The discovery of oil on the Equatorial Margin, 175 km off the coast of Amapá and 540 km from the mouth of the Amazon River, has been the new great promise for the state’s economic development. DPolitik spoke to Amapá residents involved in the debate to understand how this is being seen by local politics, how it will impact the community and how decisions are being made.

What is the Equatorial Margin?

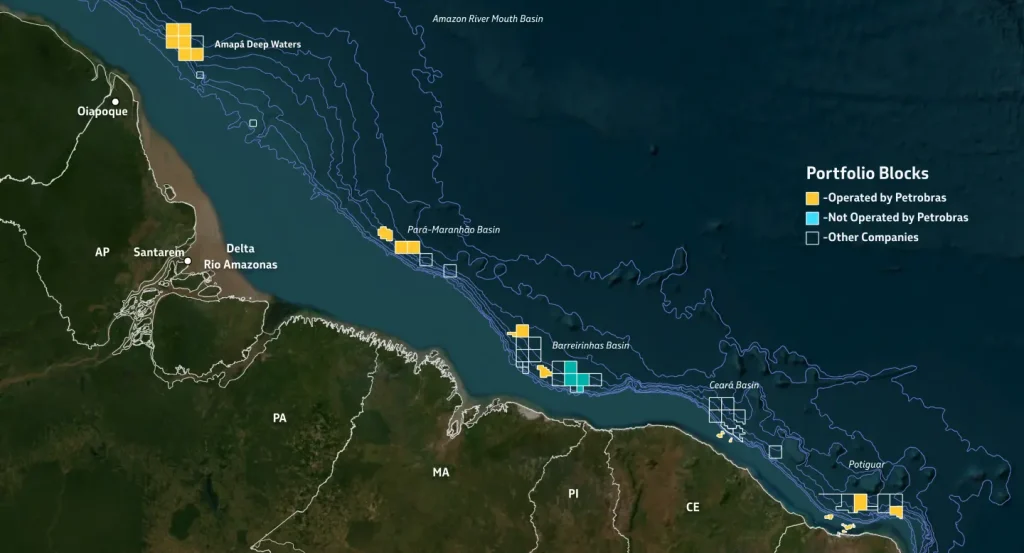

The Equatorial Margin is Brazil’s new oil exploration frontier. It stretches some 2,200 km across the North and Northeast regions, passing along the coast from Amapá to Rio Grande do Norte. There are five sedimentary basins in this area that can store oil in ultra-deep waters: Amazon River Mouth, Pará-Maranhão, Barreirinhas, Ceará and Potiguar.

The first oil well in play is block FZ-M-59, or block 59, which is located in the Amazon River Mouth basin, off the coast of Amapá. The exploration point is 175 km from the nearest point of land and 540 km from the mouth of the Amazon, with a depth of 2,800 meters.

The debate about oil exploration in the Equatorial Margin was ignited in Brazil in 2023, when the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) denied Petrobras an environmental license to drill wells. According to Ibama, inconsistencies in the environmental viability of the project would make it impossible to operate safely in the area.

Petrobras, for its part, has not given up and is continuing its efforts to obtain a license to drill. In two years, the company has adapted to some of Ibama’s requirements, such as the creation of a Fauna Care and Rehabilitation Unit in Oiapoque, completed this year, to care for rescued animals. It also has the support of Amapá’s parliamentarians, who have been mobilizing the state and national agenda in order to make the government’s release possible.

The state government is in favor of exploration and is working with Petrobras to get the environmental license. In an interview with DPolitik, Deputy Governor Antônio Teles Júnior (PDT), an economist and professor at the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP), said that exploration of the Equatorial Margin is part of the state’s development strategy.

“All the regions where there has been oil and gas production have also seen a greater concentration of wealth in those regions. It would be a way of deconcentrating wealth, especially in the North and Northeast,” he says.

The government also has the support of sectors such as universities, like the State University of Amapá (UEAP), which has participated in the debate. The rector of UEAP, Prof. Dr. Kátia Paulino, points out that the scientific evidence of the studies conducted by Petrobras has been positive, making exploration a viable means of boosting the state’s economy. “We are a state that badly needs development. I don’t see oil as the only alternative […] but today it is one of the most significant avenues,” says Kátia.

Last Monday (19), Ibama took another step towards granting the environmental license by approving the concept of the Protection and Assistance Plan for Oiled Fauna (PPAF) for conducting maritime research. The next step will be to carry out surveys and simulations in order to test the ability to respond to accidents.

Promises for the development of Amapá

Amapá is a state with an economy concentrated on the exploitation of natural resources, such as mining and plant extraction. The idea that extractivism will enable local growth is a repeated promise, with examples that have generated questionable results on the economic, social and environmental impact.

