The Proposal

Some topics demand stamina if we want to discuss them with the proper depth, nuance, and authority. Certainly, one of those topics deserving broad space for reflection is China’s current narrative of non-interventionism. Non-interventionism, as the name suggests, is the idea upheld by China, but not exclusively, that relations between countries should be guided not by values that must be defended, but only by economic interests and a certain material positionality. It is within this framework that values such as “sovereignty,” “Right to Development,” “win-win cooperation,” or even very specific visions of “multipolarity” and “South-South cooperation” emerge—or at least develop.

This topic has already been touched on in other columns I wrote for DPolitik (references below), highlighting its importance in the clash of different views on how the global order should or should not proceed. However, I have never faced it head-on due to the natural length limit of columns—too long and interest wanes. So here is the proposal: in this column you are now reading, I begin the discussion of the non-interventionist ideology by presenting its historical context—and largely its justification. Once we grasp the pillars supporting the argument, we can then delve into its operationalization in the modern world. That second part—examining its modern implementation—will be addressed in the next column, allowing us enough stamina to discuss both with the depth they deserve, and ultimately to think for ourselves whether these pillars truly support the argument and whether the argument is preferable to the current order. If the reader agrees with this proposal, let’s begin!

The Historical Pillar: Revolts and Revolutions

It was 1850 when followers of the “brother of Jesus Christ” initiated one of the most devastating revolutions in the history of China and the world: the Taiping Revolution (1850–1864). The revolutionaries had no idea, but this would mark the beginning of the fall of an imperial system that had lasted millennia—something comparable in the West to the Roman Empire if it lasted until the late 19th century.

Years earlier, Hong Xiuquan was preparing for the imperial exams for the fourth time. These exams were established during the Sui dynasty (589–618 AD), formalizing Confucianism as the official state ideology—a process initiated during the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD). While Europe was going through a pre-capitalist feudal period, China had a centralized state bureaucracy organized around an official ideology and implemented through national tests open to all. Hong Xiuquan came from a poor peasant family, so each of his previous three attempts was costly, as preparation required him to give up farm work. This time, he had studied exhaustively and seemed confident.

Unfortunately for Hong Xiuquan—and perhaps the world—his fourth attempt also failed. Unable to tolerate reality, he suffered a nervous breakdown. In his collapse, his desire for greatness mixed with Protestant pamphlets he had recently read, and he had a vision: he was the brother of Jesus and should convert China, thus creating a Chinese Christian state. His mission also had a secondary goal: to destroy the “Manchu demons”—a foreign ethnicity that had ruled China since 1664 under the Qing Dynasty.

Christianity was not new to China. It had been introduced in the 7th century by Nestorian Christians—followers of Patriarch Nestorius, later condemned as a heretic at the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD—and waves of Christian missionaries had come to China from time to time. Specifically, Protestant missionaries arrived as a consequence of China’s forced opening by Western powers during the First Opium War (1839–1842), which we will discuss later. Still, this point is important: the ideology of the Taiping Revolution was a direct product of the First Opium War.

The Society of God Worshippers, followers of Hong Xiuquan, established their capital in Nanjing, renaming it Tianjing (“Heavenly Capital”). During the regime’s existence, deep reforms were enacted: abolition of private property; formal equality between men and women; prohibition of opium, alcohol, polygamy, and gambling; and the creation of a communal land system. These social reforms indicated widespread popular dissatisfaction with the social arrangement and the influence of Western socialist ideals. The bans on opium, alcohol, and gambling were another byproduct of Western influence that had led to the First Opium War.

By 1860, after successive defeats or partial victories with heavy casualties, the Qing army became led by the efficient Zeng Guofan, supported by the “Ever-Victorious Army,” a Western-backed military force seeking stability in China to maximize their investments. Its notable commanders included Frederick Townsend Ward (American) and Charles Gordon (British), nicknamed “Gordon of China.” Both forces finally won in 1864 after a four-year siege. By then, Hong Xiuquan had died of starvation or poisoning (not conclusively known). The victory came at an estimated cost of 20 to 30 million dead.

Just three years after the Taiping Revolution began, northern China also faced critical moments. After the flooding of the Yellow River—interpreted by peasants as divine displeasure or imperial neglect—peasants adopted guerrilla tactics against the Qing forces. Unlike the Taiping Revolution, the Nian Rebellion (1853–1868) had no clear leader or project; it was more akin to a shapeless mass discontented with the imperial government. The Qing sent the famous general Zeng Guofan, and when he failed to contain the unruly peasants, Zuo Songtang was dispatched. Between 100,000 and 200,000 died.

