The Dependency Theory emerged in an attempt to analyse Latin American economies and their relations with the rest of the world. It analyses the process of integration of peripheral countries into international capitalism, emphasising the problems that this process brings to development.

Dependency Theory has been considered ‘Latin America’s greatest contribution to the social sciences’1, since a Latin American perspective was used to understand the issue of Latin American development. Thus, it is important to understand this theoretical school due to its profound impacts on the history of social thought and international development in Latin America.

This text aimed to discuss Dependency Theory and its impacts on Latin America, arguing that this school was of fundamental importance to Latin American economic thought, but is not exempt from criticism. After the introduction, the emergence of Dependency Theory was discussed, analysing its foundations, its main authors and aspects. The author then identified the impacts of this theory on international development — theories and policies — in Latin America, using the case of the Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC) government to understand how one of the main thinkers of this theory used his power to put his ideas into practice. After the case study, some criticisms and debates related to Dependency Theory were raised for a deeper understanding of the theory. Finally, the author presented her final reflections, concluding that Dependency Theory had a profound impact on Latin American history, but that the criticisms it received led to its downfall.

The emergence of the theory

Dependency Theory emerged in Latin America between the 1950s and 1960s, representing a critical effort to understand the new aspects and limits of economic development in the region. This was because, after the economic crisis of 1929, Latin American countries began to orient their economies towards industrialisation, seeking to replace imports of products from central countries. Brazilian economist Theotônio dos Santos, one of the leading figures in Dependency Theory, points out in his book, ‘Dependency Theory: Balances and Perspectives’ (2002), that the development that began in the period mentioned above was part of a global economic hegemony led by imperialist forces that, even in crisis, still wielded considerable power in the world. Thus, Dependency Theory argues that the global political-economic system is essential to understanding national and regional units, with the economies of peripheral countries conditioned by the development of central countries.2

In addition to the 1929 crisis, other antecedents are also important for understanding the emergence of the theory. Blomström and Hettne (1984) argue that the nationalist critique of Eurocentric imperialism and neoclassical economics, led mainly by Raul Prebisch and the UN Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC), influenced the emergence of the theory. ECLAC was founded in 1948 with the aim of reflecting on the socioeconomic reality of Latin America and defending the national development project through industrialisation with the support of the bourgeoisie. Industrialisation was understood as a ‘binding and articulating element of development, progress, modernity, civilisation, and democracy.’3 ECLAC scholars, called structuralists, argued that Latin America’s underdevelopment was directly related to the interests of the ‘imperial centre,’ which sought a source of agricultural products and raw materials in the region, thus discouraging industrialisation.4 However, after the various civil-military coups that took place in Latin America in the 1960s, the structuralist perspective began to receive criticism from different segments, including left-wing researchers. It was from this context that the creation of Dependency Theory began.

Blomström and Hettne (1984) summarise the central ideas of the Dependency school in their work. It is important to note that these ideas are not accepted by all aspects of the school, as the movement was not homogeneous, but this was an attempt by the authors to facilitate understanding of the central elements of the theory. They are:

- Underdevelopment and the expansion of industrialised countries are directly and closely related.

- Development and underdevelopment are distinct characteristics of the same economic process.

- Underdevelopment should not be considered a first step in the process of economic development.

- Dependency is not only an external phenomenon; it is also present in the internal structures — social, ideological, and political — of peripheral countries.

Considering the above ideas, it is important to understand the concept of underdevelopment from the perspective of dependentistas in order to gain a deeper understanding of the theory. The perspective of Celso Furtado, one of the great theorists of this school, is used here. In his book ‘The Myth of Economic Development’ (1974), Furtado explains that underdevelopment is the result of the global industrialisation process that began with the Industrial Revolution. The former stems from the increase in labour productivity generated by the reallocation of resources to obtain comparative advantages in international trade. The decisive factor for income distribution in underdeveloped economies is the pressure created by the modernisation process. This attempt to reproduce the consumption patterns of central countries reflects a process of cultural domination of developed countries over peripheral countries. The decisive factor for the dependence of the periphery on the centre is, therefore, the fact that underdeveloped countries remain cultural satellites of developed countries and have a much lower process of capital accumulation than the latter. The phenomenon of dependence thus begins with the external imposition of consumption patterns that can only be sustained through the generation of surpluses in foreign trade.

Three main strands of Dependency Theory can be distinguished5:

- Structuralist critique: theorists linked to ECLAC have made critical analyses of conventional explanations of development. Notable authors in this group include Oswaldo Sunkel, Celso Furtado and Raul Prebisch.

