By Nicolas Zupardo Dutra* and Cinthya Araújo

In December 2024, we published a column discussing the Syrian rebel offensive and its implications for the country’s future. This article can be understood as a continuation of the original column, essentially revisiting Syria and seeking to understand what has happened over the past nine months. In order to make the understanding from the most effective perspective, this is the first part of the analysis, focused on understanding the external aspects of the current government. Therefore, this column will address how the vast array of foreign actors, some with a military presence within the country, including Israel, Russia, Turkey, the United States, and others, operate within the country.

Contextualization

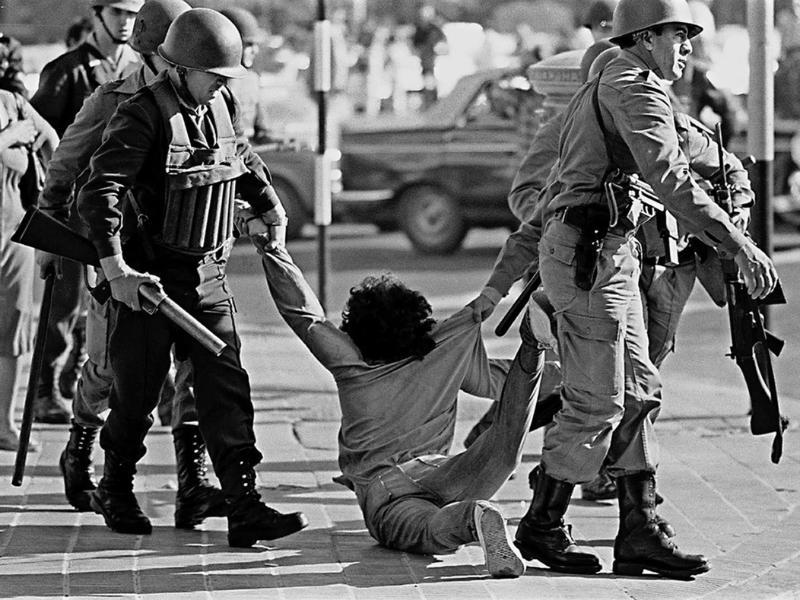

The Syrian Civil War had a dramatic turn around when at the end of 2024, rebel groups launched an offensive, taking the capital, Damascus, in less than 2 weeks, and ending the Assad family’s more than 50-year rule.In short, the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s government can be understood through a continuous deterioration of his power base, due to worsening living conditions, the lack of basic services, and dissatisfaction even in traditional areas loyal to the regime. Parallel to this process, rebel groups, especially the jihadist group led by Ahmed Al-Sharaa, Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), maintained active pockets of resistance and developed their military capabilities against the Assad regime through a process of institutionalization of the HTS. In this sense, the regime’s economic disarticulation, coupled with the gradual withdrawal of partners such as Russia and Iran, given other strategic priorities, resulted in December 2024 providing an ideal paradigm for a rebel offensive. Thus, although Bashar al-Assad’s fall was abrupt, it was due to a continuous deterioration of his power base, marked by the erosion of central authority and territorial fragmentation. It is within this context that the current Syrian Transitional Government, headed by Ahmed Al-Sharaa, emerged. Although its inauguration effectively ended a cycle of the Syrian conflict, the new government ushered in a phase of uncertainty regarding the new Syrian state.due to the wide range of challenges present within Syria, including an economic crisis aggravated by international sanctions, the erosion of central authority and the initial difficulty in recognizing the Syrian Transitional Government, due to its connections with former jihadist organizations.

The Syrian diplomatic offensive

Within this context, Syrian foreign policy has been divided into two main axes over the past nine months: first, the recognition of the new Syrian Transitional Government as an internationally legitimate actor, and second, the reconstruction and stabilization of the country, both from an economic and security perspective, with this process essentially led by Ahmed Al-Sharaa. The first axis to be addressed will be the recognition of the current Syrian government as a legitimate actor, something made difficult by what can be perceived as international concern surrounding the post-Assad Syrian government, as the group Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) was initially established as an explicitly jihadist group with a history of human rights violations. The group has indeed been designated a terrorist organization by a number of countries, including the United States, Russia, Turkey, and the European Union, and Al-Sharaa himself has been designated as an individual supporting terrorism.

