On its four-decade anniversary, the agreement that started the wave of free movement in Europe is under serious threat today.

Exactly 40 years ago, on 14 June 1985, the leaders of Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands signed an agreement to gradually abolish border controls between their countries in the Luxembourg town of Schengen, where there is a triple border between Luxembourg, France and Germany. The principle of the free movement of people had already been provided for in the Treaty of Rome, which came into being in the 1950s and launched European integration after the Second World War. However, the issue was a major stumbling block between the then ten members of the European Communities.

The free movement of people, however, has been at the centre of integration movements in closer countries for longer. As early as the 1950s, the Nordic countries, which are closely related due to their shared history, had already established the so-called ‘Nordic Passport Union’. Through it, citizens of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Iceland could travel, live and work to and within each other’s territory without the need for any extra documents. In the same decade, the so-called ‘Benelux’ countries (Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg) also effectively abolished the borders between their countries for their citizens.

In this sense, with the embryonic development of what would become, a few years later, the European Union (EU) as we know it today, the Schengen agreement was an almost natural extension for countries that wanted closer co-operation, also with the aim of bringing different European peoples closer together, especially those that still had centuries-old warring factions (i.e. Germany and France).

It’s important to note, however, that Schengen only became something related to the European Union towards the end of the 1990s (what became known as the ‘Schengen acquis’). Until then (and, in practice, until today) European states were free to choose whether or not they wanted to join the free movement zone. Since then, however, countries interested in joining the EU must already prepare to enter the free movement zone.

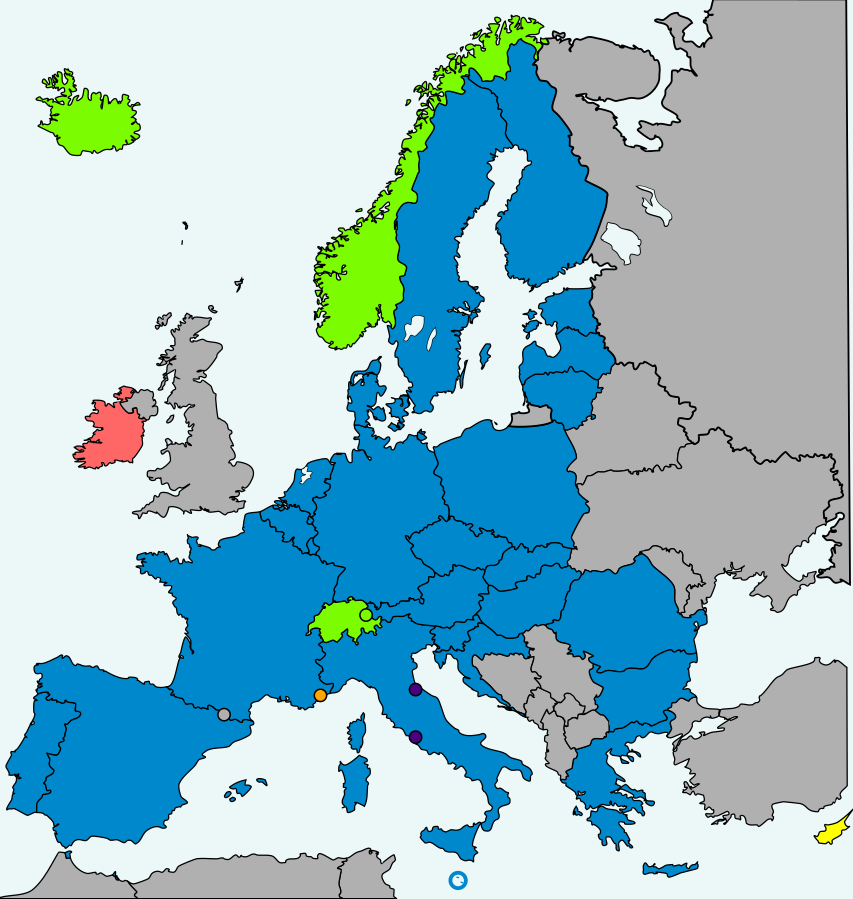

But this development was not obvious. The impasses encountered in 1985 continued over the years, with the result that some countries in the bloc either remained outside the agreement (as is the case with Ireland and the United Kingdom, when it was still a member of the EU) or managed to obtain exceptions to the free movement regime (as is the case with Denmark, which retained the right to maintain border controls). What’s more, other countries not associated with the European Union would also show an interest in participating in the regime, without, however, joining the Union (as in the case of Switzerland, Norway and Iceland). In a few decades, free movement became practically the norm on a continent that for centuries had been characterised by strong nationalism and wars (often based on conquest and control of territories).