- Neo-Marxist current: emerged in the mid-1960s, using Marx’s historical-dialectical materialism to criticise traditional perspectives on development, as well as the analyses of the previous current. This current is based mainly on the works of Theotônio dos Santos, Vânia Bambirra, and Rui Mauro Marini, and other researchers from the Centre for Socioeconomic Studies at the University of Chile. André Günter Frank, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and Enzo Faletto can also be considered part of this current, although there are differences between their perspectives. For example, Cardoso and Faletto fit into ‘a more orthodox Marxist current due to their acceptance of the positive role of capitalist development and the impossibility or lack of need for socialism to achieve development.’6

- Consumption: this is the phase of discovery of this theory in the central countries. The authors of this current also differ in their perspectives, some using only the concept of dependence, others considering dependence only as an external factor.7 Authors such as Guy F. Erb, Robert Pacckenham, David Ray, Samir Amin, Walter Rodney, Arghiri Emmanuel and Keith Griffin can be cited.

The impacts in Latin America

Given the expansion of Dependency Theory and the various debates surrounding it, it is pertinent to understand its influence on international development policies and theories in Latin America.

Dependency Theory was the first contribution by peripheral countries to the study of development and provided important conceptual tools for understanding the Latin American case. In addition, it was the first theory in the region to overcome geographical barriers and influence the academic environment of developed countries.8 Dependency Theory provoked a reordering of social science issues in Latin America, bringing new social concerns to socioeconomic analysis and new methodological options inspired by the theoretical foundations of researchers from this school.9

The accumulation of new methodological proposals in Latin America…

‘reflected the growing density of its social thought, which went beyond the simple application of reflections, methodologies or scientific proposals imported from central countries to open up its own theoretical field, with its own methodology, its identity theme and its path to a more realistic praxis’ (dos Santos, 2002, p. 24).

An example of this influence was the creation of the World System Theory, which Theotônio dos Santos (2002) and several other authors consider an evolution of the Dependency school.

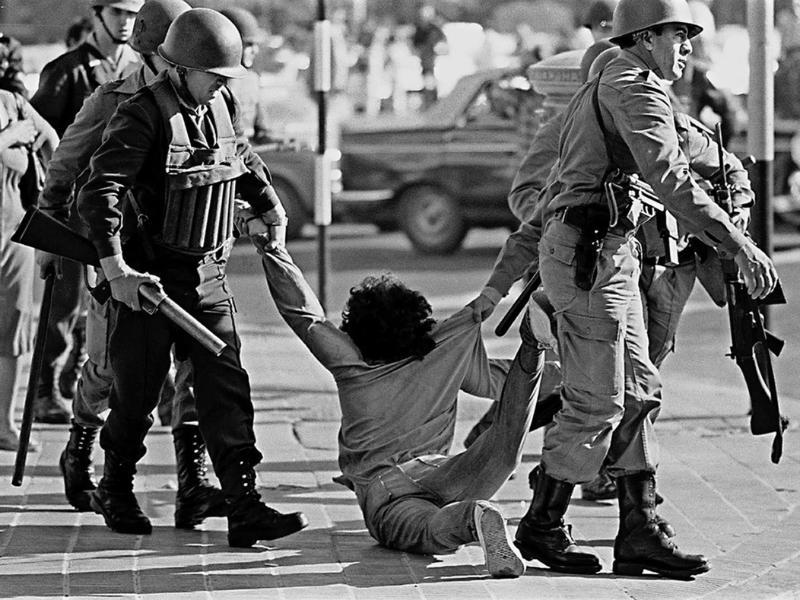

However, it was not only in the academic field that Dependency Theory had an impact on Latin America. From its inception, the theory was influenced by the political landscape of the region, as the 1960s represented a time when left-wing revolutionary movements had suffered a temporary defeat and were converging mainly in Chile to gather strength for a new offensive.10 In 1964, the military coup in Brazil established a violent dictatorship, in which several left-wing thinkers were exiled, such as Theotônio dos Santos, Enzo Faletto, and Fernando Henrique Cardoso. They ended up meeting in Chile, and the country became one of the most important centres of Latin American resistance against dictatorships.11 It was in this context of revolution that Dependency Theory was created.

In this sense, the theory significantly influenced the design of Chile’s Popular Unity (UP) programme, the party coalition that governed Chile between 1970 and 1973 under the leadership of President Salvador Allende. UP sought to break the basic axis of oligarchic-imperialist domination and advance towards socialism through agrarian reform and the nationalisation of large monopolistic companies in industry, mining, etc.

In this way, UP attempted to put into practice the concept that had been demonstrated by the Cuban revolution and confirmed by theoretical and empirical research on dependent capitalism: that imperialism was an internal constituent element of the system of domination and that, in order to carry out a consistent policy of national and social liberation, it was necessary to go beyond it, advancing towards socialism.12

The UP managed to nationalise mining, but suffered a military coup in 1973 before it was able to fully implement its project on the path to socialism.

