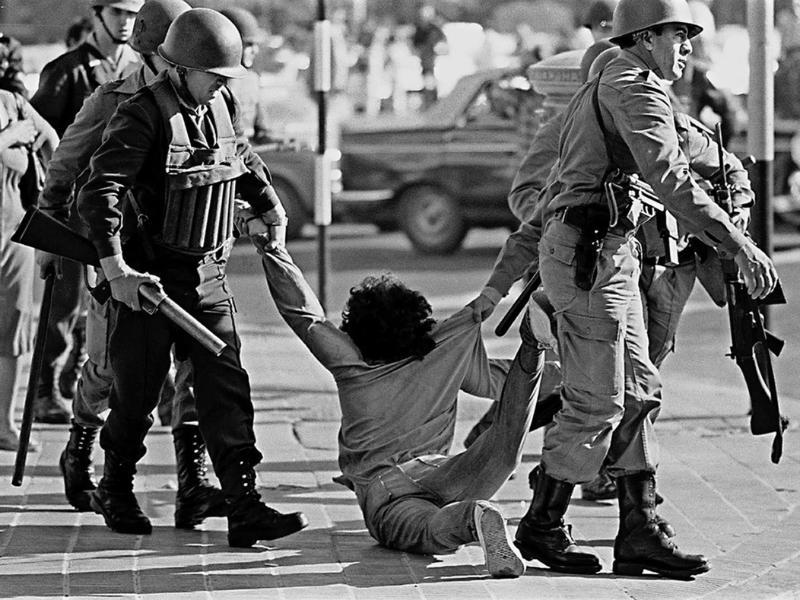

My maternal grandfather, a man endowed with singular historical knowledge and a sharp curiosity about domestic and global politics, began almost all of our encounters with the same warning: one had to be careful when “criticizing the military.” The quotation marks were never gratuitous. My criticisms, from an early age, were directed at the military dictatorship and the practices associated with it, not at the Armed Forces as an institution. Even so, the warning always came.

While other family members, from my grandfather’s generation, let slip a barely concealed nostalgia for the authoritarian period, he appeared wary, almost fearful. We were then living through the beginning of Dilma Rousseff’s presidency, in a formally democratic Brazil that, at the time, seemed to be moving toward becoming ever more democratic. Still, those sharply contrasting reactions—the longing of some, the fear of another—did not sound like distant remnants of a closed chapter. They were, in fact, expressions of a political conflict that was still very much alive.

At that moment, I was not able to grasp the depth of the marks left by the dictatorial experience. Perhaps, even today, I still am not fully able to do so. Nor could I articulate the mechanisms that explain why those marks persist, grow stronger, and endure across decades. Much less could I foresee how they would later be transformed into votes and popular support for politicians openly dangerous to democracy. That understanding came only with time.

This column is about that: the effects of a dictatorial past on a democratic present. More specifically, it is about how values, worldviews, and electoral choices are shaped in people who lived their childhood under dictatorship and their adult lives under democracy. It is also a way of acknowledging that, as almost always, my grandfather was right: the past is not as dead as one might imagine.

The mechanisms of authoritarian inheritance

According to political scientist Anja Neundorf and her coauthors, there are four main mechanisms through which an autocratic past continues to influence political and electoral behavior in democratic regimes.

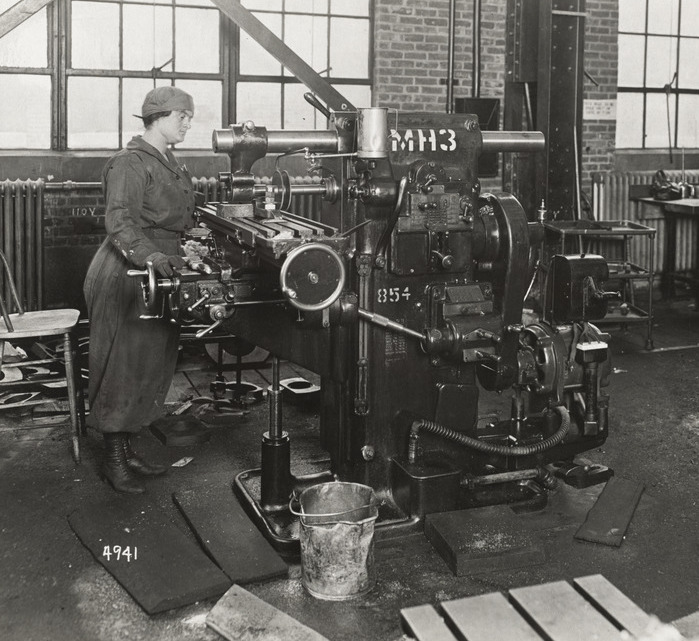

The first is the internalization of norms. This refers to the process by which individuals absorb dominant patterns of behavior—including political behavior—especially when exposed to them during their formative years. Through imitation of parents and the community, the normalization of authority, and, in some cases, explicit indoctrination, those who experienced childhood under a dictatorship tend to reproduce attitudes and values from that period long after its formal end.

