In a speech to German business leaders, conservative German Chancellor Friedrich Merz made remarks that were described by the Brazilian media as ‘praising’ his country, suggesting a return to German ‘pride’ along the lines of a century ago.

At the Trade Congress Summit, held in Berlin on 13 November, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, from the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU), made a speech that reverberated throughout the host country of this year’s COP just one week later. When speaking about how Germany must show that its system is capable of bringing well-being to its population and that democracy is a more attractive system than (growing) autocracy, Merz decided to use the northern city of Belém as a derogatory example to ‘praise’ Germany:

“Ladies and gentlemen, we live in one of the most beautiful countries in the world. Last week, I asked some journalists who were with me in Brazil: who among you would like to stay here? No one raised their hand. Everyone was happy that we returned to Germany on Friday night, mainly because we left that place where we were“1.

Earlier this week, some Brazilian newspapers ran headlines such as ‘German Chancellor praises Germany’, focusing on the first part of Merz’s statement, where he does indeed praise his country. However, this statement is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the German Chancellor’s ‘faux pas’ (which, in fact, are no faux pas at all).

Merz’s statement has not (yet) reached the German public and media. But if it comes to light, it will be just another statement to be rebuked by the country’s current leader. Almost exactly a month ago, Merz sparked a major debate in his country when he made an ambiguous statement against immigrants. At the time, in a press conference with the governor of the state of Brandenburg, the chancellor responded to a journalist’s question about a statement he had made in 2017 about ‘halving the voting intentions of the far-right party, Alternative for Germany (AfD)’. In answering the question, Merz relativised his statement and, after asserting that right-wing populism is a European and global problem, not just a German one, he argued that his government was making great strides in the area of migration, reducing the number of immigrants (referring to refugees, but without specifying). Then he made his ambiguous statement:

“In terms of migration, we have made great progress. Under this government, we have reduced the numbers for August 2024 and August 2025 by 60% in comparison. But, of course, we still have this problem in the urban landscape. That is why the Federal Minister of the Interior is now allowing and carrying out large-scale repatriations. And this must continue“2.

The ‘problem in the urban landscape’ (Problem im Stadtbild), according to Merz, is immigrants. But not just any immigrants. After his comments sparked a debate in the country, journalists tried to get the chancellor to be more precise in his statement and categorically state who the problem he was referring to was. A week later, responding to another journalist who tried to clarify the chancellor’s ‘faux pas’, Merz stated that ‘those who live day to day (in Germany) know that I am right in saying this. It was not the only time I said this, and I was not the only one to say it. There are many out there who say the same thing and who assess the situation in the same way’. He added, responding to the journalist: ‘Ask your children, ask your daughters, ask your friends. They will all confirm that this is a problem. (…) That is why we are going to solve this problem’3.

As much as he avoids being more direct (perhaps to maintain the only apparent difference between his statements and those of the far right), Merz makes it clear between the lines what he means. At a rally in July 2024, while defending permanent controls at German borders, undermining the principle of free movement established in the Schengen Agreements, Merz ‘reassured’ the German public in the state of Saxony, in the east of the country, the second-largest electoral stronghold of right-wing extremists, stating that:

“At the beginning of the week, Markus Söder (Governor of Bavaria) and I made a public appeal for border controls to be maintained. And for them to remain in place until the problem is resolved. And, to be absolutely clear: we will not close the borders again. (…) And our Federal Police and State Police officers, go check if you have the opportunity and want to see it, they have a lot of experience. When they stand there, they know very well which cars are likely to be carrying illegal migrants, where the likely human traffickers are. It’s not you when you’re coming back from holiday. You drive straight through. But those with strange cars, with strange people inside, they are stopped and checked. This kind of control is what we need in Germany, at Germany’s borders, so that at some point we can clean up this problem“4.

