What once sounded like distant speculation now marks the beginning of a global technological race. In the 21st century, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has established itself as a new “battleground” where nation-states compete for technological leadership alongside geopolitical dominance. While the United States pours massive investment into initiatives like Project Stargate – set to inject up to $500 billion into its AI economy – China advances its strategy of industrial supremacy and state-controlled development.

If the Cold War pitted the US against the USSR through military might, measured in nuclear warheads and rocket propaganda, today’s conflict is quantified in terabytes. Data and algorithms have replaced warheads as the currency of power. The nation that masters cutting-edge AI will wield unprecedented control over the global economy and expand its influence in localised policymaking – potentially resolving conflicts without firing a single bullet. Just as the Soviet Sputnik or the Moon landing proved technological and military supremacy, AI models have become today’s feats of demonstration. The “winner” no longer relies on firearms but on who controls the code dictating the rules of the game.

The US, with its Big Tech hegemony, leads in AI investment. Its strategy blends private-sector innovation with government-imposed restrictions on foreign technologies, such as bans on AI-related semiconductor exports to China. Yet the Asian giant asserts independence from American tech, cultivating sovereign AI systems. Meanwhile, the US cements alliances (with Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea) to monopolise advanced chip production for generative AI training.

In response to sanctions, China has turbocharged its “Made in China 2025” plan, allocating a fresh $47 billion to its semiconductor fund – its largest investment since 2014. State-subsidised firms produce chips while private giants develop closed-ecosystem models. The goal: replace 70% of imported semiconductors, creating a fully Chinese AI supply chain from chips to data.

Might makes right

While the US and China compete in capability, the European Union seeks to establish itself as the digital ethics protagonist with its proposed AI Act – the first global regulatory framework on artificial intelligence. The legislation aims to ban biometric identification in public spaces and other uses deemed high-risk to ethical conduct. The EU’s attempt to dictate moral standards for technology is evident, given the bloc’s inability to match the investment power of the leading AI corporations. Even with robust companies, European budgets remain significantly smaller than those of American Big Tech.

However, this approach may come at the cost of technological relevance. While European bureaucrats debate limits for ChatGPT and other chatbots, Chinese and American counterparts advance military and industrial applications. To reduce dependence on foreign chips and algorithms, the EU has announced partnerships with the UK and Norway to develop AI-dedicated supercomputers. Yet the dilemma persists: how to balance privacy with technological progress amid the US-China showdown?

Other players are adopting strategies to emerge in this contest: India is boosting its AI ecosystem with subsidies covering up to 40% of digital infrastructure costs, according to O Globo’s report. Government support aims to develop national artificial intelligence models applicable across sectors, covering part of the essential computing hardware costs for project implementation. Russia enters the global competition with its GigaChat MAX, which already features among leading AI models, though still trailing Chinese (like DeepSeek) and American (like ChatGPT) frontrunners in international rankings.

Digital Colonies and New Power Dynamics?

When examining the complex dynamics surrounding artificial intelligence regulation, the disparities become clear between nations leading the race and those forced to accept suppliers’ terms to access technological improvements. This landscape is reshaping dependency relations—particularly regarding control of data flows, digital infrastructure, and algorithmic systems that increasingly dictate social and economic life.

Countries lacking full capacity to produce semiconductors or operate supercomputers for advanced AI development risk becoming digital dependents. In this context, governments, public services, and citizens unwittingly feed transnational corporations’ databases while adhering to technical standards set by Big Tech. The result is a new form of subordination—this time, technological in nature.

These “colonies” often become involuntary data suppliers—their information extracted, stored, and monetised abroad. Simultaneously, algorithmic influence reverberates through policymaking: public security protocols, school curricula, and credit systems now hinge on code written elsewhere. All this power rests in few hands. New sovereignty hierarchies emerge gradually through programmed data, while inadequate domestic infrastructure stifles autonomous, sustainable tech policies.

This demands reflection on modern domination and its implications for nations’ foundational pillars. When cutting-edge technologies are primarily imported from the Global North, the Global South remains shackled to foreign systems. Even Brazil—despite strategic partnerships like President Lula’s recent AI agreements with China—retains financial and technological dependence through imported components. If the US frets over Taiwan’s semiconductor dominance, what hope have developing nations in this new technological race?