Two years after the Nian Rebellion, the Muslim Rebellion in the Southwest (1855–1873), or Panthay Rebellion, broke out. Du Wenxiu, who experienced being a religious and ethnic minority all his life, being Muslim and Hui in a territory 95% Han and Sanjiao (Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism mix), believed only an independent state could protect his people. For 20 years, his Sultanate of Dali prospered, combining Sharia law, organized civil government, and resistance to Manchu rule. When Qing troops finally entered the fortifications, the massacre was so brutal it became a horror story among survivors.

Inspired by other revolutions—especially the Sultanate of Dali—and the deplorable social conditions caused by the First Opium War, leaders like Ma Hualong and Ma Zhan’ao organized the Uighurs and Turkomans in the Northwest Muslim Rebellion (1862–1878), or Dungan Rebellion. Zuo Songtang crushed this rebellion, leaving behind 5 to 10 million dead.

These revolts and revolutions are usually portrayed in Western historiography as the national element, which combined with the international (which we will soon discuss), produced the fall of the Qing and the imperial system itself. It is notable that many of the political and social elements that created this “powder keg” were Chinese in origin. Still, Chinese historiography views the revolutions and revolts more holistically, understanding that international elements deeply influenced domestic conditions, which in turn fed back into the local manifestations of international factors. In other words, the Chinese do not believe in a strict separation between international influences and national revolts and revolutions. In my narrative, I have tried to showcase at least a bit of both views.

The Historical Pillar: Wars and Imperialism

By 1760, the ingenious English were producing not only mass colonialism but also a revolution in the modes of production: the First Industrial Revolution (1760–1850). Since there is no logical (only moral) reason not to combine these, England’s production surplus was marketed through overseas campaigns, reaching even China. However, by 1792, the situation had changed.

Coming from a recent war that drained public coffers and caused the loss of one of its most productive colonies—later called the United States of America—the English sought a solution in overseas trade. At the time, only the port of Canton in China was open to foreigners, who had to deal with the Hong—a monopoly on distribution and trade arbitrarily regulated by the preferences of the current Hong merchant. To make things worse, the British bought about one-seventh of all tea produced in China and paid with silver. One-tenth of the Chinese state revenue came from the tea tax alone. China’s refusal to buy British goods created an economic deficit in already resentful Great Britain.

Since there is no logical (only moral) reason not to, the British began producing opium in India and trafficking it across China’s borders to reverse the trade balance with a product that creates its own demand. To their credit, the British even tried to negotiate first, sending Sir George Macartney with gifts to the Qing court. Sir George did not bow to Qianlong and tried to negotiate in the king’s language (English), causing confusion. The Qing emperor accepted the gifts and the “vassalage request from King George III.” Lacking the response they confusedly and unskillfully sought, the British had no option but to flood the country with a potent drug.

Opium produced in Calcutta was stronger than Chinese opium and soon sold like water. In 1833, the British government ended the East India Company’s monopoly on the opium trade with China, and nothing like a free market to scale production and sales. By 1835, they were shipping 3.064 million pounds of opium per year to China.

In March 1839, Lin Zexu arrived in Canton, ordered by the Qing emperor to end the opium trade—which was destroying Chinese society from within. Lin arrested thousands of Chinese opium traders, forced addicts into rehabilitation programs, confiscated opium pipes, and shut down opium dens. He wrote a letter to Queen Victoria and, angry at no response, demanded foreigners hand over their opium stocks. When refused, Lin surrounded foreign warehouses, and after a month and a half, the merchants surrendered 21,000 chests of opium. Lin burned the opium with bleach, an amount more valuable than what the British had spent on their army the previous year—a lot of money. When two British sailors beat a Chinese man to death and were sent to forced labor in England as punishment—considered lenient and disrespectful—Lin cut off all food supplies to the British and posted warnings that the water was poisoned whilst ordering the Portuguese to expel all British from Macau.

And what were the Portuguese doing in Macau? Portugal’s history in Macau is one of the oldest and longest-lasting European colonial experiences in Asia. During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1664), Portugal established a trading post on the island, strategically positioned on the Silk Road route. As acculturation of native peoples was common in the Portuguese “civilizing” effort, Macau became an important Catholic evangelization center in Asia. With Hong Kong’s rise in the 19th century, Macau’s strategic importance waned. Competition among Portuguese, Dutch, and British in the region further reduced its importance. But back to the English.

Expelled by the Portuguese and pursued by Lin Zexu, the British fortified themselves on a barren island that would later become Hong Kong. Food shortages forced men to go to the mainland for provisions, but on their return, supplies were seized by Chinese officials. Desperate and hungry, the British started a naval battle, beginning the First Opium War.

