In the last column…

In the last column, of the same name but Part I, we discussed the historical events that led to the creation (and the justification) of the Chinese principle of non-intervention. This column functions as a complement, discussing the principle itself. Therefore, without reading the first, this one remains incomplete. Without reading this, the first becomes biased and shallow.

The argument supported by historical pillars

The end of the First World War saw a bipolar world. On one side, the capitalist bloc, led by the United States of America. On the other, the communist bloc, led by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Each bloc produced institutions, rules of conduct in the international sphere, financial systems, and other elements more aligned with their particular worldviews. With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, its institutions, rules of conduct in the international sphere, financial systems, and other elements also fell, enabling the hegemony of the U.S. worldview. In other words, for the scope that interests us, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Charter of the Organization of American States, and the Helsinki Final Acts came to form the global understanding of International Law. Simply put, this means that the hegemonic principle in relations between countries becomes the principle of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P).

R2P is built on three pillars: 1) each state has the duty to protect its own populations; 2) the international community must help states fulfill this responsibility through diplomatic, economic, and technical support; 3) if a state fails to protect its population or is itself the perpetrator, the international community must intervene collectively, including through the use of force, as long as it is authorized by the UN Security Council. As the leader of the new order and hegemon, the U.S. not only gains the capacity to guarantee and oversee the functioning of the R2P principle but also, in numerous instances, to ignore it completely.

Some recent examples where the U.S. ignored the principle are in 1999, in 2003, and since 2014 in Syria. In 1999, NATO, led by the U.S., bombed Yugoslavia for 78 days to prevent Serbian repression against the Albanians in Kosovo without UN authorization. In 2003, the American invasion to overthrow Saddam Hussein, under the claim of weapons of mass destruction — which were never found — was also carried out without UN authorization. In Syria, from 2014 until very recently, the U.S. launched airstrikes against the Islamic State (ISIS) and, in 2017, bombed the Syrian regime after a chemical attack, also without UN authorization. These are some of several possible examples where having power means being able to ignore the rules of the current global order.

The arrival of the 2000s brought with it the development of China in neoliberal molds (and thus following U.S. rules) — even though it maintained a largely technocratic and dictatorial policy. It is argued that China only achieved such development because it was first inserted into and followed the rules of the current global order, under U.S. hegemony. After all, there has been no period in history with fewer conflicts, less global poverty, or greater economic and educational development. Already from the start, the question arises whether the Chinese proposal for a new global order would be capable of maintaining these numbers.

As is common in development history, financial affluence is also translated into technological and military capacity, turning China into a direct competitor of the hegemonic U.S. It is through this gain in capacity that China finds itself in a position to propose such a new global order. Not built on R2P, but on the principle of non-interventionism — justified by its bloody and difficult history with other powers throughout modernity.

The principle of non-interventionism, sometimes translated as the principle of non-interference, was formulated in 1950, just one year after the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party, and since then the principle has been reinforced in Chinese narratives but never substantially altered. For example, in March 2023, Xi Jinping announced the Global Civilization Initiative, a diplomatic initiative to establish a multipolar world order. In it, Xi proposed that countries should “refrain from imposing their values and models on others.” A clear continuation of the 1950 principle.

Elaborating its experience of instabilities and traumas that began in the First Opium War and continued until 1949, the principle of non-interventionism is composed of the following rights: Right to Development; Sovereignty; Mutual Respect; and Win-Win Cooperation. The conciliatory, harmless, and generalist language is intentional, since its goal is to convince populations and decision-makers around the world, gradually overcoming U.S. hegemony in the narrative field.

As proposed by Anne Applebaum, the Right to Development is a legal justification for disregard toward the environment, relying on the debate — this one real — between the need for environmental exploitation by developing economies and the injustice committed by developed economies in ordering the less developed to stop such exploitation. The point is that more developed countries are capable of sharing technology and technique, sending financial support, and producing quotas for the less developed, while less developed economies can find other ways to develop besides the traditional, polluting, and environmentally destructive ones. Put more crudely, if everyone is dead after the climate-environmental crisis, no one will be around to enjoy a good economy.

It is in defense of the Right to Development that the Chinese government supports a number of dictatorial governments, which, according to Geddes, Wright, and Frantz, experts in dictatorships, are the regimes least capable of dealing with the climate crisis. Not only that, but according to the authors, these regimes are also responsible for amplifying the effects of the crisis, such as political and economic instability, increased violence rates, etc.