In the 1960s, industrial mining used the discourse to encourage the extraction of manganese in the Amapá municipality of Serra do Navio, by Indústria e Comércio de Minérios S.A. (Icomi), a private Brazilian company. The economic activity was seen as a great development opportunity for the then Federal Territory of Amapá, a pioneer in the exploitation of this industry in the Amazon.

Icomi’s operations spanned 50 years, ending in 1997, and left behind an industrial park, a railway and little internalization of the profits generated. Despite the large volume of ore and money handled during the period, the activity was unable to drive local, sustainable development.

The expectation of a productive chain did not materialize. On the contrary, exploitation generated a large concentration of income outside the state. Investment was concentrated in machinery and infrastructure, both of which were not managed regionally, in a movement that had little interaction with the local economy. After the mining company shut down, the town went from model to ghost. Today, Serra do Navio promotes historical tourism from the period o f industrialization, with an economy geared towards the tertiary sector.

In the same way, the construction of four hydroelectric plants has reaffirmed the promise of Amapá’s prominence in the national economy. In addition to not endogenizing profits, the state still experienced a blackout in 2020, which left the population without stable power for more than a month, and to this day has one of the most expensive energy bills in the country. The environmental damage also adds up, given that the construction of the hydroelectric dams has generated impacts such as siltation, responsible for the extinction of the pororoca phenomenon in the Araguari River.

What is being said about the exploitation

Currently, the state of Amapá ranks 25th in the Human Development Index of Brazilian states, according to 2021 data from the Atlas of Human Development in Brazil. Regarding the historical comparison, the government is optimistic: “The exploration of the Equatorial Margin is taking place at a new time. The state will manage the royalties, and this management will finance the diversification of the economic matrix, so that we don’t create a relationship of dependence on oil prices,” says Teles Júnior.

As such, the government is working on three fronts: 1) training the workforce; 2) creating infrastructure; and 3) drawing up a plan for the use of royalties, so that the profits from the activity can be invested in the local economy.

The deputy governor also says that there is no incompatibility between oil and gas production and sustainable use activities in the Amazon, which can be used as a means for local development. Teles Júnior points out that Amapá is at the forefront of the energy transition, and has solar and wind frameworks that will continue to be encouraged even with the exploitation of the Margin.

Civil society, on the other hand, has points of difference with the government. Flávia Guedes, from Instituto Mapinguari, points out the environmental imbalance and impacts not exposed in Ibama’s opinion, such as the effects of exploitation on climate change due to the increased release of CO2. In addition, extraction would be going against the grain of the energy transition highlighted on the national and international scene.

Flávia says that, in this debate, the voice of civil society has not been heard: “It’s as if we were the backwardness of Amapá”. The researcher says that there was only one public hearing in 2023 to discuss the issue, which was not publicized to society. “We were never called by the government for any kind of conversation. Instead of having a dialogue, we had this totally closed environment, trivializing our opinions and the data we brought”, she adds.

This same experience is reported by Glauber Tiriyó, an indigenous leader and law student at UEAP. Glauber says that the activity is presented as a miracle solution, but that it ends up being an imposed process, because there was no dialog with the indigenous people who have demarcated territories in the region, through the Prior Consultation Protocol that should have taken place.

The student also points to the risks of an environmental disaster, which would put the villages located near the Margin at risk. “Where are they going to get their livelihood? It’s my concern, and I believe that of the entire leadership of the region, which does not want to be mistreated by the disaster caused by man himself”.

“Where could the oil issue help us? There’s no way that something that pollutes more can help positively. Either you lose here, or you win here, and from the way the state has been taking us, imposing, it’s the minorities who are going to lose” – Glauber Tiriyó

The debate about oil exploration in Amapá is far from over. The process of granting the license continues, and it will be some time before the activity is carried out and its material returns are observed.

It is a fact that the North of Brazil is a region that is sometimes forgotten by national politics, and that needs incentives for the economy and for local, sustainable development. Amapá, as we have seen, has historically suffered from the extraction of its resources, which are not returned to its people.

Faced with the possibilities provided by oil, and amid the points for and against presented here, it should be noted that the Amazon is not just about its biodiversity and natural resources, but is also a place of people. To understand the Amazon, we need to listen to those who live there, in a complex discussion that must take into account economic, social and environmental factors, considering its various impacts on the different local sectors.

References

https://petrobras.com.br/en/quem-somos/novas-fronteiras

https://www.scielo.br/j/ea/a/Z8KwYg7qrYKsmN4Wc58yCqC/?format=pdf&lang=en

https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/meio-ambiente/noticia/2025-04/petrobras-conclui-unidade-exigida-para-licenca-da-margem-equatorial

http://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/ranking