Understanding today’s energy transition – the process of “decarbonization”, or the roads to “net-zero” – requires taking into account at how capitalism has historically dealt with its own limits.

One of the central ideas in political economy is that capital is constantly in motion – shifting from money to commodities, from commodities back to money again. And not any type of movement, but an expansive one. As David Harvey1 reminds us, capital’s circulation is “a spiral in constant expansion” – that is, it reproduces as it expands. This is clear when we consider capitalism in history: the expanded reproduction of capital is materially expressed in capitalism’s conquest of increasingly larger areas across the globe, expanding its frontiers to where it had not reached before.

Since the long sixteenth century, capital’s reproduction and accumulation have relied on what Professor Jason Moore2calls the “cheap-nature” strategy, incorporating ever more sources of low-cost labour, raw materials, food, and energy to the reproduction of value – the cheap nature, here mentioned, can be understood from enslaved to ill-paid labour, to colonial extraction of natural resources, to the contemporary exports of unprocessed commodities.

Whenever growth seemed to hit seemingly insuperable barriers, capitalism managed to revive accumulation by creating, in space, favorable conditions for its reproduction. David Harvey explains how spatial processes – from colonisation to urbanisation – serve to absorb capital and labour surpluses in times of crisis, meaning that to “fix” its endogenous crisis, capital also “fixes” in spaces. These “spatio-temporal fixes” then enable the setting in motion of new cycles of accumulation that, beforehand, were constrained and unable to exist.

But what does this have to do with the climate crisis?

One can argue that, today, the climate crisis is the most recent barrier to capitalist expansion. The realisation that there are biophysical and ecological contradictions to endless growth – combined with the refusal of many countries to bear the costs of being the spaces that capital uses to extract unpaid value and generate consumption elsewhere – is putting pressure on the model that historically depended on the almost unlimited exploitation of natural and human resources. The destruction of the planet also raises a structural contradiction to capital’s reproduction, identified by professor James O’Connor3 as the idea that by relying on unlimited growth, capitalism’s expansion undermines the conditions of its own reproduction, by over-exploiting the resource based upon which accumulation is premised.

Yet this ecological pressure does not automatically lead to a shift away from the logic of growth and accumulation. As Professors Brand and Wissen4 argue, environmental crises phenomena can become starting points for new technological and institutional solutions that manage the crisis without resolving capitalism’s underlying contradictions. In their view, international geopolitical tensions that are intensified by the ecological crisis – or new “new eco-imperial tensions” – and the changing competition for global influence are generating selective decarbonization strategies: a transition shaped more by strategic interests than by ecological limits.

In this context, the so-called energy transition, along with the valorisation of forms of natural capital, pertains to the emergence of a new pattern of nature’s exploitation, in which there is an attempted ecological modernisation of production to sustain unsustainable growth.

The last decade unravelled a shift in the discourse of sustainability, in which goals of adaptation, compensation, mitigation, and development became secondary, to be replaced with goals of addressing “green investment” gaps as a solution for the ecological crisis, in what Nelo Magalhães5 denominated the Green Investment Paradigm. Following this logic, by investing in energy efficiency in production processes, substituting resources whose use is environmentally harmful (e.g., fossil fuels), and intensifying the financialization of nature, capitalism would be able to overcome the biophysical limitations to growth.

However, what is, in fact, observed, there is no fundamental transformation in the logic of production appropriation, nor a shift of the energy sources being explored, but rather, once again, an expansion of the frontiers of accumulation to new realms.