■ EU member in Schengen; ■ EU Member State outside Schengen, but with the obligation to enter; ■ EU member outside Schengen; ■ Country outside the EU but in Schengen; ■ Country outside the EU and outside Schengen, but in practice belonging to the Schengen area; ■ Country outside the EU and outside Schengen, but with open borders.

Having become part of what is known in European jargon as the ‘acquis communautaire’, i.e. a matter regulated by the European Union and valid for all its members (with the exceptions noted above), changes to the free movement regime are only made within the framework of the European Union’s legislative procedures, which are in turn regulated by the Union’s treaties. Decisions on the regime are the responsibility of the Union’s de facto legislative houses: the European Parliament (directly elected by the Union’s citizens) and the Council of Ministers (made up of ministers from the member states). The European Commission acts as the body that monitors these measures on behalf of the member states.

The governments of the EU countries could still determine changes to the regime more directly, but only by amending the EU treaties, through a formal meeting of the European Council (made up of heads of government and state), in a complex process that requires unanimity. However, as treaty changes are avoided in practice due to their unpredictability and high cost for countries, Schengen’s internal borders are and (most likely) will remain a matter for the EU alone. Countries that are not members of the European Union but have chosen to enter the Schengen zone, such as Switzerland, Norway and Iceland, for example, have even less chance of changing the regime, since they have no representation in EU organisations (neither in Parliament nor in the Council of Ministers). These countries can either accept or withdraw from the zone.

This is the theoretical view of how the Schengen Zone works. A look at practice, however, gives us a slightly more nuanced interpretation of the regime.

Contrary to what is commonly believed (and published), states still have the prerogative to control their borders within the Schengen regime, however limited they may be.

The most recent document determining the rules for the movement of people in the Schengen regime is the 2018 Borders Code (CFS). In this document, approved by Parliament and the Council, the principle of free movement is maintained, stating in Article 22 that ‘internal borders may be crossed at any place without checks being carried out on persons, regardless of their nationality’. However, it also provides for the temporary reintroduction of controls by member states. This decision is even a premise of the member state in question.

Article 25 of the Code provides for borders to be controlled again, on a temporary basis, in the event of ‘serious threats to public order or internal security’ in a country belonging to the Schengen area. Here, however, we see a first ambiguity. The first paragraph provides for a maximum initial period of 30 days for the reintroduction of controls, but also allows them to last longer, provided there is a ‘foreseeable duration of the serious threat’. This, however, should only happen as a last resort and ‘should not exceed the [period] strictly necessary’ to contain the threat. If, after the indicated period, the threat persists, these controls can be extended for periods not exceeding 30 days.

In total, however, the controls could not last, after successive extensions, more than six months, according to paragraph 4. But the same paragraph states that, ‘in exceptional circumstances (…) this period may be extended for a maximum period of two years’. In other words, until then, a state can unilaterally reintroduce controls of up to a maximum of 30 days, which can increase to 60, not exceeding six months, which in turn can increase to two years…

According to the Code, however, in order to actually re-implement the borders, the state in question must inform the other countries and the Commission no later than four weeks before the controls begin. However, if the threat arises suddenly, this period can be shorter. The information that must be reported is: the reasons for the reintroduction of the border, its scope (indicating where exactly it will take place), duration and also naming measures that other member states can take to help. The Commission has the right to request more information about the reintroduction, but cannot prevent it.

As you can see, it’s not that difficult to reimpose border controls within the Schengen Zone. Even so, considering the entire territory of the free movement area, they are still more the exception than the rule, although the numbers are not as small as you might think.

The European Commission, which is responsible for supervising the internal space, provides a list of cases of temporary reintroduction of borders. What are presented here as ‘individual controls’ are actually cases that have been reported to the Commission. They can be at a few specific crossings or along the entire border between one country and another, lasting from a few hours to several days.

