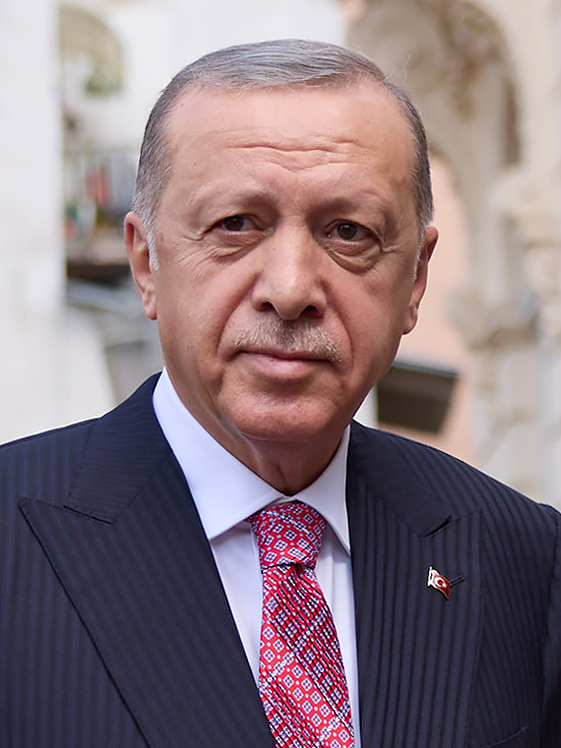

Last Sunday (28/05), Turks went to the polls for a polarised second round. On one side, the well-known Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has been in charge of the country since 2003. On the other, an opposition candidate who presented himself as the democratic option in this election that seemed more like a referendum than an election. Since 7pm in Ankara, Turkey’s capital, Erdoğan was declaring that he had once again won the elections. On Monday’s morning (29), the results of the vote counting at 99.85% were as follows:

Erdoğan (AKP) Erdoğan (AKP) |

Kılıçdaroğlu (CHP)  |

| 52,16% 27,725,131 votes |

47,84% 25,432,951 votes |

But what does this mean for Turkey? And for the world? Below, we summarise for you what Erdoğan has represented and represents for his country and the world.

Erdoğan (pronounced “uh·duh·wan“) has had a long political life. He has been involved in politics since 1976, when he joined an anti-communist and an Islamist group, growing up in there. At the age of forty, in 1994 he was first elected mayor of Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city, after failed attempts for parliament and smaller mayorships. With about 25% of the vote at the time, Erdoğan went on to run Istanbul without being taken seriously by the media and his opponents. However, he used his position as mayor in a pragmatic way. With policies aimed at solving water shortages, pollution and traffic problems, he became popular. To further win over the people, Erdoğan made his own email address available and opened new municipal phone lines so that people could contact him more easily. In a 2003 article, the New York Times published an article talking good about “the Erdoğan experiment” (open), where it is stressed that as much as he was a devout Muslim with an “Islamist past”, he had transformed himself into a “modern, pro-Western democrat”.

His tenure was interrupted before its end at the end of 1998 because he was sentenced to prison for reciting a poem, adding verses that said “the mosques are our tents, the domes our helmets, our minarets (mosque towers) our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers“–parts that were not in the original version of the poem. This was seen as an incitement to violence and religious and racial hatred by the Turkish judiciary at the time. Erdoğan was then sentenced to 10 months in prison, later decreased to just four. A ban on participating in parliamentary elections was also imposed on him.

The former mayor of Istanbul had difficulties in sticking to one party during his political career before 2003. Constantly, the parties to which he was affiliated were either banned by the army or by the courts.

It is worth noting here that Turkey’s recent history observed a strong turn a la the West in the first half of the last century. With President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of the Republic of Turkey, founded in 1923 with the end of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, a policy was introduced that became known as “Kemalism“. Of the six principles that this ideology preached, “secularism” is one that is important to stress here because, unlike other countries, Turkey went from being a Muslim country to one in which religion should be totally separated from all public spheres, including politics, justice, education and society. This point is especially important for Erdoğan’s story.