In addition to Chile, Dependency Theory influenced several revolutionary programmes throughout Latin America, such as Liberation Theology in Peru. However, here we will focus on the impacts of this theory on the government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC) in Brazil (1995-2002).

The FHC Government and Dependency Theory

According to Sanchez (2003), the publication of Cardoso and Faletto’s work, ‘Dependency and Development in Latin America,’ laid the foundations for the historical-structural aspect of the Dependency school. “Cardoso led a new wave of dependentistas who believed that dependency relations could very well lead to development – what they called “associated dependent development”. (Sanchez, 2003, p. 38).

FHC distanced himself from the revolutionary ideas of the neo-Marxists, who believed that development and underdevelopment are part of the same historical process of capitalist accumulation. Cardoso, however, believed that development and underdevelopment were realities, albeit linked by the same capitalist structure, distinct and opposite. For Cardoso, capitalism had no borders, and each country should play a specific role. From this perspective, he disagreed with the postulate that dependence only brings harm to peripheral countries. FHC considered it impossible for a country to develop autonomously.13

“[…] FHC attributed responsibility for Latin American underdevelopment more to local elites than to the ability of central countries to create obstacles to the development of the capitalist periphery.” (Ferreira, 2016, p. 477).

To achieve development, then, peripheral countries should deepen their relations with the external market, giving decision-making power to the centres of international capitalism and private corporations, and creating policies to encourage the establishment of multinational companies.14

Cardoso also had a critical attitude towards the figure of the protectionist and regulatory state, which made him one of the most influential people in the country in both the academic and political spheres15. Thus, FHC held various positions in Brazilian politics and became President of the Republic in 1995, a position he held until 2002.

In line with his ideas, which he had been promoting since 1960, when he took office, FHC introduced some changes in the Brazilian economy to create better conditions for the entry of international capital, and even adopted some neoliberal measures that he considered necessary to modernise the state and promote dependent development. These included measures such as currency stabilisation, privatisation, reduction of fiscal barriers to imports, deregulation of labour relations, economic liberalisation, and reduction of the state’s regulatory role in the economy.16

Even though he remained faithful to his dependentist project, FHC was unable to achieve the economic development he had hoped for from the implementation of his theory. This is because, by subordinating the country to the global economy, Cardoso reinforced the speculative tendency of capital operating in Brazil and also increased income concentration, the public deficit and ‘a prolonged financial crisis/instability resulting from the aggressive interests of parasitic speculative capital’ (Ferreira, 2016, p. 486).

Many criticised Cardoso’s attempt to implement Dependency Theory in his government, as it had already lost its credibility in the academic world, and the mistakes of the FHC government only worsened the school’s image.

The criticism

Criticism of Dependency Theory gained momentum in the mid-1970s, even from Latin American authors. In 1975, Enrique Semo presented in ‘La Crisis Actual del Capitalismo’ a critique based on the concept of interdependence as a trend in the international economy. Another criticism was that of including the concept of economic autonomy in the definition of development. Sanchez (2003, p. 35) argues that if an underdeveloped country is structurally dependent and what would characterise a developed country would necessarily be economic autonomy, then ‘economic prosperity is unattainable by definition’. In addition, the author states that dependency theorists do not offer proposals for economic challenges such as improving productivity and economic growth, combating inequalities, and diversifying exports.

The Dependency school received these and several other criticisms. Thus, some authors mobilised to develop counterarguments. In 1978, Vania Bambirra wrote the book ‘Teoría de la Dependencia: una anticrítica’ to respond to the main criticisms levelled at the school. Bambirra shows that several of these criticisms were based on misinterpretations and superficial analyses and were attributed to dependency positions that were never defended by them. In 1975, Semo stated that many third-world countries were developing along capitalist lines and increasing their international influence, using OPEC countries as an example. In her analysis, Bambirra agrees with Semo regarding the manoeuvring capacity that these oil-producing countries gained in the face of imperialism, but she states that Semo does not provide answers as to who would control investments in these countries.

According to Bambirra, most of the new investments in the oil industry in OPEC countries were directly controlled by large multinational corporations, which would perpetuate the models of dependent capitalism. ‘Therefore, it seems absolutely utopian to think of a substantial change in dependency relations and their replacement by interdependence relations.’ (Bambirra, 1978, p. 97).