Applebaum continues, proposing that the elements of the principle of non-interference — Sovereignty and Mutual Respect — are the direct substitutes for Human Rights in R2P. According to the expert, the rights of Sovereignty and Mutual Respect are narrative forms to prevent criticism of any State’s abuses against its citizens. In this way, it would be “respectful” not to intervene when States erode their democratic foundations, when minorities are oppressed, when genocides occur through State action, etc. Finally, Win-Win Cooperation would be the proposition that the international system should be guided by pragmatism, trade that benefits both parties — no matter how vile they are — and not by shared values.

Applebaum understands that the values of the current global order are not perfect. They were imposed and not democratically discussed. They were repeatedly ignored by those powerful enough to do so. Still, as I argued in “Interdependência e Suas Promessas Vazias” (“Interdependence and Its Empty Promises”), the system to judge them and seek reparations exists, and it must be maintained. There is a difference between committing a crime and not being caught, and committing a crime and abolishing the legal system to be able to commit others. An imperfect system of values is better than laissez-faire.

Zhongying Pang adds to the debate by offering three practical reasons for maintaining today the principle created in 1950 by a China quite different in many aspects. According to the author, the principle of non-interference: 1) protects China from current influences that recall its traumatic past, while protecting the current government against reprisals for its actions in Tibet, Xinjiang, Taiwan, etc.; 2) the narrative brings China closer to various countries with a similar traumatic past, and even to countries still fighting colonialism today; 3) justifies Chinese inaction in cases where acting would be costly or difficult.

Of course, the Chinese government has done more to promote the principle of non-interventionism beyond the narrative field. The BRICS as a parallel forum to the G7, influence in regional economic blocs, massive and unparalleled investments in Africa are some examples of political and economic actions taken by China in the hope of making its worldview real.

The Erosion of the Historical Pillar

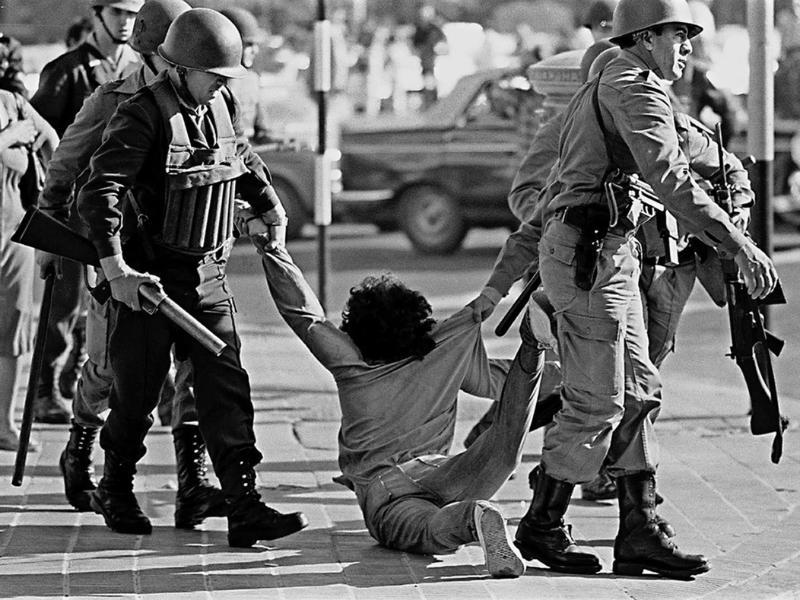

If in the last column I dealt with the historical events that justify the narrative of the principle of non-interventionism, now we analyze the historical events that call it into question, starting with China’s involvement in the Korean War (1950–1953). In October 1950, shortly before the emergence of the principle of non-interference, but still recently after the history used as justification for the creation of the principle, China entered the war with the “People’s Volunteer Army,” a name that indicated, or sought to indicate, that the action did not officially come from the Chinese government, but rather from civil society — avoiding a direct conflict with the U.S. and positioning Chinese society as “sister” to North Korea. The Chinese intervention of thousands of soldiers led by General Peng Dehuai had as objectives to defend the national territory (the UN forces, led by the U.S., pushed the North Koreans to the Yalu River — the border between North Korea and China); to support the communist regime in North Korea; and to affirm China’s position as a communist power, thus consolidating its influence also at the domestic level (the communists had taken power in 1949, still very recent).

In other words, the Chinese intervention in the Korean War just months before the creation of the principle of non-interference shares the same history that is used to justify the principle, and yet produces the opposite effect. Here a factual element is opposed to the narrative: when two of the three reasons offered by Zhongying Pang for non-intervention end up actually calling for intervention — namely 1) to protect China from current influences that recall its traumatic past, and 2) to narratively bring China (through communism, in this case) closer to other countries — China will carry it out.