The interest of the former mayor of Istanbul and his allies was precisely that of a party with an Islamic slant, which was constantly blocked by the country’s authorities. So they chose pragmatism in forming a party that would be more “classically” conservative, without so much of a religious slant. Thus, in August 2001 the “Justice and Development Party” (abbreviated in Turkish as “AK PARTİ” or just “AKP”) was created under the leadership of Abdullah Gül – also an Islamist – and Erdoğan. This became the “home party” of the former mayor of Istanbul from that moment on.

In the 2002 elections, Erdoğan ran ahead of his AKP party and secured just over 34% of the vote nationally. However, his ban from politics due to the 1998 sentence was still in place. Thus, Gül had to take over as prime minister of the country in his place.

• AKP (34.28%) | • CHP (19.39%) | • DEHAP (6.22%)

Source: Wikipedia

It did not take long for the party, with help from the second most voted party–the “Republican People’s Party” (CHP) which had about 19%–the government managed to remove Erdoğan’s political ban, which enabled him to participate in an election that had to be repeated in 2003 in Siirt province (where Erdoğan declared the poem that earned him four months in prison) due to irregularities. Thus, the former mayor of Istanbul won a seat in parliament and could take over as prime minister–with Gül going to a government ministry.

In the upcoming 2007 elections, the vote that was supposed to take place later that year took place in July, after the Turkish parliament failed to elect a new president for the country–in Turkey, at the time, the president was only the head of state and not of government, as in Portugal or Germany, for example, and was elected by the parliament, not directly as in Brazil or the US. In April of that year, 300,000 people protested in the capital Ankara against the possibility of Erdoğan running for president, fearing that he might have more influence to reverse the country’s secularism. The election, however, was a success for the AKP, which went from 34 percent of the vote to 46 percent. Erdoğan, who had announced that his party would nominate ally Abdullah Gül for the presidency, remained in the post of prime minister.

• AKP (46.58%) | • CHP (20.88%) | • MHP (14.27%)

Source: Wikipedia

The deadlock over the election of a new president, however, continued. This led the AKP to propose a referendum that sought to change the constitution by implementing a direct vote for president, shortening the term of office from seven to five years and allowing the incumbent to run for re-election. The “yes” vote won by 68.95% in October 2007.

These victories, however, did not mean less friction. In March 2008, Turkey’s attorney general petitioned the country’s Constitutional Court to ban the AKP on the grounds that the party had become active against Turkey’s secularism. “The risk has been growing every day (…) The danger is clear and concrete”, the prosecutor argued in his petition to the Court¹. In society, there was fear that the AKP intended to impose Sharia law–the “Islamic law”, by which all laws are founded on the Koran, the Muslim holy book. This fear was not without foundation, as the party had tried to remove the ban on Muslim women wearing veils in universities, which was seen as anti-constitutional in the country. The Court, however, rejected the prosecutor’s request² and the AKP was allowed to continue existing.

A new referendum in 2010 proposed changes to the constitution that were intended to bring it more in line with the requirements imposed on Turkey’s application to join the European Union (EU). The changes did not have the majority needed to pass parliament, but the numbers of parliamentarians made it possible for a vote to be held by the people. The ruling AKP backed a “yes” vote, while the opposition, however much it agreed with parts of the reforms, backed a “no” vote, saying the judiciary and army would have less power and this could put the country’s secularity at risk. With the yes vote passing with almost 58% of the vote, Erdoğan counted this as another victory of his. Empowered by this result, the AKP promised to create “a new constitution” after the 2011 elections. On June 12, Erdoğan’s party grew by another three percentage points, winning 49.8 percent of the national electorate. The constitution, however, remained unchanged.

• AKP (49.83%) | • CHP (25.98%) | • MHP (13.01%)

Source: Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi

Before the next parliamentary elections that would take place in 2015, Erdoğan was nominated by his party to the post of president. In August 2014, and after changes were made so that the office of president would be decided by direct vote of the people and no longer by parliament, he was elected with 51% of the vote in the first round.