This paradigm implied a certain recklessness on the part of other actors in the International System to engage effectively with the current Syrian leadership, something exemplified by the debates between policy makers of the United States, with the same debate taking place within the European Union, has focused on expanding diplomatic relations with Syria, given the government’s history with jihadist groups. In this regard, the Syrian leadership has engaged in a veritable diplomatic offensive around the world, attempting to present the current government as composed of actors capable of exercising local governance, providing security, and engaging pragmatically with surrounding countries, far removed from their jihadist past. Soon, the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates, under the command of Assad Al-Shaibani, engaged in a massive effort, carrying out 1,500 diplomatic engagements in approximately nine months with approximately 87 countries around the world, as well as international institutions such as the International Criminal Court and a number of United Nations bodies. This effort, centered on recognizing the Syrian Transitional Government as the legitimate authority over Syrian territory, collected significant results. Supported by the intercession of actors such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia, both eager to see a government in Damascus aligned with their interests and far from Iranian influence, the new Syrian government secured significant relief from the main sanctions imposed on Syria during Assad’s rule and recognition of its authority over Syria by a number of states, ranging from China and Russia to the European Union and the United States.

In this sense, it is worth briefly highlighting the relationship between Syria and its two main international partners: Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Both states play a key role in the normalization of the new Syrian government and, in line with the second axis mentioned above, the country’s reconstruction. As discussed previously, Saudi Arabia plays a critical role in Syria’s reintegration into the international system, as demonstrated by Saudi intercession with the United States, contributing to the meeting between Al-Sharaa and Donald Trump in May of this year, normalizing relations between the two states. Furthermore, the Saudis are one of the main sources of funding for Syria’s reconstruction, as demonstrated, for example, by billion-dollar investment proposals aimed at recapitalizing Syrian infrastructure. Turkey, in addition to its diplomatic and financial role, has a relationship that focuses more on security issues. The Syrian Transitional Government maintains a significant military partnership with the Turkish government, including intelligence sharing, military exchanges, and, recently, transfers of Turkish military equipment to Syrian forces. Simply put, both states are a key component of Syrian foreign policy, accounting for nearly a third of Syrian diplomatic engagements last year.

Within this paradigm, it is worth highlighting the role of other actors within Syria. In a brief analysis of the main actors, two immediately stand out: Russia and the United States. Both still maintain a significant military presence inside Syria, in the Russian case mostly contained within the Tartus naval base and the Hmeimim air base, while US forces maintain a constellation of bases throughout northeastern Syria, in partnership with Kurdish militias. Currently, the Russian military presence in Syria is a remnant of the military support the Russians provided to Assad, in exchange for which the Russians had the right to use strategic points in Syria to enable their strategic projection in the Middle East and Africa as a whole. This same presence finds itself in a delicate position due to the Russian government’s current sheltering of the Assad family and Western pressure to close these bases. However, the Syrian government has currently adopted a pragmatic stance, recognizing the Russian military presence in the country but seeking to extract diplomatic concessions from the Russian state. The dynamics surrounding the US military presence in the country revolve primarily around two issues: tensions surrounding the Kurdish minority and the preservation of its autonomy, which will be addressed in more detail in the second part of this column, and the US interest in preventing the resurgence of the Islamic State (IS) in the region. In this sense, the US presence is also a remnant, but from the intervention against IS throughout the Syrian civil war. Despite discussions regarding the de facto withdrawal of all US troops from the region, this presence remains due to operations carried out against IS, which are a point of cooperation between the Syrian Transitional Government and the United States, given the threat posed by IS cells to Syria’s long-term stability. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that this cooperation already originated from the cooperation between HTS and the US government in eliminating IS cells. Al-Qaeda inside Syria.

The external challenges of Syrian security and reconstruction: the israeli role

It is clear, then, that despite the Syrian government’s success in achieving international recognition and taking significant steps toward economic reconstruction, security challenges remain for Syria’s overall reconstruction, with two notable cases emerging in Lebanon and Israel. First, Lebanon, which was marked by clashes between Syrian military forces and local tribes associated with the Lebanese group Hezbollah, on the border of the two countries throughout March 2025. Despite initial tensions, in which Syria accused the Hezbollah executing three of its soldiers and Syrian forces having responded by bombing Lebanese positions, both governments, after the outbreak of this crisis, reached an agreement in search of diplomatic means to resolve this problem, emphasizing the importance of collaboration and bilateral coordination.There was, however, no direct dialogue with the Hezbollah or affiliated groups, only the initiative to delimit their borders based on cooperation with theLebanon.This initiative is important due to the range of irregular actors that permeate the border of both States and their role in activities such as arms and drug trafficking.