Unlike other comments, Merz made a point of ‘leaving no doubt’ about what he meant by ‘the problem’. The statement caused a national uproar, with direct accusations of racism and the use of so-called ‘racial profiling’ (or the act of suspecting a person based on characteristics or behaviours assumed to be typical of a racial or ethnic group) as state policy.

As leader of the conservative CDU party, Merz’s speech was quickly contrasted with that of another prominent figure in the party, who headed the country’s chancellery for almost 20 years: Angela Merkel.

In 2017, the year in which the far-right AfD party entered the German parliament, Merkel, then chancellor of the country, confronted a statement by the extremist party’s spokesperson, which resembled Merz’s current statements, on a public television programme. Jörg Meuthen, from the AfD, said at the time that when he walked through German cities, he ‘could only see a few Germans’. This argument comes from the idea that migrants are ‘replacing’ Germans in their own country. This idea comes mainly as a criticism of the open-door policy conceived, implemented and defended by Merkel at the time of what became known as the ‘migrant crisis’ in 2015. Merkel responded at the time:

“I don’t know what you’re seeing because when I walk down the street, I can’t tell the difference between people with a migration background who are German citizens and those who aren’t“5.

‘Migration background’ (Migrationshintergrund) is the politically correct term in Germany for people who do not look “German” (i.e., who are not white with light eyes and have ‘German’ features). In repeated speeches and appearances at events with groups from diverse backgrounds, Merkel reaffirmed the position of a ‘new Germany’: one of diversity. A society that should no longer be marked by its racist and genocidal past, but rather a welcoming, democratic, and diverse society. This also gives rise to another German term, ‘country of migration’ (Einwanderungsland), something that is normally only used for countries in the New World, such as Brazil or the US.

Merz’s polarising (and sometimes racist) statements contrast sharply with Merkel’s humane and democratic ones. Not surprisingly, many media organisations have spent time discussing the personal intrigues between the two CDU politicians, who represent two very different wings of the party (it is worth noting that Merz left politics when Merkel took over the party leadership in 2005, only returning when she was about to leave power in 2021). But comparisons of Merz’s statements were not only contrasting, but also similar to Germany’s dark past.

For a ‘native German’, it is not uncommon to find someone who was committed to the Nazi cause almost a century ago when looking further back in the family tree. Of course, no one is responsible for the opinions and actions of their relatives, let alone their ancestors. But, as the title of a post on a Jewish blog in 2004 rightly pointed out, ‘the problem is not the grandfather: Friedrich Merz’s strange pride’. That year, Merz celebrated his grandfather, who had been mayor of Brilon, his hometown. At the time, when the Social Democrats won the city’s mayoral election, Merz, then leader of the party in parliament, called for a vote against the ‘red mayor’. For him, it was a ‘deep horror’ that a Social Democrat was at the helm of his city’s city hall and that had to ‘be ended’, associating the rival party’s departure with his grandfather’s victory as mayor of the city in the 1930s. It turns out that Merz’s pride caused some surprise at the time, as his grandfather remained mayor during Hitler’s regime and was a fan of the dictator. At that time, only politicians aligned with Nazi ideology could remain in power (something that even the ‘legendary’ CDU chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, did not do as mayor of Cologne because he opposed Hitler)6, 7.

Twenty years later, Merz continues to attract comparisons with Adolf Hitler’s fans. His remarks about the “urban landscape” prompted many to quickly recall a thought by Hitler’s ideologue, Joseph Goebbels, who wrote in his diary in 1941:

“It is revolting and scandalous that in the capital of the German Empire, 70,000 Jews, most of them parasites, are allowed to roam freely. They not only spoil the urban landscape, but also morality. (…) We must address this problem without any sentimentality“8.

In a country, and especially coming from a generation, confronted daily with feelings of guilt about its past, this kind of ‘similarity’ is rarely a coincidence.