• AKP (51.79%) | • CHP-MHP-other coalition (38.44%)

• HDP (9.76%)

Source: YSK

Even if the presidency was most representative, Erdoğan stated after winning that he would not respect the neutrality that was expected of presidents as head of state. With his party continuing to lead parliament–with almost 50% of the vote in the second parliamentary election that took place in 2015–the scenario was seen in which Erdoğan would rule the country through the prime minister appointed by his party in parliament, while he would represent the country to the world in his new position as president. The next two years were more tumultuous for the country.

On 15 July 2016 a part of the Turkish Armed Forces attempted a coup d’état to unseat Erdoğan. Justifying their actions on the erosion of secularism, democracy and human rights, the military tried to take over Istanbul, Ankara and especially the bridge connecting the European and Asian part of Turkey, the Bosphorus Bridge.

The coup failed, as most of the country’s military forces remained loyal to the government and defeated the coup plotters. The toll was 300 dead and more than 2,000 wounded. Government buildings were bombed during the attempt. The government’s reaction to this coup attempt was severe. 10,000 soldiers and almost 3,000 judges were arrested. 15,000 education workers and 21,000 teachers had their licences suspended by the government on charges of being accomplices. More than 77,000 other people were arrested and 160,000 lost their jobs in retaliation. The following year, the time came for a new referendum.

This time, the AKP proposed changing the country’s regime, making Turkey a presidential republic rather than a parliamentary one. The post of prime minister would be abolished, parliament would grow from 550 to 600 seats and the president would have more powers in appointing judges and prosecutors. Following the vote on 16 April 2017, the country’s electoral authority, the Supreme Electoral Council (YSK), ruled that ballot papers that did not have the official stamp would also be counted as “valid votes”, which was criticised by many as an illegal move as around 1.5 million ballot papers would not have the stamp. Protests followed. In this scenario, the “yes” to the proposal garnered 51.4 percent against 48.5 percent of the “no” votes.

After the referendum, in 2018, Turkish voters went to the polls to elect their president again. Erdoğan increased his percentage and was re-elected in the first round with 52.59% of the vote. This is Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s electoral summary until the 2023 elections.

• AKP (52.59%) | • CHP (30.64%) | • HDP (8.40%)

Source: YSK.

Turkey may not appear every day in the news in many countries, but it is a very relevant country in several issues of the international community. Its geographical position, between Europe and Asia, summarises well its relations with the world, especially under Erdoğan.

Firstly, Turkey is a member country of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation – NATO. As such, it is officially allied with the West. This means that even though it doesn’t have its own nuclear bombs, for example, it has the right to share these weapons with other countries in the Alliance. It is estimated that 20 American nuclear bombs are on Turkish soil – under the guardianship of the American army. This is perhaps the greatest asset in Turkey’s hands, in terms of military respectability. On the other hand, Turkey is still officially an aspiring member of the European Union – even though today this candidacy can no longer be taken seriously and the chances of an EU accession diminish more and more with the passage of time. These arrangements were made well before Erdoğan came to power.

The Turkey of today is multifaceted and does not see its north in the West. The current Turkish ruler has a close relationship, for example, with Russian President Vladimir Putin. This fact coupled with his NATO membership status means that Erdoğan’s actions are always on the radar of Western countries, especially after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the start of the War in Ukraine in 2022. Moreover, as already pointed out in an article in Foreign Affairs (open), Turkey has been getting closer and closer to other Middle Eastern countries, aiming to increase its influence in the region. In line with his Islamist and anti-Islamist ideology, Erdoğan has already shown his support for the Muslim Brotherhood and associated Islamists in several Arab uprisings in countries of the region.

Turkey also has its own agenda in Syria, especially because of the Kurdish presence in the north-east of the country. Since the 1980s, Turkey has had a policy of “forced assimilation” of Kurdish people into Turkish society, which in practice involves a ban on Kurdish language and customs. With the civil war in the neighbouring country, Turkey has used the lack of border control to advance its anti-Kurdish agenda in Syria. In 2019, after then US President Trump ordered the withdrawal of US soldiers from Syria who were supporting Kurdish allies, Erdoğan’s government began an air raid on border towns. Ankara considers the Kurdish organisation “Kurdistan Workers’ Party” (PKK) a terrorist organisation and has aimed to “expel” them from the region.

