The year 2026 brought with it the bitter taste of colonialism and military interventionism, especially for the Latin American region, whose 20th-century history still leaves dark traces of authoritarianism.

On January 3rd, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were captured and kidnapped by United States military forces under the aegis of Operation Absolute Resolve. This column will not address the character of the then-former President Maduro, or the quality of his government in the eyes of the Venezuelan people.

Although the episode reignited the debate about “This violates International Law!”, we would need to go back several decades and realize that the game has always been played this way, especially when the main players have veto power in the United Nations.

In major news outlets and on military expert websites, much has been said about the swiftness employed in the operation, which clearly followed a well-defined script to achieve the political objective in question. And at this point, it is worth briefly recalling the teachings of the war theorist Carl von Clausewitz, who, among his postulates in the book “On War,” states that the fundamental nature of war resembles a “Paradoxical Trinity”, whose elements are violence, the game of chance, and rational purpose. Among the figures present in this “trinity” are the people, the armed forces, and the government, and in the case of these last two actors, the dialogue between the government’s rational calculation must be combined with the capacity of the armed forces, in order to translate the political objectives (ends), with the strategy adopted (forms) and the use of tactical operation (means).

Operation Absolute Resolve relied heavily on air power; that is, the US employed power from and through the air. Initially, some more traditional means (equipment) were prominently featured, such as helicopters, 5th generation fighter jets, long-range bombers, command and control aircraft, and aircraft specifically designed for electronic warfare. However, some civilian videos brought the debate to other equipment: drones, specifically kamikaze drones. In a previous column, I specified the nomenclature of drones, as well as their classification according to NATO. (Access here)

Given the hundreds of civilian videos showing US helicopters flying over Caracas without any major problems, it is assumed that the initial phase of the operation involved the suppression (SEAD – Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses) of the Venezuelan Integrated Air Defense System (IADS). To achieve this, the US launched a massive campaign using fighter jets, missiles, and electronic warfare aircraft to “blind” Venezuelan radar systems and command posts.

“As the force began to approach Caracas, the Joint Air Component began dismantling and disabling the air defense systems in Venezuela, employing weapons to ensure the safe passage of the helicopters into the target area,” Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff U.S. Air Force Gen. Dan “Razin” Caine said during a press conference on Saturday. “The goal of our air component is, was, and always will be to protect the helicopters and the ground force and get them to the target and get them home.” Caine also said that “numerous remotely piloted drones” were among the U.S. assets employed during the operation.

Therefore, so far, based on data and open sources, as well as specialized analyses, it is clear that the main means that truly mattered for the US to achieve its political objectives are still traditional equipment, especially helicopters. However, because they are less expensive than cruise missiles, everything indicates that they were used as force multipliers to saturate Venezuelan air defenses.

But what drones were used?

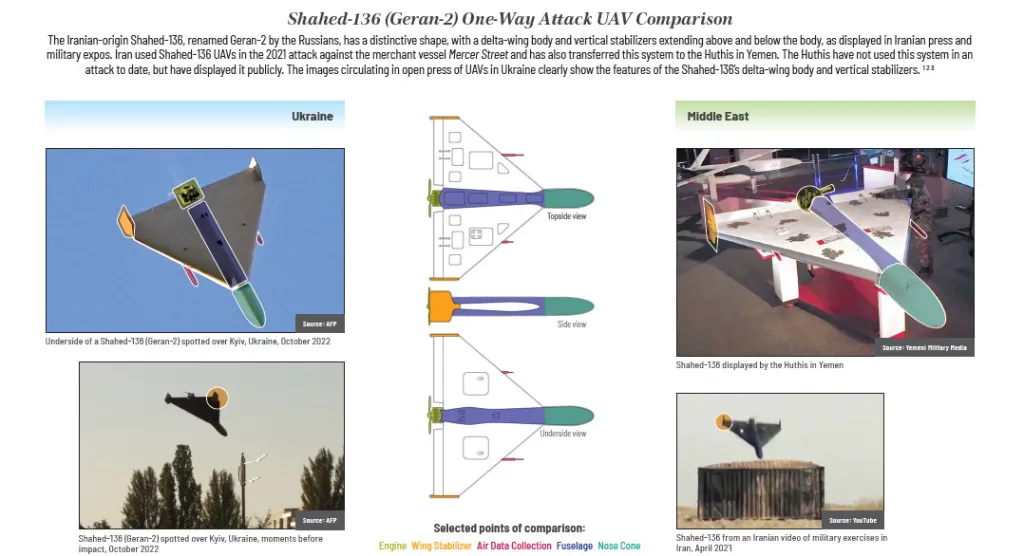

The US has been testing its own version of the Iranian Shahed-136 drone since 2023, which also has a Russian version called Geran.

In December 2025, the US inaugurated its new division for operating these kamikaze drones, which were designated as LUCAS, an abbreviation for Low-Cost Uncrewed Combat Attack System.

Despite maintaining the logic of the lowest possible cost, it is a version that improves some technical aspects compared to the Russian version, such as camera quality and autonomous coordination.

And why does this matter?

Because it shows that the US is beginning to operationalize the use of low-cost drones.

In the early 2000s, Class III drones, such as the RQ-4 Global Hawk and Predator, were important elements in the political and military dominance of the United States, especially in the Middle East, by promoting a distancing between US troops and allies during the Global War on Terror. However, these drones are expensive; for example, the RQ-4 Global Hawk can cost up to $223 million per unit. With more recent experiences, such as the Nagorno-Karabakh War and more recently the Ukraine War, the usefulness and adaptability of smaller drones (Class I and II) for missions previously intended for Class III drones has been observed.

Therefore, what we are seeing now is the US applying lessons learned from observations, and if they employed large drones in the early 2000s, it is important to pay attention to how they will adopt the use of these smaller drones, as they reorganize and reaffirm their place in international security.