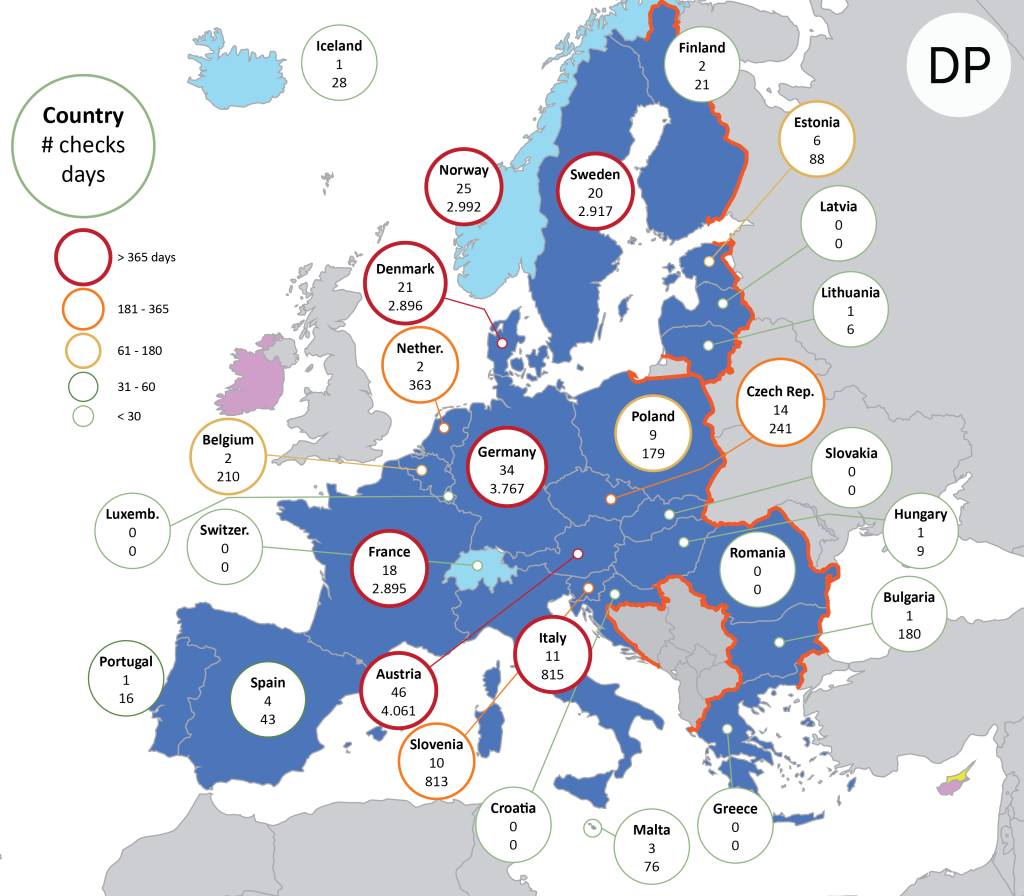

According to the Commission, since 2006, 471 individual controls have been officially registered, with 14 in force at the time of writing. A simple analysis of the document shows that the country that has reintroduced the most border controls is Austria, with 64 reports, followed by Germany, with 50. The table below shows the top 5 countries that have reported the most reintroductions of border controls since 2006.

| Member state | Individual controls (since 2006) | Average duration of controls (in days) |

| Austria | 64 | 78 |

| Germany | 50 | 89 |

| Norway | 43 | 92 |

| Finland | 33 | 22 |

| France | 26 | 140 |

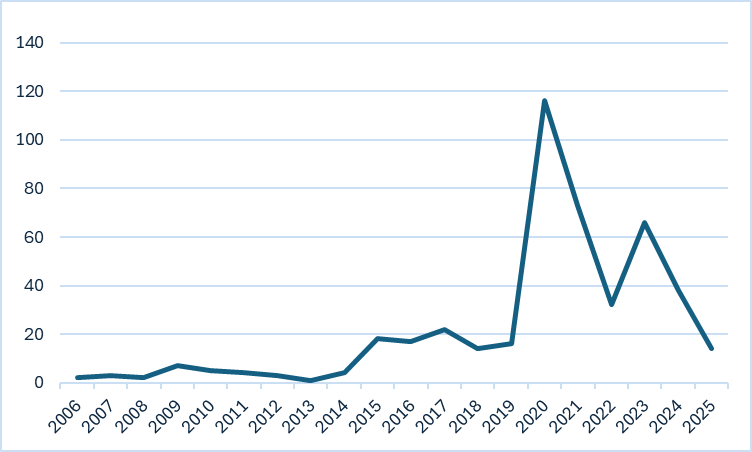

Taking into account all the cases reported since 2006, the average number of controls lasts around 66 days. Since 2014, however, the first year of what has become known as the ‘Refugee Crisis’, this average has risen to 70 days. Per year, there has been an average of 22.8 controls reintroduced, which rises to 35.8 considering only the period 2014-2025 (an increase of almost 60 per cent). It’s clear that the pandemic has had a considerable impact on the data, as most countries have reintroduced restrictions on the free movement regime. However, a considerable increase had already been seen since 2013, when controls went from an average of less than 10 per year to almost 20, as can be seen in the image below.