Also, because of its border position with Syria and the European Union, Erdoğan was in the privileged position of forcing the EU to negotiate, on its terms, agreements to “stem” the flow of refugees fleeing the Syrian Civil War into EU countries-following the so-called “Refugee Crisis” in 2015. Even after an agreement between Ankara and Brussels that set aid of billions of euros for Turkey to keep refugees on its soil, Erdoğan’s government decided to open its borders with Greece and even send several migrants by bus to the neighbouring country, creating tensions on the border³. The Turkish president knows how to use his country’s geography as a trump card in his hand.

More recently, after Russia invaded more parts of Ukraine in 2022, Erdoğan saw a new chance to exert power over some other European countries. With the negotiations for Sweden and Finland’s entry into NATO, Turkey showed that it would not give its assent for the countries to become members of the Alliance-not without giving in on several points of Ankara’s interest. Especially Sweden, which remains vetoed from NATO thanks to Turkey, is being “punished” for having condemned the Erdoğan government for human rights abuses and its policy of degrading democracy in its country. Protests in Stockholm in which the Koran was burned and an image of Erdoğan was hung upside down have further diminished Ankara’s willingness to allow the Scandinavian country to join the Alliance.

For these reasons alone, in this year’s elections, Western countries looked favourably on an opposition victory, or rather a brake on the direction Ankara has been taking under Erdoğan.

It is valid to look at some indicators to understand how Erdoğan has changed Turkey. Let’s start with the country’s economy. Turkey’s GDP has seen a considerable jump since the former mayor of Istanbul came to office in 2003. The country has gone from around $240 bn. in 2002 to a peak of $957 bn. in 2013, an increase of almost 300%–single exception to growth being the 2009 crisis. The increase in GDP per capita, the amount of domestic product divided by population, also grew to its peak in 2013, showing a minor growth of about 166%. In terms of world ranking, however, the Turkish economy only moved from 18th to 17th position among the world’s economies.

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

However, as the graph clearly shows, there were consecutive falls after 2013. The fall in Turkish GDP reached a maximum in 2020, accumulating a loss of almost 25% in value of its domestic product. But what was there to stop what looked like a successful policy of the AKP government?

In May 2013, protests broke out in Istanbul, initially intended to challenge plans to turn a small city park into a shopping mall. The protests, however, grew and spread across the country. Soon, the agenda also changed. Issues such as freedom of the press, democracy and the erosion of secularism caused by Erdoğan’s government became central to the protesters. The media’s neglect of the protests and the police violence against protesters made the movements grow even larger. Erdoğan especially blames these protests for the economic losses that the country has experienced since 2013¹¹. The fact is that the economic indicators started to plummet after that time.

Source: World Bank

Source: Trading Economics

When Erdoğan first took office in 2003, Turkey faced high inflation. World Bank data show that in 2000 annual inflation in the country was over 50%. By the year the AKP came to power, inflation had fallen to 45%. The average inflation rate in Turkey during successive Erdoğan governments was 9.2 percent until 2016, which remains high in global comparison, but well below the 50 percent of before. From then on, however, inflation spiralled out of control, reaching 16.3% annually in 2018. Close to the 20% mark again, as at the time when Erdoğan first took over the country, the government’s control seems to have disappeared.

The effects of the out-of-control economy also show in the exchange rate of the Turkish lira, the national currency. Having always remained below the conversion rate of two liras per US dollar before 2013, the Turkish currency began to depreciate slowly, reaching almost 4 liras per dollar in 2018. From then on, however, the currency began to lose even more value surpassing 7 liras per dollar in 2021, 13 in 2022 and, in May this year, reaching the maximum exchange rate of 20 liras per dollar, a devaluation of more than 1,000% since Erdoğan took office in 2003.

