The Argentine Republic finds itself at a political crossroads that could affect its economic future and even the very viability of its water security and territorial integrity. At the heart of this issue lies Law 26,639, popularly known in its country of origin as the Ley de Glaciares (Glacier Law). The subject may seem like a technical or merely conservationist dispute, but the reality is that it is a conflict between the sovereignty and dignity of a people and the tentacles of transnational capital. When Javier Milei’s government proposes to ‘flexibilise’ this protection, the true interest lies in throwing the country’s doors wide open, allowing foreign mining companies to take control over the freshwater reserves that sustain 36 of the country’s 96 hydrological basins, according to data from the Argentine Institute of Nivology, Glaciology, and Environmental Sciences (IANIGLA). Understanding the nuances of this attack requires elucidating the magnitude of what is being offered to the foreign market.

The National Glacier Law, enacted in 2010 following an intense social struggle, established ‘minimum standards’ for the protection of these ice masses. According to Argentina’s official legal framework, glaciers are defined as public goods and strategic water resource reserves. Glaciers function as natural regulators, accumulating snow in winter and gradually releasing it as water during the summer and periods of drought. However, the law goes beyond visible ice and protects the so-called ‘periglacial environment’. This concept, fundamental to science and ecosystem balance, refers to high-mountain areas with frozen soils (permafrost) and rock glaciers. The 2010 law was a landmark of sovereignty because it categorically prohibited mining and hydrocarbon exploration in these sensitive areas, prioritising water over gold and copper.

Alignment with the Global North

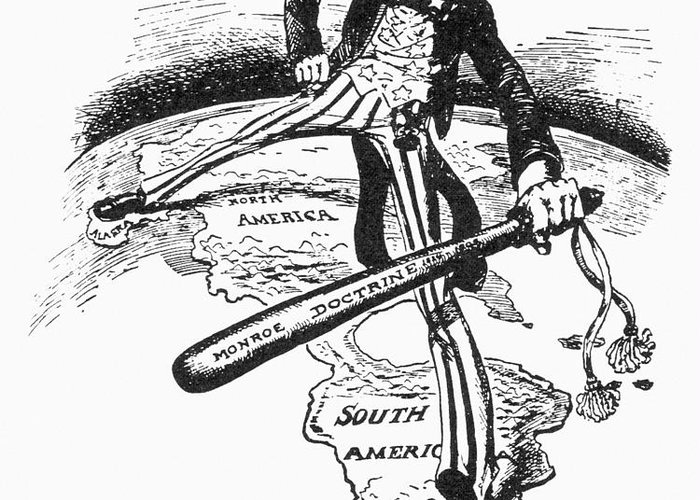

However, under the administration of Javier Milei, this protection is in jeopardy. The government is moving forward with a reform that aims to redefine what constitutes a protected glacier, specifically seeking to exclude the periglacial environment from state safeguards. The motivation behind this change is not scientific, but purely extractivist and imperialist, given that Milei operates in absolute ideological and pragmatic alignment with the Global North, mirroring the rhetoric of figures such as Donald Trump and subjecting Argentine domestic policy to the interests of Washington and major financial institutions. The objective is to transform Argentina into a sacrifice zone for the global energy transition. For the Global North to boast of clean electric cars, Argentina must destroy its mountains to extract copper and lithium. This is the classic imperialist pattern in which the periphery of the world bears the burden of desertification and contamination, while the centre accumulates technology and environmental health.

This entreguismo (handover of national assets) is legitimised by a desperate need for foreign currency to pay an unpayable external debt and to satisfy the fiscal surplus demands of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which acts here as the guarantor of a dependency model. By demanding constant dollars, the IMF pushes the country towards accelerated primary-resource exploitation, with no room for sustainability or long-term planning, as the timetable is dictated by debt instalments. The Milei government utilises the Incentive Regime for Large Investments (RIGI) as a red carpet for multinationals such as Barrick Gold and Glencore, guaranteeing tax exemptions and legal shielding for decades. What we are witnessing is the transfer of sovereignty over the most strategic resource of the 21st century—fresh water—into the hands of shareholders in Toronto or London.

Neoliberal Fallacies and the Resistance Movement

Accompanying this dismantling is the old neoliberal fallacy of promised progress, sustained by the deceitful discourse that mining in glacial zones will generate more jobs and regional development, when, in truth, we know the effect will be the opposite. As repeatedly denounced by Greenpeace Argentina and agricultural labour unions, large-scale metal mining is a capital-intensive activity, not a labour-intensive one. It utilises large-scale machinery and cutting-edge technology, employing a reduced number of workers, many of whom are foreign technicians brought in on a temporary basis. Even more serious is the impact on the existing labour market; by contaminating water through acid rock drainage and heavy metals, mining destroys local agricultural and tourism economies, which are the true generators of sustainable employment for the Argentine people. The progress promised by Milei is a mirage that conceals the precarisation of life and the extermination of traditional livelihoods for the region’s working class.