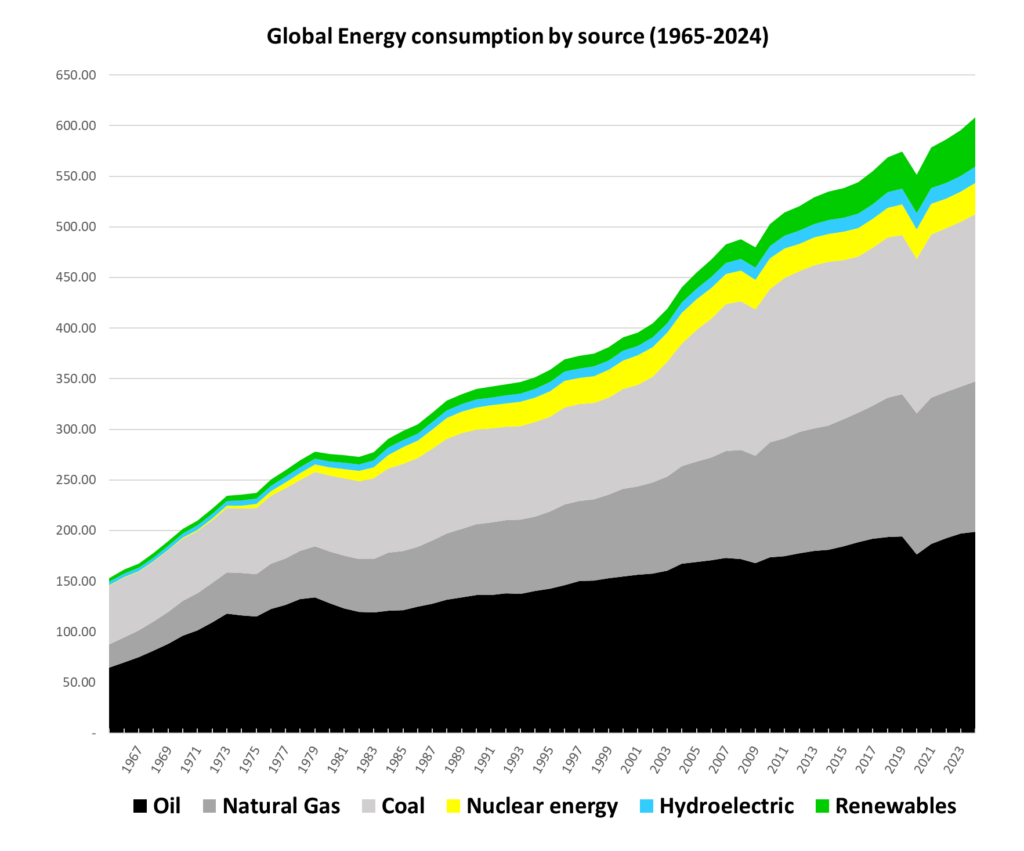

Global energy data tells us the same story.

That is, far from a reduction in energy consumption – or a transition of energy sources – what is seen is the continuous growth in both new and old energy sources.

Except in periods of global economic crisis – oil crisis (1973-1974), global financial crisis (2008-2009) and covid-19 crisis (2020-2021) – energy consumption has always increased. It is evident the large share of oil, natural gas, and coal – that is, fossil sources – despite the increase in nuclear energy, hydroelectricity, and renewables – hereby “clean” sources.

The successive additions are visually clear: regardless of the increase in consumption from renewable and ‘clean’ sources there has been no reduction in overall energy consumption, nor in fossil consumption. Despite differentiated growth rates, the overall trend is one of constant expansion in all energy sources. Renewable sources are being added on top of existing fossil-fuel use, not replacing it.

In other words, the world is consuming more clean energy and more fossil energy simultaneously.

These patterns help shift the discussion from technical obstacles to political ones. The possibilities of any energy transition depend not only on biophysical limits – such as climate constraints or the availability of critical minerals – but also on conflicts among different capitalist groups over who will control the direction of the transition.

As Professor Brett Christophers6 notes, fossil-fuel projects remain far more profitable than many renewable alternatives, and governments still direct substantial subsidies toward oil, gas, and coal. The substantial and continuous investment in fossil fuels creates significant transformational inertia – or rather, ‘fossilization’ of fossil capital.

The political power of these entrenched interests is clear when one considers the conclusions of the Conference of Parties (COP30) in Belém, where no fossil fuel is mentioned beyond the creation of parallel initiatives. Without a major change in regulatory frameworks, the transition will continuously face a paradox, in which:

“to fund the transition to being something else, the oil and gas majors are relying heavily on what they currently are”.

All in all, the ongoing energetic transition is emblematic of the capitalist system’s persistent ability to adapt to barriers to its own development without fundamentally altering its trait of expansive capital accumulation.

While an increase in renewable energy may suggest a shift to different forms of capitalist development, the growth in overall energy consumption suggests that fossil-dependent growth remains dominant and accumulation prevails over transition. This highlights that the shift towards “green” energy resembles an extension of capital’s search for new frontiers of accumulation rather than a true transformation of the global socio-metabolism – that is, of the patterns of energy use and material transformation by specific parts of the capitalist society.

Without substantial regulatory change, a reconfiguration of global power relations and the questioning of why, to whom and for what energy is being consumed at increasing magnitudes, we will only perpetuate rather than overcoming the contradictions of capital’s exploitation of nature.

- David Harvey is a Distinguished Professor of Anthropology & Geography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY).

See Harvey, D. (2014). Seventeen contradictions and the end of capitalism. Oxford University Press, USA.

See Harvey, D. (2019). Marx, capital and the madness of economic reason (Paperback edition). Profile Books. ↩︎ - Jason W. Moore is an environmental historian and historical geographer at Binghamton University, where he coordinates the World-Ecology Research Collective.

See Moore, J. W. (2014). The End of Cheap Nature or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying about “the” Environment and Love the Crisis of Capitalism. In Structures of the World Political Economy and the Future of Global Conflict and Cooperation.

See Moore, J. W. (2016). The Rise of the Cheap Nature. In J. W. Moore (Ed.), Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism (pp. 1–11). PM Press. ↩︎ - James O’Connor was a sociologist and economist, professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC).

See O’Connor, J. (1988). Capitalism, nature, socialism a theoretical introduction. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 1(1), 11–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455758809358356 ↩︎ - Ulrich Brand is a poltical scientist and a professor of International Politics at the University of Vienna. Markus Wissen is a political scientist and professor of Social Sciences at the Berlin School of Economics and Law (HWR).

See Brand, U., & Wissen, M. (2018). The limits to capitalist nature: Theorizing and overcoming the imperial mode of living. Rowman & Littlefield International.

For the concept of eco-imperial tensions, see Brand, U., & Wissen, M. (2024). Eco-imperial Tensions: Decarbonization Strategies in Times of Geopolitical Upheaval. Critical Sociology, 08969205241252774. https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205241252774 ↩︎ - Nelo Magalhães is a post-doc at the chool for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, Paris (EHESS).

See Magalhães, N. (2021). The green investment paradigm: Another headlong rush. Ecological Economics, 190, 107209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107209 ↩︎ - Brett Christophers is an economic geographer who is professor at the Institute for Housing and Urban Research at Uppsala University. See Christophers, B. (2022). Fossilised Capital: Price and Profit in the Energy Transition. New Political Economy, 27(1), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1926957 ↩︎