Finally, the social effects of the AKP government can be visualised with some indices as well. Starting with the Human Development Index (HDI), published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which gives scores considering life expectancy, education and per capita income, for example. On this scale, “1.000” is the highest score and means that the region analysed has a high human development. On the other side, “0.000” would mean the exact opposite. Considering this metric, the Erdoğan government has raised the standard of living in Turkey. At the beginning of his government in 2003, the country scored 0.690 on HDI, which is considered to be an “average” level. This index steadily rose until 2019, peaking at 0.842, which is considered “very high”. By 2021, the latest available data, the level had fallen a little, but was still in the same category.

Source: UN

On the other hand, the GINI Index, which measures inequality in a country, has undergone some interesting changes. Here, “100” represents maximum inequality, while “0” represents the ideal of no inequality. The AKP government took over Turkey with an inequality level in the region of 40 points, which is considered moderately high. In his first years at the head of government, Erdoğan managed to bring the numbers down to the 30-point range, indicating a drop in inequality in the country. This positive change, however, was temporary. Data shows that from 2010 onwards, inequality rose again, reaching levels higher or similar to those before the AKP came to power.

Source: World Bank

Finally, to analyse the state of democracy in the country, we bring data from the V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) database, especially the analysis of the “Liberal Democracy Index”. The index is based on the definition of the principle of liberal democracy that “emphasises the importance of protecting individual and minority rights against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority”. A higher level on this scale is achieved by “constitutionally protected civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances that together limit the exercise of executive power”, as is explained on the database page (open). Here we have a scale ranging from “1”, the highest possible level, to “0”, the lowest possible level. For levels of comparison, a high scoring country like Sweden averaged 0.88 over the last 20 years, while another low scoring country like North Korea scored 0.01. Here, AKP-led Turkey has fallen steadily on this metric, dropping from a median position of 0.52 points in 2003 to a low of 0.10. This index shows that Erdoğan’s Turkey has become a more authoritarian country, with a democratic regime that has been getting worse every year.

Source: V-Dem

With his victory confirmed, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has confirmed that he will be at the head of the Turkish presidency for the next five years, until 2028. The results of this election alone have a message about the interest Turks have in their president. As much as he has won the election again and remains undefeated in office, this is the first time that the opposition has come so close to removing him from office. This time, the election had to go to a second round, unlike his previous first-round victories. Holding back the public machine, however, guaranteed him victory once again.

The campaign saw several cases that benefited the AKP candidate to the detriment of the opposition. In the first and second rounds, for example, the Turkish president distributed money to people in his polling station and on the street. The opposition also denounced voting irregularities in the first round, although it acknowledged that they might not change the final result of the election²². The opposition candidate, Kılıçdaroğlu, acknowledged the loss, but said this was “the most unfair election in years”³³.

Source: Twitter (@AmichaiStein1).

What can now be expected is that Erdoğan, armed with his fifth election victory, will feel empowered to continue his quest to increase Islamic influence in the country by further eroding Turkey’s secular system. The way the election was carried out also gives no reason to believe that the democratic state in Turkey will improve, as the state machine was used heavily in the president’s favour. The head of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) observer mission reported that “public broadcasters clearly favoured the ruling parties and candidates” and that “most private TV channels (…) were also clearly biased towards the governing parties in their coverage”¹¹¹. An example of this can be seen in the image below of a channel belonging to Turkey’s second-largest media conglomerate:

For the West, Erdoğan’s victory means the continuation of an increasingly unreliable relationship and the expectation that whenever there is an opportunity for diplomatic blackmail, whether by the political use of migrant flows, or by vetoing action in NATO, or even by acting dubiously alongside Russia, Ankara will not think twice before putting other countries on the spot.

¹ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7482793.stm

² http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/7533414.stm

³ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-51735715

¹¹ https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/06/turkeys-erdogan-pins-economic-crisis-2013-gezi-protests

²² https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkey-opposition-says-irregularities-thousands-ballot-boxes-2023-05-17/

³³ https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/erdogan-positioned-extend-rule-turkey-runoff-election-2023-05-27/

¹¹¹ https://www.ft.com/content/7051e46f-5744-40aa-85af-d54b0d0878f1