However, despite attempts by dependentistas to refute the criticisms, the theory continued to decline, especially after the fall of the socialist regimes. At that time, Marxism was invalidated as a theoretical paradigm because it was the ideological-intellectual foundation of these regimes, which led to the delegitimisation of Dependency Theory:

“because the experience with “real socialism” proved to be an absolute failure, its Marxist intellectual foundations were also widely considered fundamentally flawed. Dependency, in its status as an allied theory, suffered the same fate.” (Sanchez, 2003, p. 40)

An example of this is that in ‘The End of History’, Fukuyama devotes a chapter to Dependency Theory, calling it an enemy that must be destroyed in order for capitalism and liberalism to achieve their final victory in the world.17

This column sought to understand the origins of Dependency Theory, its foundations, main aspects, and influences on international development. As seen throughout the text, the theory has development as its object and critically analyses the relations between peripheral and central countries. However, this school is not homogeneous; it has produced different theoretical currents and has been the target of various criticisms and debates.

The case study of the FHC government in Brazil was chosen to understand how one of the leading figures of Dependency Theory used his influence as president to put his ideas into practice, since by the time FHC became president, Dependency Theory had already been subject to considerable criticism. When analysing his government, it can be concluded that, contrary to what many believe, Cardoso did not break with his ideas from Dependency Theory to promote neoliberal policies. He defended a project of associated dependent development and remained faithful to his theory, implementing policies to attract international investment to Brazil. However, even in Cardoso’s attempt to put the theory into practice, it was discovered that his administration had several flaws that contributed to the criticism of the Dependency school.

Despite the various controversies surrounding the theory, however, its influence in Latin America cannot be denied. It influenced both the academic and political spheres and is considered one of the most important theories in Latin America.

Sources

Bambirra, V., 1978. Dependency Theory: An Anti-Critique. Psychology. Mexico: Era Ediciones. Available at: https://sociologiadeldesarrolloi.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/104250818-teoria-de-la-dependencia-una-anticritica-vania-bambirra.pdf [Accessed on: 5 January 2023].

Blomström, M. and Hettne, B., 1984. Theory of Development in Transition: The Debate on Dependency and Beyond: Responses from the Third World. Zed Books.

Cardoso, F.H. and Faletto, E., 1970. Dependency and Development in Latin America. Social Sciences Library. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

Dos Santos, T., 2002. Dependency theory: Assessment and perspectives. Psychology. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. Available at: https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/5499595/mod_resource/content/ 1/Theot%C3%B4nio%20dos%20Santos%20-%20The%20theory%20of%20dependence%20-%20Assessment%20and%20perspectives.pdf [Accessed on 12 December 2022].

Ferreira, R.L., 2016. Don’t forget what he wrote: sociologist Fernando Henrique Cardoso and the (practice of) Dependency Theory. Temporalities [Online], 8(1), pp.469–486. Available at: https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/temporalidades/article/view/5693 [Accessed on 2 January 2023].

Furtado, C., 1974. The Myth of Economic Development. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

Gonçalves, R.S., 2018. Theory and practice in Fernando Henrique Cardoso: from the nationalisation of Marxism to political pragmatism (1958-1994). São Paulo: University of São Paulo. Available at: https://doi.org/10.11606/T.8.2018.tde-29102018-161356 [Accessed on 10 December 2022].

Sanchez, O., 2003. The rise and fall of the dependency movement: does it inform underdevelopment today? psicol. Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe, 14(2). Available at: https://eial.tau.ac.il/index.php/eial/article/view/893 [Accessed on: 29 December 2022].

Semo, E., 1975. The current crisis of capitalism [Online]. 1st ed. Economy. Mexico: Ediciones de Cultura Popular. Available at: https://catalogtest.lib.uchicago.edu/vufind/Record/91922 [Accessed on 7 January 2023].

Silva, G.J.C., 2008. The theory of dependency: reflections on a Latin American theory. Hegemony: Journal of Social Sciences [Online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.47695/hegemonia.vi3.33 [Accessed on 20 December 2022].

Endnotes

- (Sanchez, 2003, p. 31) ↩︎

- (Silva, 2008). ↩︎

- (Ferreira, 2016, p. 472). ↩︎

- (Ferreira, 2016) ↩︎

- (Silva, 2008) ↩︎

- (Dos Santos, 2002, p. 19) ↩︎

- (Dos Santos, 2002, p. 19) ↩︎

- (Silva, 2008) ↩︎

- (Dos Santos, 2002) ↩︎

- (Bambirra, 1978) ↩︎

- (Bambirra, 1978) ↩︎

- (Bambirra, 1978, p. 24). ↩︎

- (Cardoso; Faletto, 1970) ↩︎

- (Ferreira, 2016) ↩︎

- (Ferreira, 2016) ↩︎

- (Ferreira, 2016) ↩︎

- (Dos Santos, 2002) ↩︎