It is a fact that the CDU has moved further to the right since the end of the Merkel era. During her nearly two decades at the helm of the country, Merkel governed in a centrist manner, forging compromises between the centre-left and centre-right. Of course, the party maintained its conservative Christian Democratic stance. But her time at the helm of the country’s government was a period of greater political calm than that which followed her departure. Not surprisingly, one of the country’s largest magazines, Spiegel, even though categorised as more left-liberal, dedicated a recent issue to the feeling of ‘nostalgia for the Merkel era’9. In fact, a recent survey found that about 25% of Germans miss Merkel in government, especially younger people10.

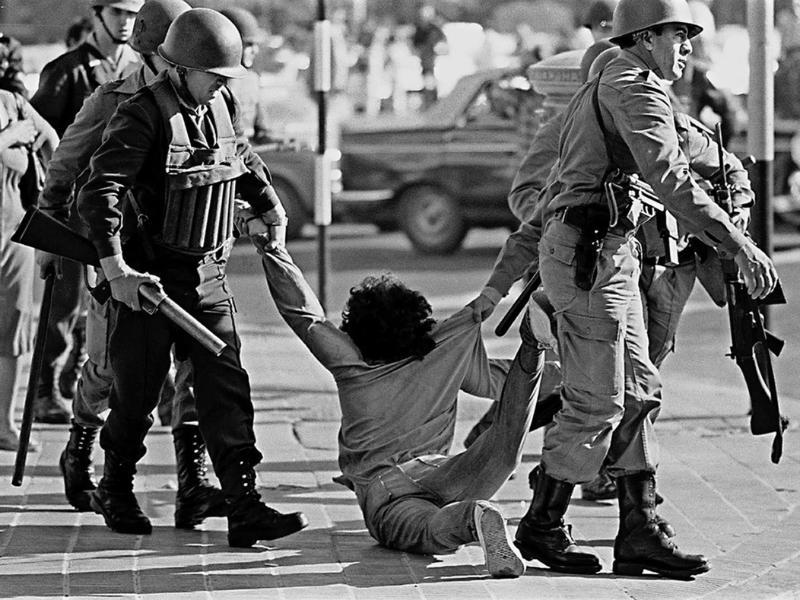

Nevertheless, it is also true that Merkel’s open-door policy in 2015 backfired. In addition to Germany’s structural problems, which prevented the swift processing of millions of asylum applications and the integration of these people into German society (due to a lack of digitalisation, extremely complex bureaucratic processes, and a simple lack of staff to process the applications), the arrival of people who ‘spoil the urban landscape’ or who are ‘a problem in the urban landscape’, to use the terms currently employed, added fuel to the eugenic fire that had been smouldering in German society for decades after the Second World War.

Movements such as PEGIDA (or ‘Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West’) and the AfD (created at the time of the Euro crisis, not the immigrant crisis) gained strength and increasing political influence in the German context. The Merkel era came to an end not in peace and harmony, but in decline and discredit of the people towards traditional political institutions.

The 2021 elections, the first without Merkel in the running, were unprecedented in two decades in Germany because the parties had to, after a long time, truly differentiate themselves. The government that emerged from this election, called ‘traffic light’ because of the colours of the parties leading the coalition, was a weak government, formed by three almost antagonistic forces: social democrats, greens and liberals. With strong sabotage from the liberals, as became clear with the release of internal party documents11, the government became known only for public confusion, which overshadowed the positive policies that were implemented during its three years in office.

It is well known that populists thrive amid political crises. And that is how the AfD managed to rise from fifth place in the 2021 elections (with 10% of the vote, after a 2% drop from the previous election) to second place in the February 2025 elections (now with 20% of the vote).

As in other parts of the world, the centre-right sees the growth of the far right partly as a threat to its own power, as it is competition within its political camp, but also partly as an opportunity for growth, either by ending the need for compromises with the centre or the left, or by ending the need to mask certain interests that were not previously well accepted in society. In the German case, the latter scenario seems to be a strong option for some CDU members, who have either adopted right-wing populist rhetoric in order to grow or have left the party altogether and joined the AfD.