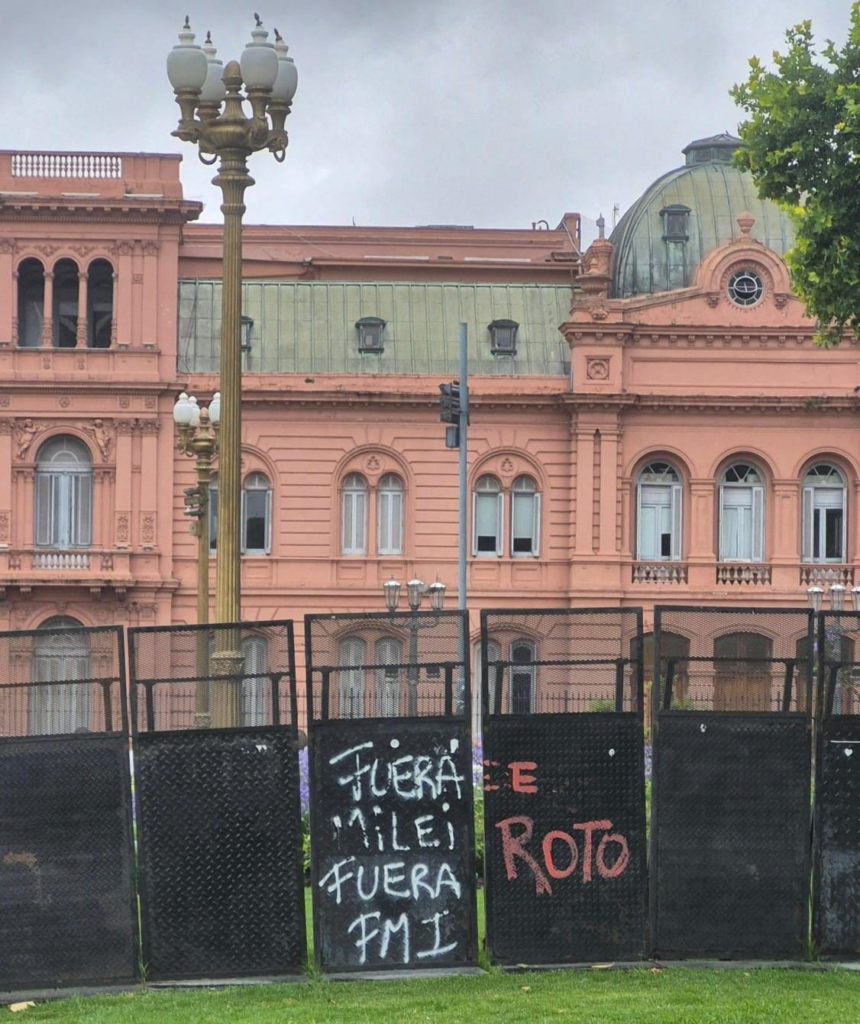

Resistance to this model was not long in organising. On 4th December, Argentina witnessed a day of struggle. Thousands of people took to the streets in various cities across the country, in an alliance between left-wing parties, socio-environmental movements, and territorial assemblies. The cry of “Los glaciares no se tocan” (Don’t touch the glaciers) echoed not only as an ecological demand but as an act of rebellion against fiscal adjustment and imperialism. Protesters denounced Milei’s pact with provincial governors—many of whom have sold out to the mining lobby in exchange for budgetary crumbs—as a betrayal of the nation. These protests demonstrated that the Argentine people understand the direct link between environmental protection and national sovereignty and that no sovereign nation exists without control over its natural assets. A country that surrenders its water to pay debt interest is a country that abdicates its autonomy.

Defending the Glacier Law is, above all, a political and ethical decision; it means rejecting the idea that nature is a commodity to be liquidated by the financial market. Milei’s stance is the ultimate expression of a late and predatory capitalism that prioritises the immediate profit of a mining company over the water supply of an entire population. The exploratory advancement into the periglacial environment is a crime against the nation, as the damage caused by this exploitation is irreversible; it is impossible to ‘restore’ a rock glacier once it has been removed by explosives and excavators.

Safeguarding the original text of the law represents the defence of the working class against the lure of extractivist employability. It is a matter of curbing the Global North institutions that utilise monetary policies to ensure the improper exploitation of natural wealth in Latin America. The mobilisation initiated in December in Argentina must now overflow from the streets into institutional spheres; what is at stake is not just a legal paragraph, but the water security and territorial autonomy of Argentina. Latin American sovereignty is an inalienable asset.

https://www.argentina.gob.ar/ambiente/agua/glaciares/inventario-nacional

https://www.argentina.gob.ar/ambiente/agua/glaciares/ley

https://ianigla.conicet.gov.ar

https://periodismodeizquierda.com/a-milei-le-chupa-un-hielo-los-glaciares-pero-a-nosotres-no/

https://www.tiempoar.com.ar/ta_article/ley-de-glaciares-la-otra-norma-que-milei-quiere-modificar-y-que-pone-en-riesgo-las-reservas-de-agua/

https://noticiasambientales.com/meio-ambiente/lei-dos-glaciares-15-anos-apos-sua-aprovacao-a-luta-pela-agua-os-ecossistemas-e-sua-implementacao-plena/#google_vignette

https://www.greenpeace.org/argentina/blog/greenpeace/la-historia-de-la-ley-de-glaciares-los-glaciares-no-se-tocan/