If we disregard the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, we see that even after the end of the Covid emergency, countries tended to impose more controls, almost six times more than before the 2010s. Another interesting fact, apart from one-off controls, is their duration. The table below shows the five countries where there have been the most border controls since 2014. For this analysis, the years 2020 and 2021 are excluded, since almost all countries introduced controls due to Covid (this being the biggest reason for introducing controls in those two years). It is clear that some countries far exceed the ‘maximum’ period of two years provided for in the Border Code.

| Member state | Individual border controls (since 2014 – excluding 2020/2021) | Average duration of controls (in days) | Total duration of control days (in days) |

| Austria | 46 | 88.28 | 4,061 |

| Germany | 34 | 110.79 | 3,767 |

| Norway | 25 | 119.68 | 2,992 |

| Denmark | 21 | 137.90 | 2,896 |

| Sweden | 20 | 145.85 | 2,917 |

Considering the total duration of days of controls imposed by these five countries, it can be seen that, over a ten-year period, there have been controls on at least one border almost constantly. As you can see from the map below, the countries that impose the most border controls within the Schengen Zone are usually those that are not on the EU’s external borders, with the exception of France and Italy, which have access via the Mediterranean Sea. The champion of border controls, Austria, is located right in the middle of two zones with large migratory flows from outside the EU, the Mediterranean (from Italy) and the Balkans (from Croatia/Slovenia and Hungary).

What is noticeable, especially in countries where controls have been in place for a longer period of time, is that the most common justification given for imposing border controls is the danger of terrorism or the increased influx of refugees. In most countries, however, the justification is some major international event (such as G7 summits, visits by heads of state or international awards). Between 2020 and 2021, the most common justification was the pandemic.

The most interesting thing to note, however, is that the Schengen Borders Code states in its considerations, but not in the articles, that ‘migration and the crossing of external borders by large numbers of third-country nationals should not per se be considered a threat to public order or internal security’. However, this is one of the most common justifications used by Austria, France, Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Norway.

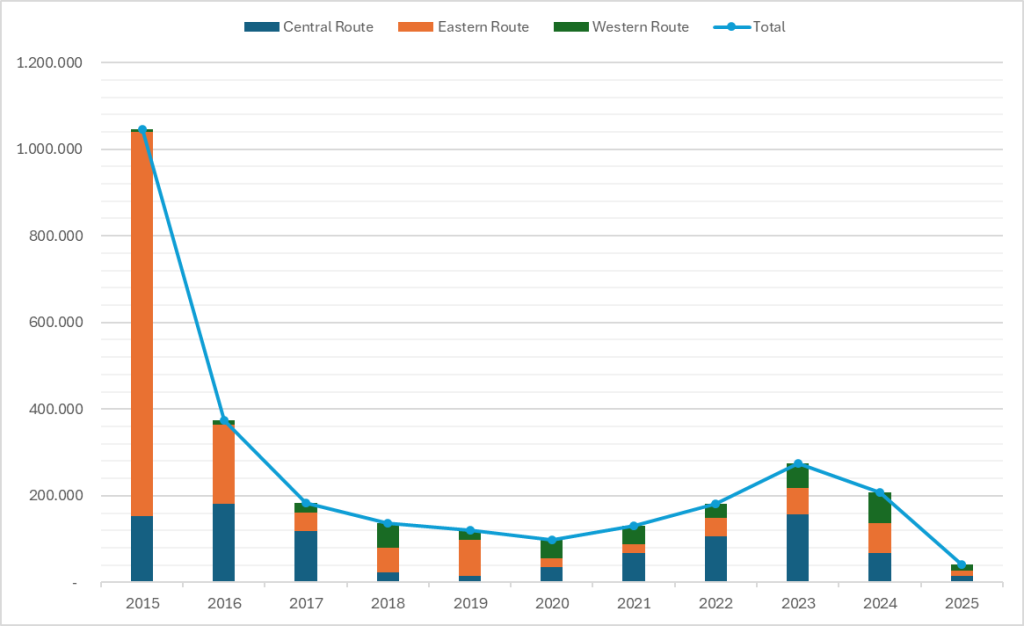

The period that became known as the ‘Refugee Crisis’ saw a massive increase in the number of asylum seekers entering the territory of the European Union (or Schengen Zone) illegally. Data from the European Council shows that in 2015 alone, more than one million people entered European territory illegally, as shown in the image below.