As we saw in Brazil, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Germany, the centre-right has been moving increasingly to the right of the political spectrum, attempting to prevent its collapse and ‘prevent’ the far right from replacing it entirely. However, as seen in these other countries, the scenario is always the same: no matter how much the centre-right adopts populist rhetoric, this type of reaction gives it, at most, a survival of one or two elections. Eventually, the frustrated electorate will tend to abandon the ‘traditional posing as new’ and embrace those who actually present themselves as new. This was the case with the PSDB and Bolsonaro, in Brazil, with the Republicans and Trump, in the US, with the Conservatives and now Farage’s ‘Reform’, in the UK, and the Dutch VVD and PVV. The CDU seems to be following a very similar path in relation to the AfD.

Knowing what is really going on in Merz’s mind, or in the mind of any political leader for that matter, is something that, for analysts, always involves a degree of speculation. After all, we can only analyse the statements and actions of these politicians, without being able to have a frank and open conversation with them about their personal intentions.

In this sense, it is impossible to say (with certainty) where Merz actually stands in ideological terms. What can be said is that, as a conservative German politician, he does not seem to measure the impact of his statements that refer to his country’s dark past, nor does he seem to have a problem making statements that generate a feeling of discrimination against minorities in his country (note that his comments as a long-time politician were not limited to migrants – in general, not only refugees – but also targeted the LGBTQIA+ community and even women).

Analysing his political past and his current actions, and returning to his remarks about Brazil and ‘German superiority‘ (described as ‘praise‘), it is not unrealistic to believe that Merz represents a politician of his time. A post-war German, with family members who shared the same racist and white supremacist views that led Europe to total war and the extermination of millions of people, who, through total capitulation, was forced to ‘learn’ that this type of statement, in public, is ‘ugly’, but that, in private, it can be shared at will. In the middle of the 2020s, when the political world seems strangely nostalgic for the 1920s and 1930s, such figures see an opportunity to bring to light what has remained buried for almost a century, without ever really dying.

The crucial role that such figures play in world politics is not that of revolutionary agents per se, since, to a certain extent, these politicians still maintain a foothold in what has become conventionally known as ‘civilised’ post-Cold War society. Their function, it seems, is to be a rather transitional agent who prepares society for the arrival of what the ancient Greeks already called demagogós, or, literally, ‘leader of the masses’.

As Aristotle rightly said in his book ‘Politics’:

“One type of democracy is one in which all citizens of good birth participate in public office, but the law reigns supreme; in another, anyone who is a citizen can access all public office, but the law governs; but another is one in which everything works, but the mob has the final say, not the law. In this case, everything is decided by popular vote and not by law; and this happens through popular leaders (demagogos). For in democracies where the law prevails, demagogues do not arise, (…) but where laws do not decide, demagogues do arise“12.

Politicians like Merz are not demagogues. They are still bound by the law, whether out of personal belief, inability, or lack of interest in overriding it. Their role, however, whether conscious or unconscious, is to weaken institutions to such an extent that real demagogues can emerge and, from that moment on, it is no longer the law that reigns, but the ‘will of the people’. A will which is not based on principles, but is rather arbitrary, inhumane, and uncivilised. The corruption of democracy, as Aristotle argues, has been observed at various times in history. But apparently, our generation may experience yet another unnecessary episode of this phenomenon.

1 – https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/rede-kanzler-handelskongress-2393818

2 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qE4Ws_jcJPY

3 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDVvrQCdlV8

4 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XdbUs-b7sCI

5 – https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=10155863259214407

6 – https://taz.de/Merz-bejubelt-rechten-Grossvater/!806584

7 – https://www.hagalil.com/archiv/2004/01/merz.htm

8 – https://katapult-magazin.de/de/artikel/ist-der-vergleich-zulaessig

12 – Aristoteles. Politik. Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, 2014. (pg. 186).