The British captured Chusan Island with little bloodshed due to their technological superiority and the weakening of Chinese forces caused by widespread opium addiction. After 600 Chinese killed and 100 captured, Qishan replaced Lin Zexu as the Qing official in charge of resolving the crisis and offered the British 6 million pounds in reparations—a humiliating sum that showed Chinese desperation—plus the opportunity to buy Hong Kong. Ambassadors would be exchanged, the Chinese would stop calling the British a tributary nation, and the British would return all conquered forts and territories. The agreement was so humiliating that Qishan was sentenced to death for treason by the Qing.

After the British captured much of continental China and positioned themselves near Nanjing, a new hurried agreement was made in which China agreed to pay 21 million pounds, open new ports for trade, abolish the Hong monopoly, agree on taxes with the British, cede Hong Kong to the United Kingdom—which would operate under British law—and allow British consulates at ports.

Throughout its millennial history, China has been invaded many times by foreign troops. The Qing dynasty (1664–1912) itself was founded by the Manchu conquest, replacing the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), an ethnically Chinese dynasty that in turn replaced the Yuan (1271–1378) and Jin (1115–1234) dynasties, Mongol and Manchu respectively. Over this very long history, a pattern emerged in which the Chinese believed that even if their enemies achieved military superiority—as happened several times with nomadic tribes in northern China—they would still conform to Chinese customs.

This expectation not only proved wrong against the British but led to devastating consequences. The First Opium War, and subsequent opium wars, opened space for a new type of interaction between the Chinese and foreign powers—a type the Chinese historiography calls the “Century of Humiliation.” Once begun, this new form of relations with foreign peoples continued, as in the Second Sino-Japanese War, where technologically superior Japanese—thanks to the poverty and political instability created by the opium wars and anti-technological Confucianism—committed massacres, rapes, human experiments, and puppet states on Chinese soil.

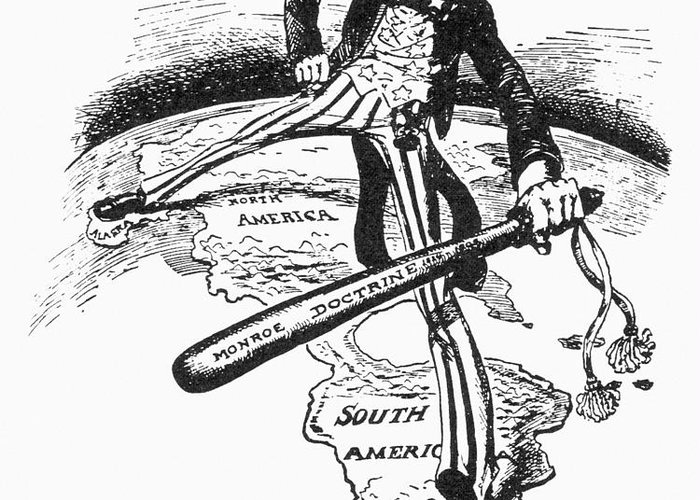

The Chinese experience justified a new world order project, which China can now foster thanks to its recent economic and military power gains. The project I refer to is non-interventionism, because in the Chinese historical understanding, any intervention between powers—even if argued as protection of values or the economy—is fundamentally, or at least partly, a colonial project.

In the next column…

Having understood the historical processes that led to the creation—or perhaps the historical justification—of the non-interventionism principle in the Chinese context, the next step is to discuss the logic of the principle and its consequences for the world order. We will debate whether the historical rationale truly justifies the principle, whether the principle contains contradictions, and whether it is genuinely a better alternative to the present world order. That will be the subject of the next column. See you there!

References

Extra History (2016a, 6 18). First Opium War – Trade Deficits and the Macartney Embassy – Extra History – Part 1. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fgQahGsYokU.

Extra History (2016b, 6 25). First Opium War – The Righteous Minister – Extra History – Part 2. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHmuuc7m1AA.

Extra History (2016c, 7 2). First Opium War – Gunboat Diplomacy – Extra History – Part 3. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jAjUqwauf-A.

Extra History (2016d, 7 9). First Opium War – Conflagration and Surrender – Extra History – Part 4. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9WRmsHFUg0.

Learn Chinese Now (2022, 8 5). All of China’s Dynasties in ONE Video – Chinese History 101. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=Fz_uQNQBK0g&t=890s.

Lieberthal, K. (2004). Governing China: From Revolution Through Reform (2nd ed). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Spence, J. (2012). The Search for Modern China (3rd ed). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Molinero Jr., G. R. (2025, 30 maio). Interdependência e suas promessas vazias. Dpolitik. https://dpolitik.com/blog/2025/05/30/interdependencia-e-suas-promessas-vazias/

Molinero Jr., G. R. (2025, 25 abril). Histórico da segurança energética em um mundo inseguro. Dpolitik. https://dpolitik.com/blog/2025/04/25/historico-da-seguranca-energetica-em-um-mundo-inseguro/