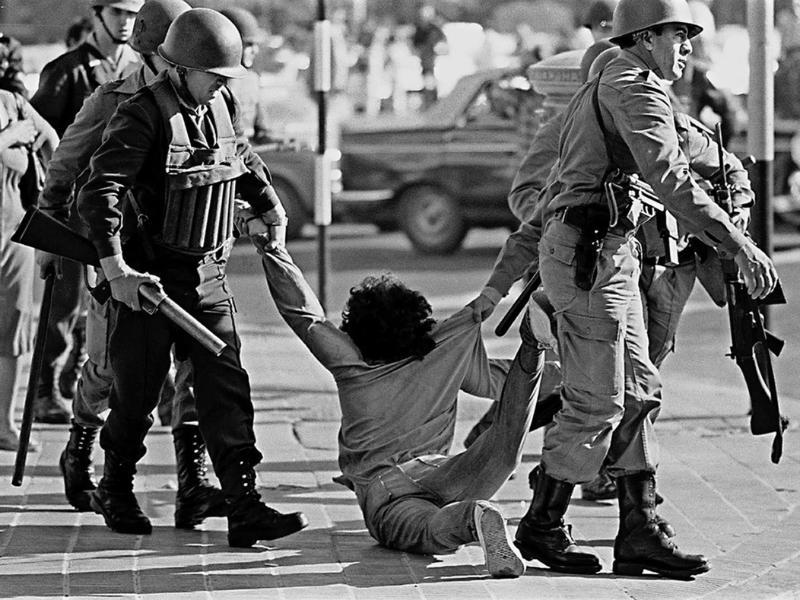

The Militarisation of Data: When Algorithms Wage War

The advent of artificial intelligence has fundamentally altered the nature of conflict, transforming warfare from a contest between rational political actors to one where algorithms determine actions based on operational efficiency. As AI assumes human decision-making roles in military strategy, we witness the rise of a new paradigm – one where probabilities calculated by machines outweigh political deliberation.

Historically, states weighed political and strategic risks before deploying force (with rare exceptions). Today, real-time analysis of vast datasets enables AI systems to directly influence operational calculus – predicting success rates and minimising uncertainties. While this may prevent impulsive actions, it equally facilitates opportunistic uses of force in fragile contexts. The danger lies in creating a paradoxical trap: technology designed to reduce risk may ultimately lower thresholds for military intervention.

The human dimension becomes particularly crucial in conflict resolution. Peacebuilding relies on subjective judgements, moral leadership and nuanced concessions – qualities fundamentally beyond algorithmic replication. As AI displaces human actors, we risk creating technocratic solutions ill-equipped to handle the complexities of post-war reconciliation. The absence of human empathy in peace processes may lead to fragile settlements that sow the seeds of future conflicts.

This militarisation carries profound geopolitical consequences. Autonomous systems could escalate conflicts beyond human control, while algorithmic warfare creates new asymmetries between technologically advanced states and the rest. The international community must confront these risks before automated decision-making becomes normalised in military doctrine.

The New Currency of Power in the Geopolitical Arena

The emergence of artificial intelligence as an instrument of power has redrawn the geopolitical landscape, where sovereignty is now measured by a nation’s ability to develop and control cutting-edge technology. Algorithms and social media platforms wield unprecedented influence – capable of shaping critical decision-making processes and unleashing waves of disinformation through mass-produced deepfakes. At the epicentre of this transformation stand those nations dominating semiconductor supply chains and amassing vast data troves through advanced AI systems. This technological hegemony translates directly into economic leadership and military supremacy, carrying profound potential for global domination.

The militarisation of AI introduces particularly alarming dimensions to this contest. Automated systems now participate in strategic decision-making, enhancing military “efficiency” while eroding the human element essential for diplomatic nuance and post-conflict reconciliation. The concentration of algorithmic power among few actors creates dangerous opportunities for abuse and complicates coordinated responses to unforeseen crises.

Establishing robust, multilateral and ethical international frameworks for AI development has become imperative. The European Union’s AI Act offers a potential blueprint, despite Europe’s limited capacity to compete technologically with the US and China. Effective regulation must serve dual purposes: safeguarding technological sovereignty while promoting global governance structures that protect fundamental rights. Without concerted action, Vladimir Putin’s 2017 warning may transition from prophecy to reality: “Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia, but for all humankind. It comes with colossal opportunities, but also threats that are difficult to predict. Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.”