One example does not disprove a trend, the reader might argue. So let us look at others.

For the Vietnam War (1955–1975), China sent 320,000 soldiers in non-combat roles, such as road construction, railways, and anti-aircraft defense systems. Besides logistical, technological, and technical support to North Vietnam (communist, led by Ho Chi Minh), Chinese intervention also occurred through financial and material support, for example, sending weapons, ammunition, food, uniforms, and fuel. Besides its intervention in wars during this period, China also politically supported various communist revolutions in several countries in Asia and Africa.

In 1982 China officially declared its “Independent Foreign Policy for Peace,” which significantly intensified the principle of non-intervention, elevating it to the status of an official declared foreign policy. One might imagine that intervention cases then ceased, but no. China became the second largest troop contributor to UN actions among permanent members of the Security Council, the thirteenth country worldwide. It has mediated international conflicts where the U.S. would not be welcome, such as the mediation of Iran-Saudi Arabia relations in 2023. As Harris reports, in 2021 China led investments in Africa — $254 billion, while the U.S. invested $44.9 billion at the same date — investments that translate into infrastructure, logistics, and everything necessary to maintain the regimes China supports in Africa (something I elaborate on in “Interdependence and Its Empty Promises”).

All these counterexamples, and others I could give, point to the same conclusion: just like the U.S., China will follow the institutions, international conduct rules, financial systems, and other elements it creates until these become contrary to its interests. When that happens — or as said before, when two of the three reasons offered by Zhongying Pang for non-intervention end up actually calling for intervention — China will act as a hegemon.

This is also due to the functioning of the international system itself — the arena where interactions between countries occur. As authors like Waltz and Mearsheimer propose, just as the market produces the price of a product independently of the choices of individual companies, the international system produces incentives and barriers that effectively limit the possibility of choice by states. It is clear that, just as in the market more influential companies have greater leeway, more powerful states also have more freedom of action. In the end, however, the system dictates that powers act as powers.

Knowing that powers will act as powers, regardless of the principle they promote, one question remains for the rest of us who are not citizens of global powers: which principle should we follow? The answer I propose is that the supposed duality in the question is a false duality.

Can We Learn From History?

The competition between the U.S. and USSR during the Cold War produced a series of developments in the global order proposals of each of these states. The U.S., criticized for inequality, racism, and exploitation in the capitalist system it proposed, ended up being forced to invest in the social aspect, promoting Welfare Systems worldwide, labor rights, unions, social movements such as the Civil Rights Movement of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., etc. The influence of the competition with the USSR helped economically develop various countries that used the rivalry for influence as an advantage in negotiations, and ultimately Human Rights came to include Civil and Political Rights of peoples.

On the other hand, competition with the U.S. forced the Soviet regime to invest in other countries to model a “perfect regime.” Within the USSR itself, U.S. pressure produced improvements in health, housing, and production. Ultimately, Human Rights came to include Social and Economic Rights.

This is just one example of the dialectical character that competition between different ideals or principles for a global order can have. As happened in the past, both propositions can suffer a synthesis or at least influence improvements in their respective principles. This is not to say that this dialectical movement will in fact occur, but rather that it should occur. For this, it is the duty of each state participant in the international system, according to its capacity, to pressure as much as it can so that perhaps we may reach a more equal and just system.

References

Applebaum, Anne. (2024). Autocracy, Inc.: The Dictators Who Want To Run The World. Random House: USA.

Fernández-Villaverde, J., Ohanian, L. E., & Yao, W. (2023). The neoclassical growth of China (Working Paper No. 31351). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspectives on Politics. 12(2), 313–331.

Harris, J. [johnnyharris]. (2023, July 26). We’re heading into a new Cold War [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=72m0cK423-Q

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001). The tragedy of great power politics. W. W. Norton & Company.

Molinero Jr., G. R. (2025, 30 maio). Interdependência e suas promessas vazias. Dpolitik. https://dpolitik.com/blog/2025/05/30/interdependencia-e-suas-promessas-vazias/

Molinero Jr., G. R. (2025, 25 abril). Histórico da segurança energética em um mundo inseguro. Dpolitik. https://dpolitik.com/blog/2025/04/25/historico-da-seguranca-energetica-em-um-mundo-inseguro/

Pang, Z. (2009). China’s non‑intervention question. Global Responsibility to Protect. 1(2), 237–252.

Waltz, K. N. (1979). Theory of international politics. McGraw-Hill.