What the image shows, however, is that the number of people entering the free movement regime fell dramatically in the following years, reaching a low of 121,000 in 2019, if we disregard the first year of the pandemic in 2020 (when only 97,000 people crossed the external borders illegally). There was an increase from 2021 onwards, reaching a new peak in 2023 of 275,000 people that quickly reverted to around 207,000 the following year. These figures, however, represent around a quarter of the numbers seen in 2015. What’s more, they seem to be on a downward trend again.

With the war in Ukraine breaking out in 2022 and the economic after-effects left by three years of pandemic, a much bigger problem has taken over the day-to-day lives of European countries: the economy. However, this hasn’t stopped far-right politicians (or those most influenced by them) from continuing to use refugees (or, more globally, ‘migrants’) as a scapegoat for their nations’ problems.

With external and internal effects caused by disagreements in the last German government of the so-called ‘traffic light coalition’, which collapsed at the end of 2024 thanks to the sabotage of one of the coalition parties (the Liberals), the far right has gained strong support, becoming the second-largest force in the German parliament for the first time since the 1930s when Hitler came to power. What’s its biggest banner? ‘Remigration’ of migrants, an extremist concept. ‘Migrants’ is the most commonly used term, which is only ‘better defined’ as ‘illegal migrants’ when a German far-right politician or sympathiser is pressed to define the term. In 2024, however, data leaked to the German press revealed that the far-right party envisages the mass deportation not only of ‘illegal immigrants’, but also of refugees, legal migrants and even German citizens who have a ‘migratory past’1.

The German centre-right, represented by the Christian Democrats, in order not to lose any more votes to the far right, also embarked on a populist campaign using not the terms but the same ideological basis as the far right. There was talk of closing borders2 and even of cancelling German citizenship from people who had naturalised3. In the end, this earned them a few percent more than the right-wing extremists.

The far-right propaganda, supported by the centre-right, had its results. Shortly before the elections, more than 40 per cent of Germans pointed to ‘migration’ as one of Germany’s biggest problems (the same number that pointed to the country’s ‘economic situation’ as a problem)4, 5. The energy crisis, climate change, the cost of living, salaries, pensions and even the Russian threat – all of these issues (Germany’s real problems, by the way) were only seen as major problems by less than 20 per cent of respondents. In the end, however, when a coalition was formed with the Social Democrats, the populist narrative broke down in the formation of a new government, but not by much.

The new German government is getting a bad press among its European partners with its new border control policy, something promised by the candidate (and current chancellor) of the Christian Democrats, Friedrich Merz. However, much his promise of ‘closed borders on day one’ (in a Trumpist daydream) didn’t materialise (since he doesn’t have the power to do so anyway), his new Interior Minister, Alexander Dobrindt, implemented a harsh migration policy that not only imposed border controls on all German borders, but also authorised police officers to expel asylum seekers at the border (something that violates international law, European law and the German constitution). So much so that the government lost a case brought before the German courts in Berlin by people who were expelled when they crossed the Polish-German border by train. The decision resulted in the judges receiving death threats and prompted the Social Democrat justice minister to defend the magistrates6. However, the minister stated that he will continue to maintain the policy of expulsion at the borders, despite the fact that the courts have declared this measure a violation of European law7.

The new German government’s policy has been criticised by European partners, who see the measures as a threat to the Schengen free movement regime. The Luxembourg government had already taken the case of Germany’s proposed policy of indefinite controls to the European Commission in February this year, even before the new policy came into force. However, Luxembourg’s Interior Minister, Léon Gloden, despite strongly criticising the new German policy, said that he would not take the case to the European Court8. The German minister himself, however, stated that he would take the case to the European Court, arguing that his measures are ‘necessary to prevent the advance of the far right’ (while carrying out policies similar to those of the far right)9.

