. Acesso em: 31 jul. 2025.

GONÇALVES, Williams; MIYAMOTO, Shiguenoli. Os militares na política externa brasileira: 1964-1984. Estudos Históricos (Rio de Janeiro), v. 6, p. 211–246, 1993.

MOURA, Gerson. O alinhamento sem recompensa: a política externa do governo Dutra. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil, 1990.

NAKAMURA, João. “Queremos novo sistema financeiro no mundo”, diz Lula na Cúpula do BRICS. CNN Brasil, São Paulo, 7 jul. 2025. Disponível em: https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/economia/macroeconomia/queremos-novo-sistema-financeiro-no-mundo-diz-lula-na-cupula-do-brics/. Acesso em: 31 jul. 2025.

SOSA, Ana. Lula sobre EUA: ‘americano pensa em americano em 1º, 2º e 3º lugar’. Roma News, 22 jan. 2025. Disponível em: https://www.romanews.com.br/brasil/lula-sobre-eua-americano-pensa-em-americano-em-1-2-e-3-lugar-0125. Acesso em: 31 jul. 2025.

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE. The United States Withdraws from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Press release, 22 jul. 2025. Disponível em: https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/07/the-united-states-withdraws-from-the-united-nations-educational-scientific-and-cultural-organization-unesco. Acesso em: 31 jul. 2025.

VIZENTINI, Paulo Fagundes. O nacionalismo desenvolvimentista e a política externa independente (1951-1964). Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, Brasília: IBRI, v. 37, n. 1, 1995.