But shouldn’t democratic experience in adulthood counterbalance this effect? Generally, no. Values and beliefs formed in childhood encounter less cognitive resistance than those acquired later, when the mind already possesses a broader critical repertoire. Moreover, other mechanisms come into play—especially that of cognitive consistency.

Cognitive consistency, the authors explain, suggests that once individuals adopt core beliefs about political authority and forms of government, they tend to resist information that contradicts them. Revision of these beliefs occurs only when later socialization experiences are strong enough to provoke rupture. Otherwise, individuals filter reality in ways that preserve what they already believe.

When later experiences—economic crises, social insecurity, political discourse—end up reinforcing authoritarian views, the third mechanism comes into operation: contextual reinforcement. In this case, patterns of thought and behavior typical of the autocratic period are reactivated and updated, including political opinions and electoral preferences. It is worth remembering that this reinforcement can occur in any sphere of socialization: family, school, community, city, or even at the national level.

These three mechanisms help explain why facts are so often ignored when they challenge a preconceived worldview and embraced enthusiastically when they reinforce it. Of course, a similar effect occurs even in politically polarized democracies, but not with the same intensity.

The fourth mechanism concerns material expectations. Experiences of security or material deprivation under authoritarian regimes later shape how individuals evaluate the performance of democracies. If the past is remembered as a period of stability—however illusory or selective—frustrations in the democratic present tend to be interpreted as proof of regime failure.

There is also a fifth factor, less explicit but equally powerful: the human tendency to remember the past more positively than it actually was. This is a psychological mechanism of self-preservation, which ends up fusing the memory of the dictatorial regime with the affective memory of childhood. The result is an idealization of authoritarianism—not despite childhood, but because of it.

The past that structures the present

The past, however, does not act only on individuals. It also remains present through institutional channels. This is where path dependency and authoritarian remnants embedded in state structures come into play.

As Paul Pierson argues in his seminal article from the early 2000s, decisions made in authoritarian contexts constrain the options available in the present, even when those options are no longer the most suitable for a democratic regime. Once a particular institutional path is set in motion, changing course becomes costly—whether due to accumulated habits, sunk investments, crystallized rules, or simply because change happens incrementally.

Institutions are not reinvented from scratch; they transform slowly, step by step, starting from previous structures. The more authoritarian the starting point, the greater the number of increments required—and the longer the time needed—for democratization to be completed. Thus, even in formal democracies, traces of the past continue to shape the present.

Is the past inescapable?

The good news is that it is not. The past weighs heavily, but it does not condemn. The very research that identifies the lasting effects of authoritarian experience also points to ways of weakening them.

Studies conducted by Anja Neundorf and other political scientists show that political socialization does not end in childhood—it merely becomes more difficult. In other words, authoritarian values can be unlearned, provided that democracy is capable of offering experiences strong enough to compete with those lived in the past.

This depends, first and foremost, on public policy. Consistent civic education, an understanding of democracy that goes beyond elections and procedures, the teaching of history that does not relativize authoritarian violence, and policies of memory—such as truth commissions, museums, and symbolic reparations—are not identity-driven luxuries. They are long-term democratic instruments. Where the state opts for forgetting, nostalgia finds fertile ground.

There is also a decisive material factor. Democracies that fail to deliver economic security and predictability end up, inadvertently, reinforcing the fourth mechanism described by Neundorf: the biased comparison between a past remembered as stable and a present experienced as chaotic. Fighting inequality, reducing vulnerabilities, and providing social protection is not merely economic policy—it is democratic policy.

Finally, there is the most difficult element to confront: the institutional one. As Pierson argues, democracies inherit structures shaped under authoritarianism and often continue to operate within those limits. Reforming institutions is slow, costly, and politically risky, but failing to do so means accepting that the past will continue to dictate the rules of the present.

None of this produces immediate effects. Democracy offers no shortcuts, no catharsis. It demands repetition, patience, and a mature, conscious understanding of what democracy can and cannot deliver. Perhaps that is precisely why my grandfather distrusted nostalgia so deeply: he knew, from experience, that authoritarianism promises quick order and simple answers to complex problems—but inevitably collapses, and exacts a high price when it does.

References

Checkel, Jeffrey T. 2005. “International Institutions and Socialization in Europe: Introduction and Framework.” International Organization 59 (4): 801–26.

Neundorf, Anja, Natasha Ezrow, Johannes Gerschewski, Roman-Gabriel Olar, and Rosalind Shorrocks. 2017. “The Legacy of Authoritarian Regimes on Democratic Citizenship: A Global Analysis of Authoritarian Indoctrination and Repression.” Working Paper, University of Nottingham.

Neundorf, Anja, Johannes Gerschewski, and Roya G. Olar. 2020. “How Do Inclusionary and Exclusionary Autocracies Affect Ordinary People?” Comparative Political Studies 53(12): 1890-1925.

Neundorf, Anja, Steven Finkel, Aykut Öztürk, and Ericka Rascón Ramírez. 2025. Promoting Democracy Online: Evidence from a Cross‑National Experiment. OSF Preprints.

Pierson, Paul. 2000. “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review. 94 (2): 251–267.