In the neighbouring country of the Netherlands, the right-wing government, sponsored by the extreme right, recently fell because it didn’t go much further with its policies against immigrants. There, foreigners were used as a scapegoat for the country’s housing shortage. In the 2023 elections, ‘migration and asylum’ was one of the most important issues for Dutch voters. Unlike in Germany, however, this issue came after questions of social welfare and fairness10. During the election campaign, Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV party defended the idea that ‘more than 75 per cent of housing goes to foreigners’ and that it was therefore necessary to close the borders so that Dutch people could return to housing (which is not correct)11.

Despite this, the far-right party, the PVV, was elected first in the elections with 23.5 per cent of the vote12. The coalition formed was centre-right to far-right, with the parties VVD (centre-right, of former Prime Minister Rutte), NSC (Christian Democrats), PVV (far-right) and BBB (right-wing populists). As the PVV’s leading figure, Geert Wilders, didn’t prove to be a very tragic leader to be elected prime minister, he remained the most important politician in the coalition, but without receiving the most important post due to lack of support13.

The coalition parties, however, were quite willing to carry out policies and ideas spearheaded by right-wing extremists. With the excuse that foreigners are taking over the homes of Dutch people, a policy was initiated to discourage the use of English as a language in universities in order to sharply reduce the number of foreign students14, even though all the coalition parties (except the PVV) voted in favour of a motion in parliament to ‘keep foreign students and talent in the Netherlands’15. The PVV’s Minister for Asylum, Marjolein Faber, cut half of the NGO VluchtelingenWerk‘s annual budget in order to sabotage aid to asylum seekers already on Dutch territory, which led to a wave of criticism among the country’s politicians and a lawsuit16, 17. In the end, the court ruled in favour of the NGO, stating that changes of this magnitude to the budget can only happen if the situation requiring the budget changes (which is not the case)18.

Unable to implement more drastic measures against immigrants, Wilders withdrew his party from the coalition, causing the government to fall at the beginning of June and new elections to be held later this year19. The anti-immigrant atmosphere, however, never stops with the political forces.

Last weekend, a group of people started conducting border controls between the Netherlands and Germany20. They were even expelled by German police officers who were stopped by the group conducting these illegal controls inside German territory21. When asked about the case, Wilders said that these people are ‘heroes’ and that it is a ‘fantastic initiative’22, while the city council where the group is stopping cars coming from Germany said that it is dangerous and illegal23.

These examples show how free movement on the continent is being threatened by anti-integration political forces. It can be seen that far-right ideas have not only become normalised, but are also becoming (official and unofficial) policy, having repercussions on the lives of European citizens and residents of these countries. With the excuse that foreigners are destroying their countries (be it economic, housing or other more openly racist reasons), supporters of sectarian ideologies are gaining more strength and imposing their ideals that jeopardise a peaceful and united construction that has led much of Europe to its longest period of peace in history. Once again, what we see is that policies designed to destroy institutions and humanistic ideals never start at the highest point, but rather with small actions that gradually become normalised and gain strength. When they reach a state of great strength, they not only become extremely clear, they also become incredibly difficult to stop.

In the case of the European free movement regime, the 40th anniversary of Schengen is marked by a challenge to the concept of free movement, which is facing a threat never seen before.

Schengen Borders Code: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/399/oj/eng

Temporary border reintroduction data: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen/schengen-area/temporary-reintroduction-border-control_en

Migration flow data: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/migration-flows-to-europe/#0

3 https://taz.de/Rassismus-der-CDU/!6060700/

5 https://www.ipsos.com/de-de/meinungsumfragen/sorgenbarometer

9 https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2025-06/dobrindt-europaeischer-gerichtshof-zurueckweisungen

11 https://pointer.kro-ncrv.nl/pvv-overschat-aantal-woningen-dat-naar-migranten-gaat

11 https://www.verkiezingsuitslagen.nl/verkiezingen/detail/TK20231122

12 https://www.rtl.nl/nieuws/artikel/5439953/geert-wilders-geen-premier-van-nieuw-kabinet

13 https://www.rtl.nl/nieuws/politiek/artikel/5475326/kabinet-pakt-internationalisering-aan-studenten

14 https://www.erasmusmagazine.nl/2025/01/22/vvd-nsc-en-bbb-willen-internationale-studenten-behouden/

18 https://nos.nl/artikel/2555815-rechter-minister-faber-mag-subsidie-vluchtelingenwerk-niet-halveren

21 https://nos.nl/artikel/2570415-groep-burgers-houdt-op-eigen-houtje-grenscontroles-bij-ter-apel