The Israeli case, in turn, presents significant complexity, given that two days after the fall of the Al-Assad government, Israel sought to weaken Syria’s military power, seeking, according to Israeli sources, to prevent it from being recklessly used by the Syrian Transitional Government. Using the justification of the latter’s jihadist affiliations, it launched around 500 airstrikes, destroying much of Syria’s weapons and military stockpiles, including, reportedly, chemical weapons. Al-Sharaa’s response to the situation was not a counterattack; it declared, privately and publicly, that Syria, under its rule, would not be a launching pad for attacks on any neighboring state, including Israel. Ahmed Al-Sharaa declared that he would continue to abide by the 1974 ceasefire agreement and asked foreign powers for ways to pressure Israel to continue adhering to the agreement. Despite this, Israeli military forces continue their operations inside Syria with some frequency, and negotiations by the Transitional Government have yielded few results, which presents a problem due to Israel’s clear military superiority and its ability to exert pressure on theSyrian State. Currently, Israeli military personnel occupy a swath of Syrian territory, and Israeli airstrikes on Syrian military infrastructure are common, totaling about 90 so far this year. During the writing of this text, the Israeli Air Force conducted strikes against Syrian military depots in Homs and Latakia.

Furthermore, another aspect worth highlighting is Israeli interference in the new phase of the internal Syrian conflict, especially in matters related to the Druze ethno-religious minority. Although this conflict itself will be addressed in more detail in the second part of this analysis, current Israeli interference can be understood through their interest in an autonomous Druze region in southern Syria as part of a broader buffer zone in the region. This project was already coveted by Israeli politicians before the fall of Al-Assad due to the presence of Iranian militias in the region at the time, and the fall of the Assad government provided the necessary opportunity for its consolidation.

Now, why specifically are the Druze the main component of this Israeli project in southern Syria? In short, the Druze are an ethno-religious group with a significant presence in both Syria and Israel, and Syrian Druze leaders such as Hikmat Al-Hijri, recognizing this Israeli interest, have established, through Israeli Druze leaders such as Mowafaq Al-Tariq, relations with Israeli officials over the past year. These officials, in addition to their geopolitical interests, also have an interest in cultivating the Israeli Druze vote. Within this logic, friction between Syrian Druze leaders and Damascus quickly culminates in Israeli military operations against Syrian Transitional Government forces, as exemplified by the clashes in Jaramana in May 2025 and later in Suwayda the following July. Thus, the current Syrian government finds itself in an extremely precarious position in southern Syria, due to its inability to effectively exercise its authority in the region.However, it should be emphasized that these Israeli actions are motivating the Syrian Transitional Government to seek strategic partners in the security area to act in a way that offers a counterweight to Israeli actions, such as Turkey, already mentioned previously as an important economic and political partner.

The future of Syria? Where are we going?

While post-Assad Syria has made diplomatic progress, seeking to distance itself from its jihadist past while gaining international recognition and economic support from regional actors, it remains entrenched in vulnerabilities and external pressures, beyond its own power struggles within the territory. The Transitional Government still has a long way to go to demonstrate effective governance and internal stabilization capabilities, while simultaneously playing a risky game to balance relations with rival powers.

The Syrian trajectory will depend on a amalgam of factors, which are well-gathered may reveal the ability to transform this still fragile period into a greater solidification of its sovereignty and internal reconstruction. Nine months ago, we concluded our column on Syria on a hopeful note: “The Assad family’s rule marked Syria’s history, and with this chapter over, the hope is that the next ones will be written with less bloodshed.” However, what we see in this revisitation is that the Syrian context is entering a new phase, with a mix of new and old actors. In this sense, although Syria is indeed entering a historical crossroads, marked by possibilities and opportunities, it still faces significant uncertainties about its future.

*Nicolas Zupardo Dutra, undergraduate student in International Relations at the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), member of the Research Group on Strategic Studies and International Security (GEESI-UFPB).

This article is based on information obtained up to September 10, 2025.

References

https://www.syriarevisited.com/p/the-slow-collapse-of-the-syrian-army

https://www.levantine.press/p/tour-de-force-foreign-affairs

https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2025/07/un-experts-welcome-lifting-sanctions-rebuild-syria

https://vizier.report/p/israel-pandoras-box-syria

https://english.aawsat.com/arab-world/5184279-israeli-strike-hits-near-syrian-city-homs%C2%A0

https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-begins-training-syrian-forces-under-new-security-deal